Connie Hawkins: Deprived, denied but not defeated

“Dreams of innocence are just that; they usually depend on a denial of reality that can be its own form of hubris.”

Oblivious to this reality, we are taught to believe, to be idealists, and most importantly, to preserve and nurture the innocence that comes along with it. We grow up believing that Santa is real, that meteors blazing across the sky are there to fulfill our dreams. But to a certain kid from the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn, New York, dreams were a luxury that he wasn’t supposed to have.

Was it because it was too much of an overbearing thought? Was he looking to go beyond the realms of rational and pragmatic thinking into domains unchallenged and unconquered?

Well, no! He wished to play a game that he loved beyond anything else in the world, and wished to play it with the best players in front of the biggest crowds. His dream was innocent indeed, and could’ve been cast off as being slightly unrealistic. But even before he had harboured enough fantasies, his dream was stolen from him and he was cast into a stark, inexorable and intransigent world where he was judged and discriminated on parameters that he neither understood nor realized.

Connie Hawkins, the man who was denied a right to dream.

Hawkins was born on July 17, 1942 at a time when the sport of basketball was still in its nascent stages. The NBA then was a distant dream as the game’s future tethered between the uncertainties and the vigorous harmonics of the BBA, the ABL and the NBL.

But in the hamlets and ghettos of Brooklyn, the game of basketball was beyond the glitz and glamour of a professional league. Cast amidst the world of drugs, poverty, teenage-crimes and other such opprobrious shenanigans, basketball was maybe their only pure and holistic adventure.

And it is this back-drop that defines the life and the struggles of Hawkins. Poverty-stricken and malnourished as a kid, his growing up days were far from rosy. Not the smartest kid around, Connie had an IQ of 70, and a not-so-surprising disdain for books. The only thing that he loved was playing basketball, a sport in which he had developed an excellent reputation. He could do manoeuvres that belied his age, and with such moves came the obvious respect from the boroughs. So much so that a few philanthropic people paid his school fees so that he could feature for the local Boys High school team. Connie starred as a basketball player, averaging over 25 ppg, and under the weight of such amazing displays, his grades were morphed. The school and the people in the boroughs encouraged Connie to lay low on his academic liabilities and concentrate on basketball. Connie saw no harm, as basketball got him respect, earned him favours and made him a celebrity.

Connie’s reputation wasn’t limited to the courts of Brooklyn, and soon almost every college in the country had started to show interest in him. Connie had grown into an all-round player, who many believed could change the very face of the game itself. Standing 6’8”, he had remarkable dribbling ability and a perimeter game to go along with his gravity-defying dunks, an expansive repertoire of post-moves and an awe-inspiring ability to palm the basketball with one hand, all the while moving with utmost grace. By Connie’s own admission, he aimed to break the laws of gravity, famously stating, “Someone said if I didn’t break them, I was slow to obey them.”

Connie’s reputation wasn’t limited to the courts of Brooklyn, and soon almost every college in the country had started to show interest in him. Connie had grown into an all-round player, who many believed could change the very face of the game itself. Standing 6’8”, he had remarkable dribbling ability and a perimeter game to go along with his gravity-defying dunks, an expansive repertoire of post-moves and an awe-inspiring ability to palm the basketball with one hand, all the while moving with utmost grace. By Connie’s own admission, he aimed to break the laws of gravity, famously stating, “Someone said if I didn’t break them, I was slow to obey them.”

Connie joined Iowa State University, and his reputation meant he was always the centre of attraction. He found favors easy to come by, and candidly took them for granted. Be it alcohol or cigarettes, Connie had started to do it all. Maybe the culture was playing on him, but he was christened as a legend, and he believed that he owed it to his supporters. It was at this juncture that he met Jack Molinas, the infamous New York attorney who was at the centre of one of the biggest point-shaving scandals in the history of college basketball.

Hawkins had befriended Molinas because he knew him as a playground hero, and found a common interest in basketball. His only sin was maybe that he accepted a loan of $200 from Molinas, a sum that he promised to return. When the whole point-shaving scandal came to the fore, Connie’s name was also dragged along because of his supposed friendship with Molinas. Hawkins was still a freshman then, and in those days freshmen weren’t allowed to play in the NCAA. So Hawkins certainly could not have been a direct perpetrator of the crime. He was accused of being a middle-man, someone who introduced Molinas to the players.

Hawkins pleaded innocence, but he was never the most confident kid and his modest education hadn’t prepared him for anything like this. He was kept from seeking legal counsel, a right that he didn’t know he could exercise. On being grilled by the blustering detectives, Hawkins got scared and in order to mollify the grilling, and unable to endure the pressure, he accepted things that he never did without realizing its implications. He was just a very scared 17-year old who didn’t want to go to jail, and despite being clean, didn’t know how to convince the hectoring detectives.

Hawkins wasn’t charged due to lack of evidence, but the damage was done. The prejudiced and libelous, even racist attitude of the authorities didn’t help his cause as he was blackballed from the NBA and expelled from Iowa. To the league, he was just another black kid who had gone rogue and was nothing but a nuisance that they were more than happy to keep at bay.

Hawkins was watching his whole world crumble and looked for a reprieve under the lesser known ABL. Even before he could find a hint of stabilization and normalcy though, he would face another disaster. Within a year of his joining the ABL was scrapped, and all the uncertainties returned. The tunnel was dark again, and Hawkins was slowly losing all trace of light. He needed a job, and when the Harlem Globetrotters came calling, he agreed to it without a thought. He needed a break, and the Globetrotters gave him just that: a chance to entertain, to feel good about himself and to earn his living performing burlesque routines.

His time with the Globetrotters reinvigorated his passion for the game, as in between the amazing acts, he had learnt his greatest ability and strength. It was to entertain, and he loved nothing more than drawing the awe of the crowd. He found motivation again, and filed a $6 million lawsuit against the NBA, claiming the league had unfairly banned him from participation despite him being acquitted of all charges. He also decided to give professional basketball another shot, and with a far more mature and determined head on his able shoulders, he stood ready for the renaissance.

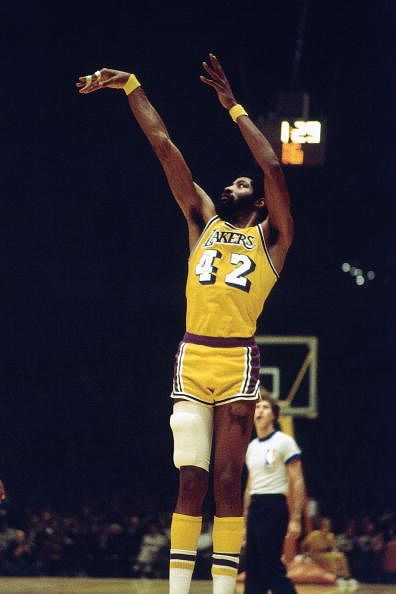

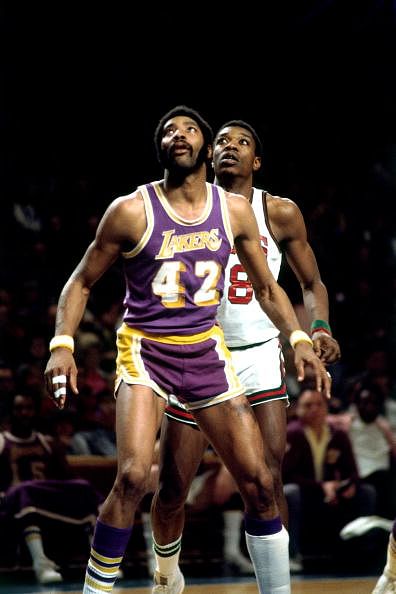

Hawkins joined the Pittsburgh Pipers in the inaugural 1967–68 season of the ABA and led the team to the Championship, winning both the regular-season and play-off MVP awards. His exploits with the ABA did his case a lot of good and justice was rightly served when the NBA settled the case with a cash agreement of $1.3 million, allowing Hawkins to join the Phoenix Suns. Life had come full circle for the dreamy and acquiescent kid, who had seasoned into a mature and astute individual. His life lessons had been tough, and may have stolen away his shot at having a gargantuan legacy, but Hawkins chose to remain positive, stating “I was so happy to play, I didn’t have any problems with animosity or bitterness at all. As soon as I got that Phoenix Suns uniform, I just wanted to play.”

Hawkins joined the Pittsburgh Pipers in the inaugural 1967–68 season of the ABA and led the team to the Championship, winning both the regular-season and play-off MVP awards. His exploits with the ABA did his case a lot of good and justice was rightly served when the NBA settled the case with a cash agreement of $1.3 million, allowing Hawkins to join the Phoenix Suns. Life had come full circle for the dreamy and acquiescent kid, who had seasoned into a mature and astute individual. His life lessons had been tough, and may have stolen away his shot at having a gargantuan legacy, but Hawkins chose to remain positive, stating “I was so happy to play, I didn’t have any problems with animosity or bitterness at all. As soon as I got that Phoenix Suns uniform, I just wanted to play.”

Hawkins’ introduction into the league is maybe the greatest story of vindication in all of sports. He averaged over 24 ppg, 7rpg and 5 assists, en route to being named an All-Star in his first season with the Suns. His greatest achievement came when he burned the mighty Lakers boasting of the likes of Wilt, West and Elgin for 34 points, 20 rebounds and 7 assists to a memorable win in game-2 of the Western Conference Play-offs. The game showed the world what the league and the basketball fraternity had been deprived of.

His next few years in the league were rather subdued as he battled injuries, and he retired in the year 1976. When he was inducted into the Hall-of-fame, Hawkins stated, “After I realized what the call was about, I cried. I think maybe I’ve grown an inch or two this past week.”

Yes, indeed. He did grow beyond many daunting obstacles, and his irrepressible attitude has left us a legacy that shall always shine above the deepest trenches of poverty, illiteracy, greed and racism. And he did all that by fighting, rather than sitting and crying foul. A playground legend, who remains a shining example of what to do on court, and what to avoid off it.

As Larry Brown famously said, “He was Julius before Julius. He was Elgin before Elgin. He was Michael before Michael. He was simply the greatest individual player I have ever seen.”