"It’s a little jarring": Andy Bernstein on capturing the In-Season Tournament, working with Kobe on his book, and more (Exclusive)

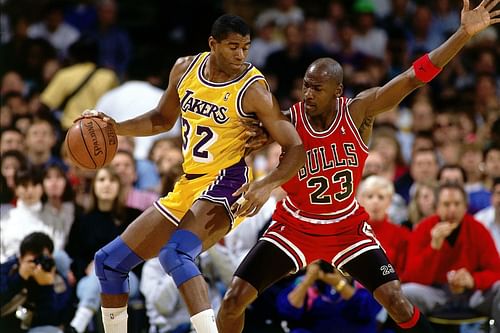

Instead of looking at the photo in admiration or nostalgia, Kobe Bryant examined Andy Bernstein’s photo of Michael Jordan with a critical eye.

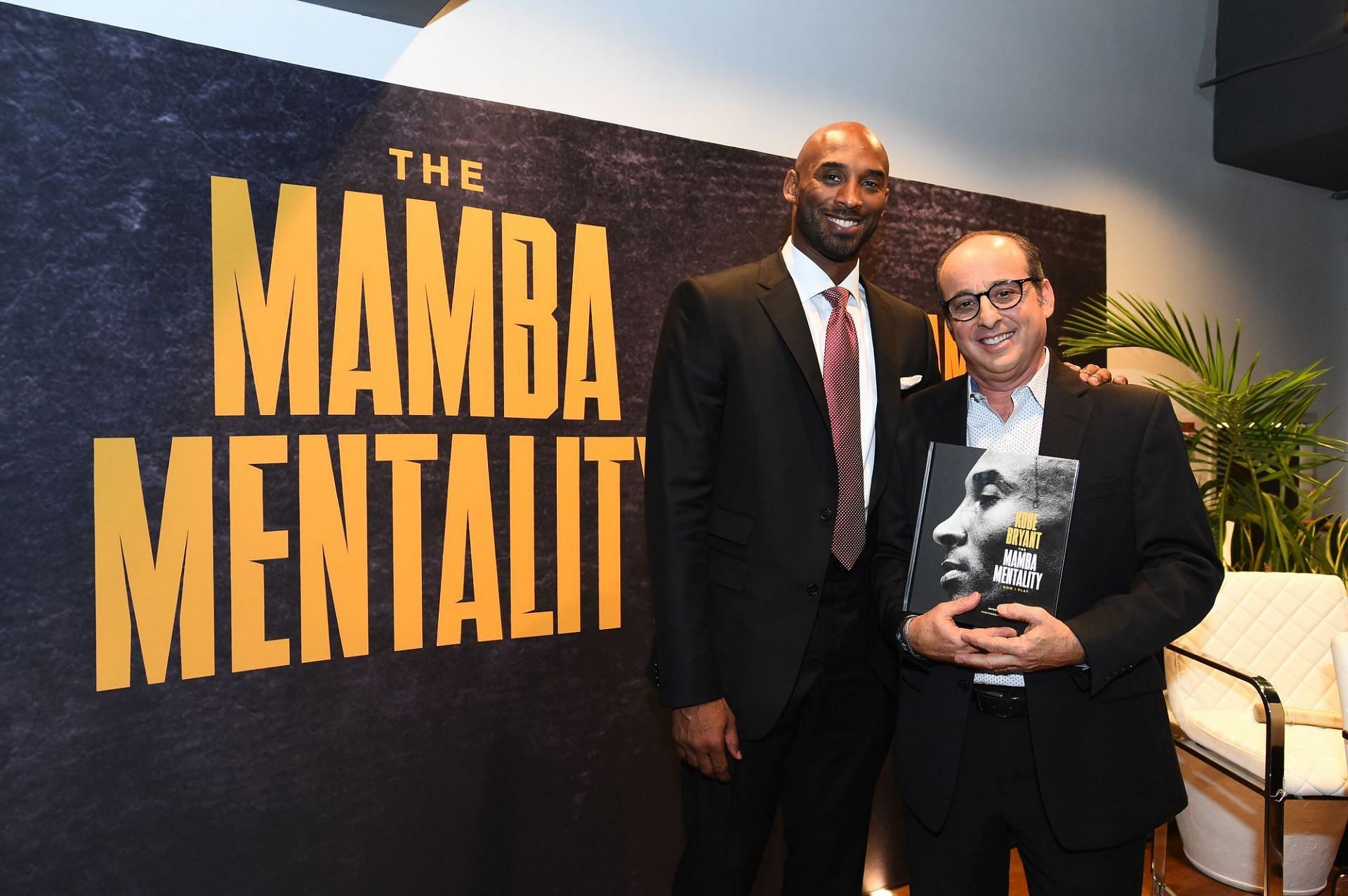

In a photo that Bernstein captured of Bryant during his second season with the Los Angeles Lakers (1997-98), Bryant did not like his posture and balance while defending Jordan during his final season with the Chicago Bulls. When Bryant worked with Bernstein, the NBA’s long-time senior photographer, on his coffee table book filled with analysis of his craft (“The Mamba Mentality”), Bryant instructed Bernstein to include that photo so he could outline his detailed critiques.

“Who does that in their own book?” Bernstein said, laughing. “That was very self-deprecating and very revealing about him about how he was always trying to improve. He’s pointing out to the reader, whether it's a coach, player, or a general fan, that, ‘Even I did stuff wrong; that’s how I learned.’ I loved that.”

Bernstein detailed to Sportskeeda what it was like to shoot photos of various NBA stars, including Bryant, Jordan, Magic Johnson, Larry Bird, and LeBron James. Bernstein shared what it was like to collaborate with Bryant on his coffee-table book. And Bernstein offered insight into what went into shooting various memorable photos, including of the Lakers-Celtics rivalry in the 1980s and when James eclipsed Kareem Abdul-Jabbar as the NBA’s all-time leading scorer.

Editor’s note: The following 1-on-1 conversation has been condensed and edited

How do you compare what it was like to shoot photos of Magic, Larry, MJ, Kobe, and LeBron?

Bernstein: “It’s always a learning process for me. I had to learn these guys’ games. I remember early in my career shooting Magic, you have to keep in mind that I can only take one photo every four seconds. I can’t shoot a motor-drive sequence because of the strobes that we have in the arena that have to be recharged. I had to shoot one photo, wait for four seconds, and then shoot another photo because the flash system had to recharge itself back up. You can’t shoot motor drive. If you shot in between while the recycling period was going, you would blow the strobes out. With Magic, it was frustrating.

Magic is coming down the court toward me at full steam ahead and he’s looking at 12 different directions. He’s got [James] Worthy on one side, [Michael] Cooper on the other, and Byron [Scott], too. I don’t know what he’s going to do (laughs). Many many times, I guessed wrong. Then I kind of sort of started to figure him out. I don’t know if it was from experience. But I saw what he was going to do. That’s in contrast to Kareem. He was so predictable. Kareem would get the ball. He would bounce it a couple of times and do the skyhook. The skyhook was very methodical. You knew when exactly to shoot it at the pinnacle of the motion.

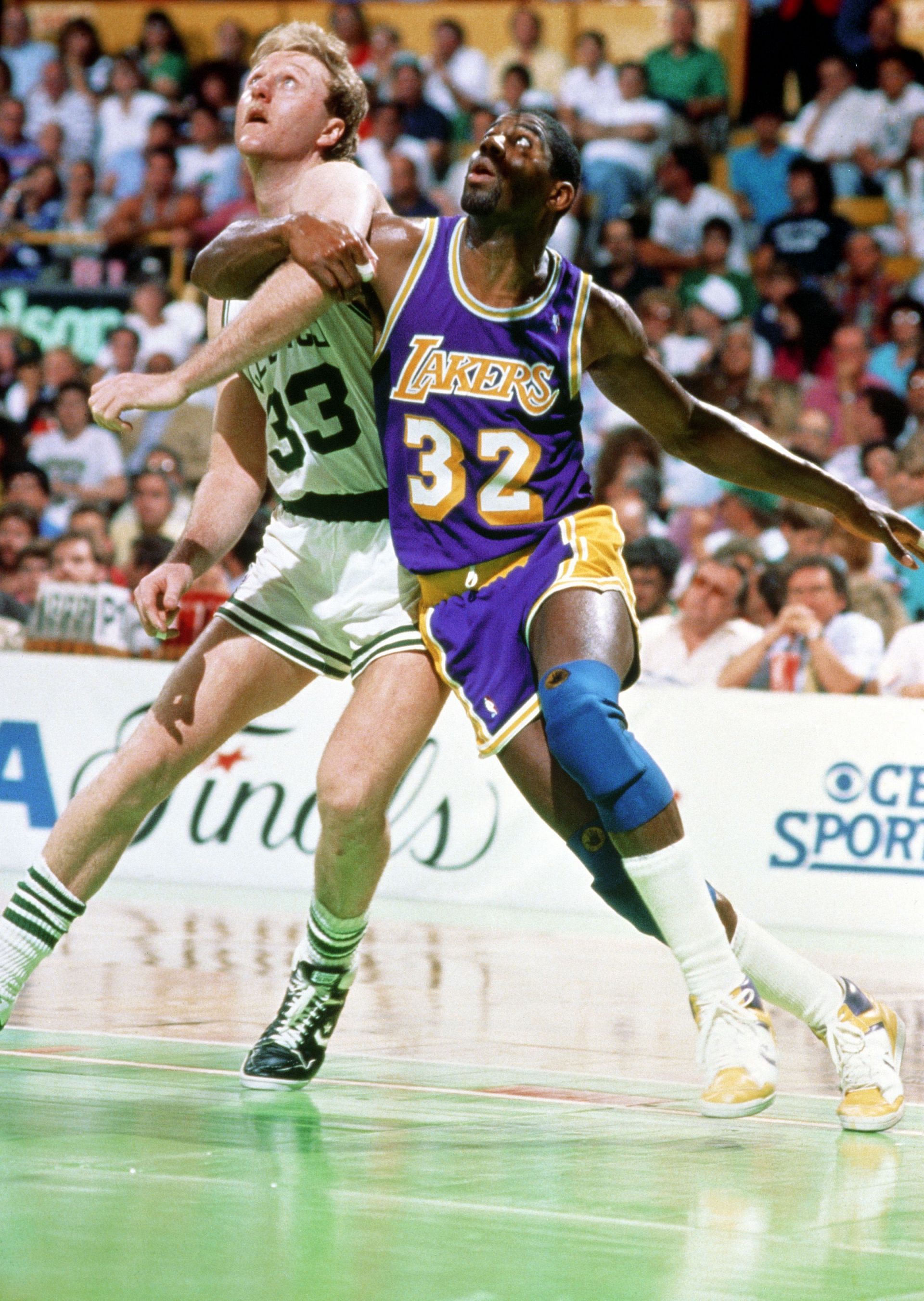

Michael was a whole other story. Michael was all over the place. He was incredibly athletic and could basically jump out of the gym. Michael had incredible facial expressions and reactions. Of course, early Michael dunked a lot. Larry was a whole other story because he was very flatfooted (laughs). He had so many nuances to his game. Then getting these guys in the same frame together with Magic and Bird was probably one of the hardest things that I had to do in my career. They never matched up against each other. In those days, guards and forwards didn’t really switch and cover each other. I had to be very patient and hope somehow that by some divine intervention, they would end up in the same frame together.

Michael and Magic were a different story because they actually did guard each other. Then we get to Shaq [Shaquille O’Neal], who is just a freight train. I wouldn’t say Shaq was predictable. But you knew at some point in time that he would go up and dunk. It was really just a matter of being patient with him. He was just an animal out there. You had guys draped all over him and go up and dunk. The picture is the moment before the moment of guys trying to pull him down or foul him. The ferocious dunks were great.

Then with Kobe, as you remember, a young Kobe was a dunk machine out there. Once he got to play and let the racehorse out of the gate, if I didn’t come back with four or five dunks a game regularly, that was a disappointing night. I had to learn his game. I was around him for 20 years and watched his game evolve. He became an incredibly lethal outside shooter. To me, that is a pleasure to watch a player’s game evolve and be able to document that. Then LeBron is a mix of everybody. As a photographer, I could put LeBron in each a bucket. A dunker, a shooter, an incredible passer, and great expressions on the court and interactions with teammates.

Those are all the stuff that I need to get. Plus, there were matchups. LeBron and Steph [Curry] had four Finals that they played against each other. Or LeBron vs. D-Wade [Dwyane Wade] and then playing with D-Wade [in Miami]. There were legendary moments of LeBron and Kobe together. Now we have [Victor] Wembanyama, who is completely different than any other guy that I’ve ever shot. He’s a little bit of a freak of nature to be that tall and have skills like he has. He is agile and has skills with being able to go between the legs and bringing the ball downcourt. The first points he had in the NBA was a 3-pointer, which I shot. He looks like a telephone pole, but with skills. It’s just amazing. Then there’s [Nikola] Jokic, and the insanity with his game. It’s a challenge every night to go out there and not see these guys before and then hone my game as I watch them develop their game. That’s one of the things I really love about what I do.”

When you worked with Kobe on “The Mamba Mentality” book you could see him through a new lens essentially on what he’s like as a teammate. What are your favorite stories that capture what that dynamic was like?

Bernstein: “Honestly, I couldn’t have asked for somebody better to collaborate with. As we all know, you know and I know, he was laser-focused on what he wanted. There was never a moment where he was waffling and said, ‘Maybe we should try this.’ It was ‘No, this is what we’re doing. We’re doing a book that will tell the world what ‘The Mamba Mentality’ means to me in my words, not as told to or anybody else’s interpretation. It’s my words and what the Black Mamba meant and why I took on that superhero kind of character. And you’re going to illustrate it, Andy, with your photos.’ (laughs). That was the end of the conversation. I was like, ‘Okay, let’s go!’

We kicked around ideas on how the book would be broken down. He wanted the book to be broken into two parts – process and craft. The process is everything that is involved with your preparation, injury recovery both mental and physical that goes into making him the elite athlete that he was. Then craft was everything basketball-related. Defense – how he sized up his opponents and the mental approach. In that section, he had specific players he played against and played with and also talked about Phil [Jackson]. The book was a first-person account of ‘The Black Mamba’ and what the ‘Mamba Mentality’ meant to him.

Working with him was a dream. Luckily, he had some great people on his team and his side that facilitated getting him to sit down and do the work that he needed to do for the book. On our side, I had great people working at NBA Photos back in New Jersey because half of his career happened pre-digital. So, it was all film that had to be researched and in the archives. It was a big job. But the end result was that we found 95% of the stuff that he had asked for. I’m very proud of that. I never had to go back to him and say, ‘I don’t have a photo to back up what you are saying.’ There were a couple of moments where there wasn’t the specific photo he was looking for because he had a photographic memory (laughs). But we could work around that. I’m super proud of the book, and the book is now part of his legacy in his words.”

What did you think of his revelation in the book that, after he first saw your photo of him guarding MJ, he then corrected his posture and balance?

Bernstein: (laughs). “Think about it. This is his own book, and the opening photo for that section is captioned, ‘Everything that I’m doing in this picture is wrong’ (laughs). Who does that in their own book? That was very self-deprecating and very revealing about him about how he was always trying to improve. He’s pointing out to the reader, whether it's a coach, player, or a general fan, ‘Even I did stuff wrong; that’s how I learned.’ I loved that. I loved that he was very open about his curiosity and non-stop relentlessness. He picked Michael’s brain constantly, but also other people in and out of sports that he admired. That’s one of the tenets of ‘The Mamba Mentality,’ which is curiosity. If he was never curious, he would’ve never called John Williams, the multi-Oscar-winning composer, and would’ve never had him score ‘Dear Basketball’ and won an Oscar. This is the kind of guy he was.”

You’ve said that your photo of Kobe when he’s icing his ankles and dipping his finger in cold water is one of your favorite photos. Why is that?

Bernstein: “The photo really speaks to his work ethic. The backstory on that is I was embedded with the team during the 2009-10 season and traveling with them. I was at all the home games and at a bunch of practices. Phil and I were working on the ‘Journey to the Ring’ book that season. We were on the “Grammy’s trip” where we were in nine or 10 cities in the middle of winter. The team had played the night before in Cleveland. He was banged up. Both of his ankles were a mess. He had a busted index finger on his shooting hand. They had played the night before, and I remember it was a late game because it was a network game. So we didn’t get to New York at our hotel until about 4 or 4:30 am. Then, Kobe has to play that same night less than 24 hours later in another city. Here we are at Madison Square Garden, and he is literally willing himself to play. The Garden didn’t have a private area where he could go to do his meditation and pre-game prep with his trainers and all of that. He was stuck in the main locker room. It’s a really small visitor’s locker room in the Garden.

So I’m doing what I do with being a fly on the wall. Through my last pass in the locker room, before they shut the door for private time with the team, I walked by him and looked to my left and saw him. I clicked two shots, and I just prayed that the sound of the shutter clicking wouldn’t disturb him. Of course, it wouldn’t because he’s in his own zone. To me, all of the elements come together. As a photographer, it’s a journalistic moment. But it’s also very revealing as to what kind of athlete this guy was and what goes on behind the scenes before he has to come out when the curtains are up. In my experience, nobody worked harder at preparing himself and recovering than he did.”

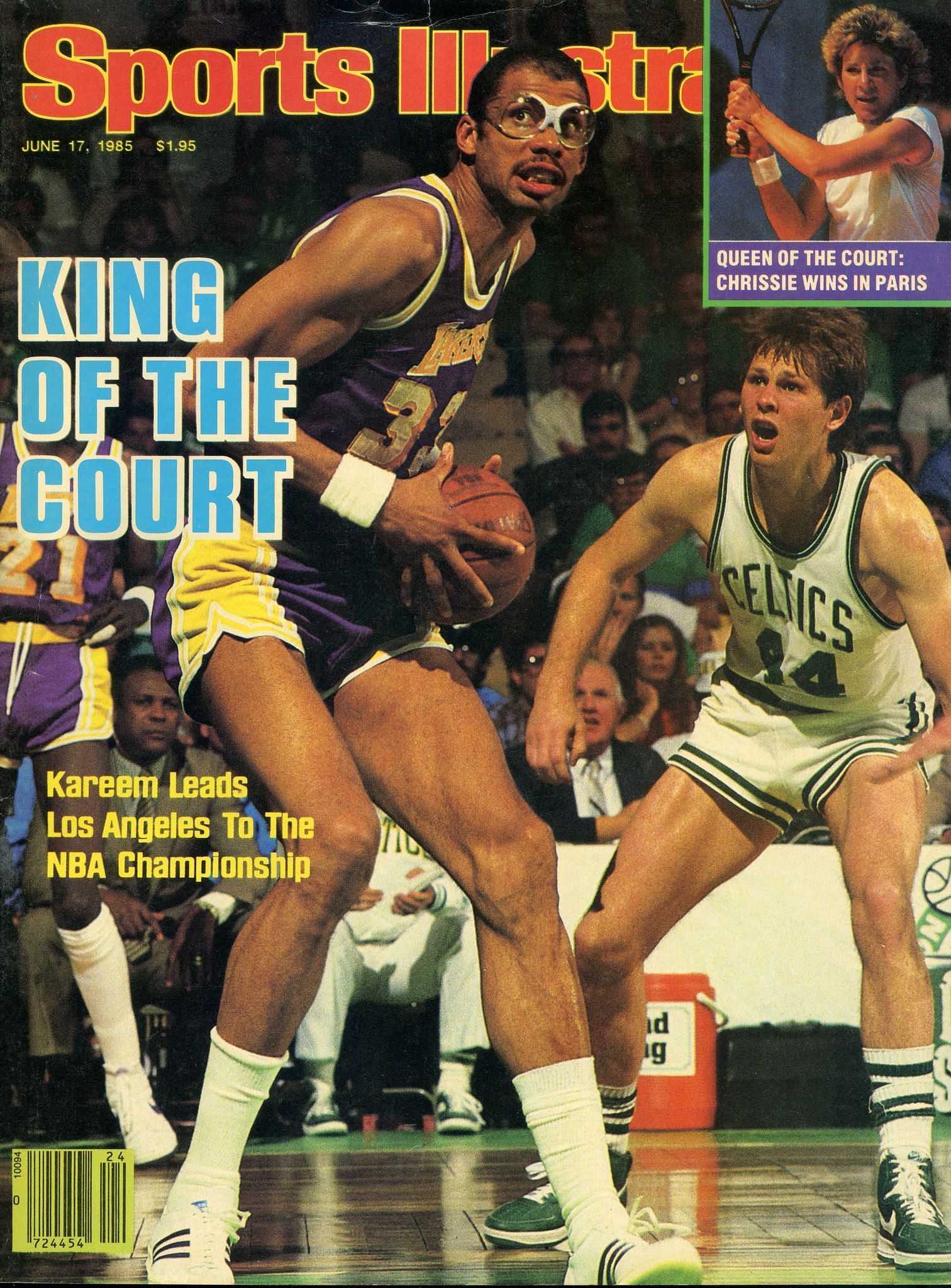

You have also told me and others before that you most enjoyed shooting the 1985 NBA Finals out of all of the Finals you covered. Why does that specific Lakers-Celtics matchup rank the highest?

Bernstein: “Historically, it was an incredible moment and an incredible feat. No Lakers team had ever beaten the Celtics, especially in the Garden. To finally have them get the leprechaun off of their back and come back in the Finals? Those Finals had “The Memorial Day Massacre” (Celtics beat Lakers in Game 1, 148-114). Everyone thought Kareem was washed up, and blah blah blah. It was also historic for me as a photographer. It was a benchmark experience for me because my first cover of Sports Illustrated came from that Finals. As a young sports photographer, I set these benchmarks for myself and these goals. Obviously, that was a very lofty goal to finally get on the cover of Sports Illustrated. Once you get that, you’re in with the big boys. If you only get one cover in your career, they can never take that away from you. It was a poignant and wonderful moment. It was very affirming for me to have worked at that point.

It was also an incredibly competitive series. The Lakers should’ve won the ’84 Finals, but they didn’t. Having me embedded with the team and seeing how much they wanted that series, it was reminiscent of 2010 with Kobe. He famously said he would never retire until he beat the Celtics in the Finals. It was kind of the same feeling in ’85. They needed to win that Finals to avenge the ’84 one. It was great. There were a lot of great moments. In terms of the Finals, you can find a moment or two from every single one of them. But that one sticks out at No. 1.”

What’s your favorite photo of Lakers-Celtics in the Finals that really captures the intensity of the rivalry?

Bernstein: “It has to be Magic and Bird being intertwined with each other during ’87 Finals. It was shot at the Garden. SI did a cover from that photo. They titled it ‘Memories’ and released it in ’92. It’s a really poignant photo because both guys are intertwined. Neither guy is dominant over the other. Not one guy is over the other one. It’s rare to get that one, too. Usually, one guy has position and one guy is more dominant. But it turned out that was the right moment in time. There were a couple in the two championships in 2008 and 2010. I had one of Kobe going against the Celtics in 2008. But the Kobe-KG matchups and Kareem-[Robert] Parish and Coop-Bird, you name it. Every time down the court was an incredible photo opportunity (laughs).

Fast forward to MJ’s last shot. What went into being prepared for that?

Bernstein: “That was an incredible team effort. We were at the infancy of developing this multi-camera system that could be fired with these radio remotes. They are very involved. Back then, it was a very intricate system where you could fire multiple cameras at the same time with the same strobe bursts going off in very strategic areas of the arena. They could be fixed remotes like the camera put through the backboard in an overhead position. We also used human remotes. People sat on the court in elevated positions. In those days, we had more photographers that could sit on the court. They were holding their own camera. So picture this. You’re sitting on the opposite end of the court from me and are holding your own camera and focusing since this the pre-auto-focus days. But I’m the one triggering and pushing the button on your camera. I’m doing it by a radio remote.

We had gotten burned before earlier in the Finals where there was a last-second shot, and a couple of us got blocked. We didn’t produce the photo that we should have. So our boss at the time, Carmin Romanelli, sat us all and said, ‘We need to have a protocol for a last-second shot opportunity for a tying shot or game-winning shot.’ The protocol was that if the last-second shot was on the opposite side of the court from where you’re sitting, then the requirement is you have to go wide, shoot horizontally, and go sideline to sideline with the basket and the 24-second clock in the photo. ‘Go wide and loose’ is what we were instructed to do.

To complicate it even more, Fernando Medina, one of our NBA photographers and one of our human remotes, was on the opposite side of me. I’m in the corner. Michael fakes [Byron] Russell. He goes down a little bit, and then I get blocked by either a referee or another player. I couldn’t see Michael for a split second after he made the fake. I’m on him and can see him and he goes up, and all I can see is the bottom of his feet. I knew that Fernando was the human remote. We had another guy, Scott Cunningham, up in the stands at the 50-yard line shooting the back of the scene as another human remote. So I knew if I couldn’t get it, they would get it. And they did. Both of them got the shot. There is one frame of the ball in the air at 0.6 [seconds left], and everybody is standing up. It’s one of the most iconic photos in NBA history.

The big discussion has always been, ‘Who gets credit for the photo? Does Andy get credit because he pushed the button at the right time? Or does Fernando get the credit because he literally shot it?’ Since day one, I’ve always held that Fernando gets the credit because he did his job. He had the camera positioned the right way. He framed it correctly. And it was focused. I pushed the button in the moment. But he deserves the credit for that. As a group, we all deserve credit because this was truly a group effort from NBA Photos that we replicated many times. Think of Ray Allen’s shot in the NBA Finals [2013 against San Antonio]. Think of Kyrie’s game-winning shot in Cleveland [vs Golden State in 2016]. Think of Kobe against Detroit [in 2004]. This has now become the standard. We don’t use human remotes anymore because we’re able to have remote cameras that can shoot from a fixed position. We also don’t have the luxury of having as many photographers on the court anymore.”

What was the setup that became key to capture LeBron’s dunk [in 2020] that looked eerily similar to Kobe’s?

Bernstein: “I’m not one of those that buys into ‘It was similar to Kobe’s’ theory. It was a little bit coincidental. It happened on the same basket in the same arena with sort of the same dunk. Unless I can actually ask LeBron one day, I can’t imagine at the moment that he thought he was going to do the same dunk as Kobe. You’ve seen the footage on it. It was so freaking quick when he took off and the ball was elevated at his hip. Then, he did the two-handed dunk. I’m on the other side. You can see me in the picture at the bottom next to the basket on the other end. It was a breakaway. I have to time it by watching him elevate but from the back. If I get it wrong? Remember, I only have one shot every four seconds. So the ball would’ve been in a bad position, whether it was in front of his face or his arms would’ve covered his face. It wouldn’t have worked. This was a millionth-of-a-second decision. So honestly, I got a little bit lucky on that.

I never have really seen LeBron or other players dunk after they had the ball down on their hips. Maybe Dominique [Wilkins], Vince Carter or Kobe. But they don’t usually do that. It worked out perfectly. With it happening right after Kobe’s death, it was tragically coincidental with everything in this picture. I know it meant a lot to LeBron and to the fans out there. It is eerie. One of the Lakers’ video guys [Josh Williams] put that footage together. It looks literally like a carbon copy. It is pretty cool. I like that photo.”

Similar question, but on capturing the moment LeBron broke Kareem’s all-time scoring record. How did you pull it off?

Bernstein: “The LeBron chase was just like when I was there for when Kareem was chasing Wilt [Chamberlain]. I don’t know how many media members were there both for when LeBron broke Kareem’s record and for when Kareem broke Wilt’s record. I may have been the only one. I’m not sure. But I was there when that happened. I chased LeBron for the last three or four games for when he was within striking distance. It worked better for me. He came into the game [vs Oklahoma City] needing 32 points. If it was going to happen that night, it was going to happen at some point in the second half on the other side of the court for me. That’s not ideal because a lot of things can go wrong there. You can get his back. He can be just shooting a free throw. Or he can go to the rim and get lost in traffic. There are a lot of photographic things that can go wrong. But it just happened to work out perfectly when he took that long step-back shot.

He was wide open between me and him. I was on the other side of the court. I’m going to shoot loose because I want to see the scene. What’s crazy about that picture is that every single person has their cell phone out (laughs). Every single person except [Nike co-founder] Phil Knight, who is sitting courtside, and two other guys. That speaks to a lot of things. People now want to be in the moment, but also record that they’re in the moment. They’re doing a selfie or shooting it to prove they have been there. That’s kind of funny. When Kareem broke Wilt’s record, nobody had a camera. Everybody is just watching it happen. But it was very gratifying to me. As Phil Jackson used to say about ‘full-circle career moments.’”

You’ve documented countless games in the playoffs and the NBA Finals, but what’s your thought process on how you shoot the In-Season tournament in Las Vegas since it’s a new setup?

Bernstein: “They present a few challenges. We’re locked into what we’re used to these days. When you go into Crypto.com Arena, I know what the Lakers court is going to look like and I know what the Clippers court is going to look like. The Lakers don’t ever change their court. The Clippers have a couple of different courts. It does affect exposure and some technical things. But we adjust for that. I had my first dose of that in San Antonio when I covered Wembanyama’s first In-Season tournament game and they had the court down. It’s a little jarring at first because you’re not used to seeing that and I’m kind of set in my ways. But it actually made for a really cool overhead angle. That made for some cool photos of that because of the way the court was painted. It was pretty interesting.

Mark Medina is an NBA insider for Sportskeeda. Follow him on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and Threads.