The Legacy of Isiah Thomas

“That type of emotion, that type of feeling, when you’re playing like that, and you know, you’re really going for it…you’re going for it. You put your heart, your soul, you put everything into it, and…to know that all we went through as a team, and the people, and the friendships and everything…you wouldn’t understand”, said Isiah Lord Thomas, his eyes tearing up on television.

He had just watched a tape (for the first time) of the 1988 NBA Finals Game 6 between the Detroit Pistons and the ‘Showtime’ LA Lakers. The Pistons were up against a team with Magic in his prime, a team that had made it to the Finals seven times at that point in the decade. And the Pistons led the series 3-2, one game away from the franchise’s first ever championship. Isiah Thomas – among the most vilified basketball players in history – was tantalizingly close to having it all. It’s a two point game in the third quarter and the LA Forum crowd is growing nervous. And then, out on the fast break, Isiah charges into a Lakers player and crumbles to the floor clutching his ankle in agony. This is where any story of Isiah Thomas – NBA superstar, coach, executive, Public Enemy – must begin, although the real beginning was perhaps nearly half a century before.

During the first half of the 20th century, a majority of African-Americans migrated from the Southern states of the U.S. to Northern and Northwestern states in what is today referred to as the Great Black Migration. After the Civil War in 1865, it had become clear that Northern states were more hospitable to the African-American peoples than states in the hostile South, where they faced lynching, schools refused to enroll their children and jobs were scarce. Isiah Thomas and Mary Thomas were both part of this giant demographic shift in America; they moved from Mississippi to Chicago, Illinois in the first half of the 20th century.

The Great Migration concentrated manpower in cities, leading to the continued impoverishment of most families. The formation of ghettoes – urban housing projects for the poor, often migrant communities – followed from this. Isiah and Mary Thomas had nine children, the youngest of whom was named Isiah Lord Thomas. In his autobiography, Isiah writes that his father, a deeply proud man, despised basketball; he regarded it as a legacy of slavery. Basketball as a game where black people performed for the entertainment of white people. Accordingly, the Thomas household would not watch or play basketball.

Young Isiah’s father left the family when he was six.

What was in many ways a heavy financial loss was also a significant emotional gain. Isiah’s father had become abusive and rigid. Mary Thomas did not have the same expectations of her children. They were to do what they liked but they were to be the best at it. Stand up and fight for what you believe in, she said, and she knew perfectly well how much they would have to fight, having raised nine kids in the projects by herself.

Isiah’s skills on the basketball court started to become more and more pronounced. Luckily, Isiah grew up just at the time that school basketball in the US had become organized; an elite school for upper middle-class white kids, St. Joseph’s, offered Isiah a high school scholarship to play ball.

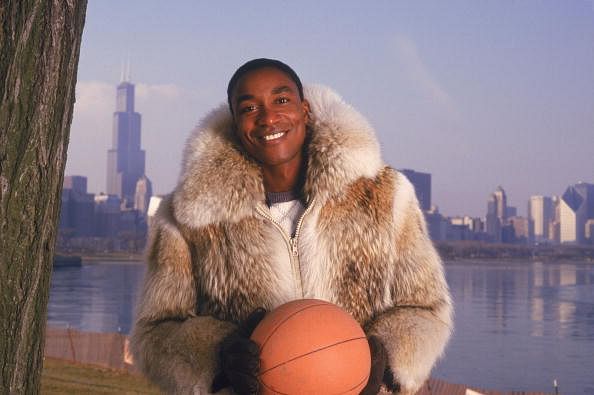

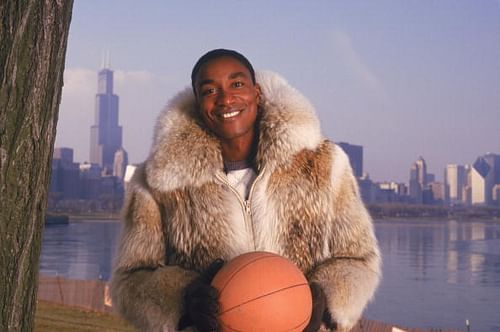

Today, Isiah is the epitome of cultured: soft, slow and articulate, not given to slang or colloquialisms. His winning smile makes him all the more ironic a figure for his critics to hack apart. He wasn’t always this way though; growing up so poor, he recollects “times we couldn’t eat”. “I wouldn’t trade anything for those days now”, a young Isiah told Sports Illustrated in 1981,”You learned to take care of your shoes, you learned to take care of your shirt”. Now he wears nothing but expensive suits and was at the helm of the highest paid basketball roster in the history of the game (the Knicks during Isiah’s tenure as GM/coach). To get from his home in the projects to St. Joseph’s, Isiah needed to start at 5 a.m., take three buses, each to the end of their lines and then walk a mile, often in the bitter Chicago cold. It took him over an hour and a half every day. At school, he was often the victim of hazing by white kids, who would chase him on their car as he walked to school.

At St. Joseph’s, he started to lose his street accent and diction – as his brother said derisively, he started to “talk white” (Slate.com, 2006). His confusing, often strained relationship with the white fans of the NBA probably started from this; a defiance coupled by a need to belong. Isiah once famously said Larry Bird would be “just another good player” were he not white-skinned.

His role on the team at St. Joseph’s got him nation-wide recognition. He was heavily recruited to play college ball and opted to do so at Indiana University under Bob Knight, among the most storied, prestigious and controversial college programs in the country. At Indiana, he picked up his most definitive nickname – at 6 feet, 1 inch, he was ‘PeeWee’, not ‘Magic’ like the other high school superstar of his age. He led the Hoosiers to the NCAA title in his sophomore (second) year before opting for the NBA Draft, where the Detroit Pistons selected him second overall. Isiah Lord Thomas, all puny six-feet-and-some of him, had finally arrived in the NBA.

A visibly hurt Isiah limped to the bench, his ankle badly sprained. The Lakers quickly seized control of the third quarter and opened up a lead. With about five minutes to go, Isiah, who is in all worlds of pain, limps to Coach Chuck Daly and asks to get back in. You have to be the best, you have to fight for it, Mary Thomas had said, and Isiah was not going to back down when his entire family had fought throughout their lives. What followed in that third quarter is now firmly in the ‘Legendary’ section of NBA Finals lore. He scored 14 straight points, on an assortment of bank shots, three pointers, twisting lay-ups while hobbling throughout. He had 25 points for the quarter, an NBA Finals record, and 43 for the game. He even got the Pistons the lead. In perhaps the most tragic finish to a playoff game, the Lakers prevailed in the final minute, with Kareem sinking two free throws from a questionable foul call on Bill Laimbeer. Isiah was a fraction of his usual self in game 7, struggling to stay on the court. The Lakers won the series 4-3. It wrenched the team apart. We wouldn’t understand how much it hurts, Isiah tells us. We wouldn’t. “I mean, we weren’t the Lakers, we weren’t the Celtics, we were just, we were nobody. We were the Detroit Pistons, trying to make our way through the league, trying to fight and earn some turf, you know, and make people realize that we were a good team”.

Zeke, as he is popularly called, started his NBA career with a bang, averaging 17ppg, 8apg and 2spg during his rookie season. In his second season, he was named an All Star game starter. The degree to which he took competition seriously was perhaps matched only by Jordan. Isiah always played with a chip on his shoulder; black guy, short guy, don’t need no respect, player for the Detroit Pistons. That Isiah played at the level he did was incredible; NBA point guards were much bigger and taller back then, and the game more physical. But PeeWee never backed away from a challenge.

By 1988, however, Isiah had found just the personality that fit him. He was a “Bad Boy” Piston for life. Hick, villain, hater, he played against both his opposition and the fans of every other franchise, the white guys he was looking to earn respect from.

The Pistons fortified their team-first identity with the next season (1988-89) and went on to win the NBA championship. They repeated the year after that; Isiah won Finals MVP. In those three seasons, Detroit shut down Jordan in his prime. The only legitimate star on those Pistons teams was Isiah.

Some would say that the legacy of Isiah Thomas the player is not as big as it deserves to be. What AI did for basketball, Isiah did in a decade where a short player like that had grocery lists of trouble every game. The move to draft Isiah no. 2 in 1981 Draft was criticized by every fan and columnist back then. You needed height to win at basketball. Isiah’s career averages – 19ppg, 9apg and 2spg – are great, but they don’t tell the whole story. He was the motor of the Bad Boy Pistons, he was what made them click. Above all, he was a selfless teammate. The Pistons won over 55% of their game for nearly a decade riding the Isiah wave. His legacy today is not what it should be, according to Simmons in The Book of Basketball, because today we place too much emphasis on stats. But basketball is not a game completely captured by statistics. There is the greatness from 1988, Game 5, to attest to that.

Over the last two decades, Isiah has done everything. He has run a storied NBA franchise – the Knicks – to the ground and summoned a decade of pain upon every Knicks fan. A sexual harassment suit (of which he was found guilty), bitter feuds with other basketball legends (Larry Brown, MJ) mark his professional career. He famously orchestrated the MJ “Freeze-Out” in the 1985 All Star game, where East players refusing to pass MJ the ball. Why? Because Isiah was feeling disrespected by the amount of attention MJ had garnered. Today, he has antagonized his fans, supporters, pretty much everybody in the basketball universe. Isiah Thomas is the longest running joke on basketball columns and NBA team management.

But the truth is in Isiah’s eyes at the end of Game 5. The anguish, the tears and the determination. The knowledge that he had to fight some more to get what was his. The truth is the six foot kid from the slums of Chicago is already a winner and a champion; nothing can take that away from him.