Grandmaster, chess commentator, writer, and Yale grad: In conversation with Robert Hess

Chess Grandmaster Robert Hess is a multi-talented individual. With a degree from Yale University, one of the eight Ivy-league universities, and amongst the best in the world, Hess has overcome great odds to succeed in a variety of ventures.

Not only has he won a medal at the Olympiad, secured the Samford Fellowship for the best American chess player, been the trainer for the US Women's Olympiad team, and a prominent commentator on chess events around the world, Robert has also interned with a finance firm.

He has also interned with Sports Illustrated as well as his own company called the Sports Quotient, amongst others. In order to ask him about his various ventures and interests, we set up an interview with the master. So, let's jump straight into the Q/A!

1. Let's go back in time and talk about your introduction to chess. How were you introduced to the game and what was your early experience like?

My dad taught me and my siblings how to play chess when I was around five. He played chess when he was in high school and, as a father of three sometimes rowdy kids, thought it'd be a good alternative to video games. For whatever reason, I was fascinated by the game.

Luckily, my school had a chess program and that is where I met the only coach I ever had - Grandmaster Miron Sher. Miron is a gem of a coach, and there are not enough words to describe the impact he made on my chess career and my life overall. I was privileged to have a family that supported my growth and had the financial means to provide me access to such excellent coaching and tournament experience.

2. When did you realise that chess was more than just a game/hobby for you?

In third grade (2001), I gained around 700 rating points and won the City, State, and National K-3 Championships. I became the top rated player in my age group in the United States (Fabiano Caruana, now the world's second-highest rated player, is 8 months younger than I am, and for a few years we'd be around the same strength). By then I'd long had a love for the game, but with that kind of ascent it was hard to ignore the possibilities.

3. You became a GM in 2009. Can you trace your journey to achieving this title?

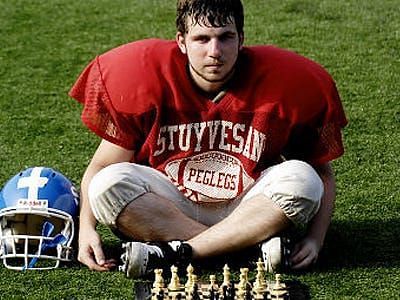

I earned the International Master (IM) title during my first year at Stuyvesant High School (2007). At that point in my life, I started to participate in fewer tournaments, both by choice and due to requirements. For starters, the workload at my school was quite intense, and free time was relatively limited. I was also a teenager who did not want to be singularly focused on chess; I was on the (American) football team for a couple of years at school and also enjoyed partaking in other extracurricular activities or just hanging out with friends.

And, back then, there weren't all that many higher level tournaments in the US. So that meant I either had to travel internationally or perform well at the American events I played in, which tend to have two games in a day (which can be north of 10 hours of gameplay) and little time to prepare between rounds.

Somehow, despite a very hectic junior year, I managed to score consecutive Grandmaster norms and earn the title in quick succession in March and April of 2009.

4. You even tied for second in the U.S. Championship and were awarded the Samford Fellowship. How were these experiences for you?

Finishing in second place in the 2009 U.S. Championship is my crowning achievement in terms of my own play. The tournament was just a month after I earned my final GM norm, and I was officially seeded 17th out of 24 participants. I think that helped me, as expectations were relatively low on my end.

The GMs I faced had more pressure on them; whereas a draw would be 'fine' for me, the onus was on my opponents to play a bit more riskily to score full points and compete for the title. I used this psychology to my advantage, and my coach GM Sher helped me come up with openings that I had not previously used, thus catching people by surprise.

It felt like a dream that culminated in the final round, when Hikaru Nakamura won his game and I could only draw. Of course when you enter the last round in a tie for first you want to win the whole thing, but I was ecstatic and shocked.

The Samford Fellowship (a stipend awarded to an American player under the age of 25) was not too great a surprise given my rise, but I will forever be appreciative of the opportunity it afforded me to take a gap year before college and pursue chess.

5. Coming to your academics, you were pretty focused on them. You were selected to attend the prestigious Yale University as an undergraduate. Can you tell us about your experience applying to the university and then being accepted into the program?

To this day, I remain someone with a vast array of interests and passions. I actually did my best in high school when I was busy with chess, and performed best at chess when I was busy with school. That seems counterintuitive, but somehow the two complemented each other. I imagine chess must have helped me on my application, but it is not viewed in the same light that sports are.

Outside of a few universities, there is no such thing as chess scholarships or teams. So, I had to make good grades and test scores, in addition to writing the never-ending application essays. In many ways my process was like that of others, I just happened to also be a chess grandmaster.

6. You also undertook a finance internship in a famous firm during your high school career. How did this happen? What did you learn from it?

The summer after I completed 10th grade, I interned at Fortress Investment Group. The father of one of my close friends worked at the company and thought that my chess skills -- the pattern recognition, objective assessment, strategic risk-taking, etc. -- would be applicable to the type of work at the hedge fund.

It was a fascinating experience that taught me how to analyze trends, though it also allowed me to realize at a young age that I did not want to pursue a career in finance.

7. Coming back to your time at Yale University, can you tell us about your overall experience during your studies? What did you major in, what was most interesting for you to learn, etc.?

I loved my time in college. I was exposed to so many different people from all over the world. I majored in history, and my courses helped me develop the reflex to consider WHY things are the way they are. It is essential to ask that question; context and nuance are so important. I also took some interesting psychology and film courses. I've always loved movies, but wow did I gain a deeper appreciation for the entire filmmaking process.

8. You continued playing chess despite focusing on your academics as well. How was the balancing act for you?

Following my gap year, chess really took a backseat to school and the other activities in my life. I played in tournaments while on breaks during my first year, but it wasn't the same. There were so many new things to explore in college, and chess was teetering between being a remnant of my past and a part of my future. Truthfully, I never intended to stay in chess post college.

The life of a professional chess player is really difficult, as it requires copious amounts of travel and very little financial stability outside the top, say, 25 players. In some countries, the government supports chess, but that's not the case in the U.S. There were no guarantees that, despite nearing the top 100 players of the world back in 2012, I'd ever crack that upper echelon.

If even possible at all, I would have had to be steadfastly devoted to the game. At that point in my life it just wasn't feasible, especially considering I was not motivated to study hours of chess after a long week of coursework. During the summer after my first year my rating plummeted and I pretty much stopped playing altogether.

9. After graduating, you started your own venture called The Sports Quotient. Can you tell us a bit more about this? It is also extremely interesting that you interned at Sports Illustrated as a writer. How did this happen and what was your take from this exposure?

My time at Sports Illustrated was definitely enlightening about the media industry. At SI, I served largely as a fact-checker but also was able to do some research and pen a couple of bylines. The work required meticulous attention to detail. Every single word had to be examined, sometimes quotes had to be verified. The internship taught me a lot about hard work.

As for The Sports Quotient, I started the site with one of my best friends, my brother, and another friend from high school. We thought that the way sports were talked about, with few exceptions, was not analytical enough. Nowadays, it's all the rage, but back in 2012 it was less common. We built The Sports Quotient into a promising platform for college students to write about sports.

It's a shame we never had the resources to really make a push, though over the course of six years we injected quite a bit of our own money into creating a legitimate site for sports journalism grounded in analytics.

Many of our writers have gone on to work for established companies or even professional teams. Sports Quotient's founder and initial CEO, Zack Weiner, now is the president of Overtime, a huge sports network. I'll forever be grateful to have had that opportunity to lead a team that was so incredibly dedicated to disseminating knowledge.

10. You have played for the US Olympiad team, have coached the Women's and Junior Teams, and are now broadcasting for online chess events as well. How have these experiences been for you and what do you hope to achieve with your career in the near future?

Playing for the United States was a tremendous honor that I was fortunate to have on 3 occasions (the 2009 and 2011 World Team Championship and the 2010 Olympiad). Competing against the world's greatest players is an immensely challenging and rewarding experience. While I didn't see much game action in 2009 and 2010, I would work tirelessly for those who were in the lineup, particularly GM Alexander Onischuk.

It was eye-opening and informative to collaborate with a player of that caliber. In 2009, our team won the silver, while in 2011, I managed to score a silver medal for reserve board. Having a medal placed on your neck at such a prestigious event is a feeling that can hardly be replicated.

Coaching the Women's Olympiad team has been great, too. It's so different as a coach: you're responsible for preparation, but once the round begins you are not even allowed in the tournament hall. So, I try to analyze as many opening lines as possible to give our players the best chance to put their opponents in an uncomfortable position. Although it's impossible to prepare for every last line, when something goes wrong, it's gutting.

I am not responsible for any of their successes - when they win games it is because of their skills. My duty is to shoulder as much of the pre-game work so that they can conserve all of their energy for the battle at the board. At the last two Olympiads, the U.S. Women's team has finished in a tie for fourth place, which is an especially huge accomplishment given how much the top teams out-rate ours. The team has fought on the top boards until the very last round.

As for commentating, it brings me incomparable joy. The action unfolds in real time, so everything is spontaneous for me. If there is an important tournament going on, chances are you can find me providing coverage for Chess.com, on Twitch, or on behalf of the event itself. My lone goal is to help people enjoy and understand the chess that is happening before their eyes.

When analyzed the right way, chess can be a digestible game. Of course there is some prerequisite knowledge (like how the pieces move), but if viewers are not taking away at least one nugget of knowledge from the shows that I do, I am doing something wrong. Learning is enjoyable for most people, but being lectured at is not. So, it's a delicate balance of edutainment -- it's essential to be a show that people want to watch, but my priority is helping people improve.

11. What can you say about chess as an esport?

Chess absolutely has potential. The lack of "luck" in chess definitely works against it to some extent. After all, beginners don't want to know that they will not win a single game against a grandmaster in 1000 tries or perhaps ever. That is hard to swallow and quite demotivating for some. On the other hand, that exact challenge has drawn many competitive gamers and prominent streamers to chess.

Chess is a perfect information game that is rich in complexity, but in many ways it is actually great for broadcasts as viewers can be informed why a move was played, how the opponent should respond, how that response should be met, and so on. A major issue of course is that the gameplay itself is not visually appealing in the way that games like Fortnite, League of Legends, Valorant, etc. are.

It's clear that chess has untapped marketability and potential. World Champion Magnus Carlsen is an amazing ambassador for the game, and when he plays the entire nation of Norway seems to tune in.

He has been featured in an episode of the Simpsons, starred in a Porsche commercial, and modeled for G-Star Raw. He is an avid football fan and achieved the top spot in Fantasy Premier League. There is no denying the impact that his presence has had on the chess world, and how chess has permeated other branches of media and society thanks to him.

A number of chess personalities have been around for years on Twitch and YouTube and have planted the seeds to make the current chess boom possible.

Chess is spreading to an incredible amount of new viewers and potential players. Although countless people have welcomed the influx of chess players with open arms, there has been push-back. Elitism exists in chess; people see an ELO rating next to their name that states the relative strength of the player. Some top grandmasters have called the content of lower-rated players "brainless" and "nonsense."

Events such as the ongoing Magnus Carlsen Tour and the FIDE Online Olympiad are amazing for the game, full stop. But they are tailored to the experienced player, as tournaments across all platforms historically have been.

Chess is becoming more visible, and that unquestionably is a good thing. Building the community for hungry chess learners will only benefit the established organizations. Tournament chess is played in silence, so giving the game a voice has been an important shift. I think the momentum will continue.

12. Finally, what advice could you give to youngsters who wish to take on different ventures in their lives as well as continue playing chess?

Chess is a game that can benefit you in so many ways. It helps train your pattern recognition, strategic thinking, and time management. Chess does not have to be a serious career. It ultimately is a game that should be considered fun and you can reconnect with it at any time.