30 years on, West Indian 'rebel' Stephenson has no regrets

New Delhi, March 14 (IANS):

It is 30 years since a West Indies cricket team did something unimaginable and most detested – 18 black men smuggled themselves into South Africa to entertain an apartheid regime that looked down upon them as menials.

The rebels went on two tours to pocket $130,000 and didn’t mind being treated as second class citizens and be labelled as “honorary whites”.

They lost the so-called Test and One-Day series on their first visit, but won both the second time around a year later in 1984.

They have no remorse and they still think they became the vehicles of change in the thinking of whites, hastening the dismantling of the regime by the end of the decade.

The roll call was highly impressive: Lawrence Rowe, an idol of Viv Richards, Alvin Kallicharran, an elegant left-handed batsman, Clin Croft, Sylvester Clark, two fearsome fast bowlers, Bernard Julien, dubbed poor man’s Gary Sobers, and wicketkeeper David Murray to name the more popular guys.

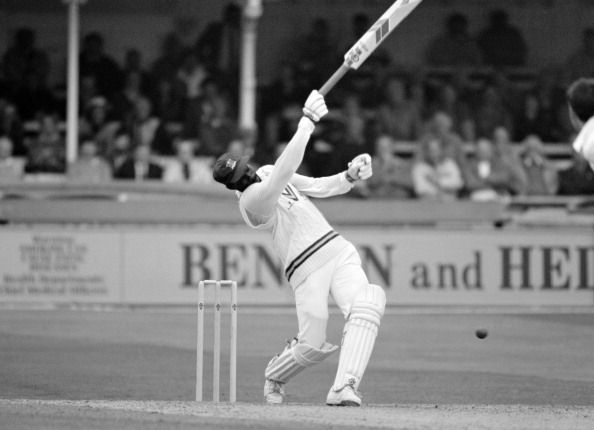

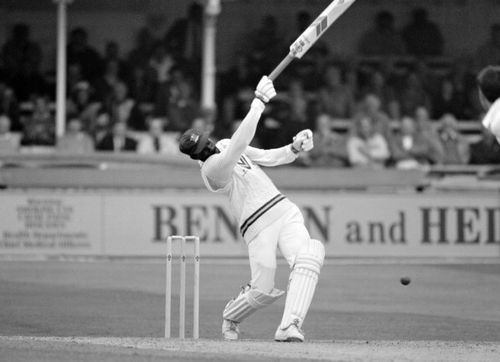

The man who lost out the most was Franklyn Stephenson. He could have ended as one of the top all-rounders of the game if only he had realised what he was losing by going with the rebels.

The Barbadian, then 23, never got to play international cricket after being banned for life by his board.

Stephenson, now 53, is clear in his mind that he has done no wrong and so has no regrets. He was a part of the 1982-83 and 1983-84 squad.

“I was 23 with a wife and two kids. Even before my life started, it was finished. I had lost seven jobs before joining the series. From some I was fired because I wanted to play cricket,” Stephenson told IANS in an interview from Bridgetown where he runs a cricket academy at a private estate and doubles up as a golf pro.

With no hope of playing for the West Indies, Stephenson went on to play county cricket for Nottinghamshire after a brief stint with Gloucestershire, and ended his career with Free State in South Africa. He remains a rare breed whose career spanned across four continents.

Stephenson was widely regarded as a great all-rounder never to have played for the West Indies. He was the first fast bowler who pioneered the art of slow delivery and used it effectively.

“There was no money in cricket. We had to sustain our family and the series offered us some good money,” said Stephenson, whose travails after the series have been documented by CNN’s World Sport Presents: Branded a Rebel.

The all-rounder, who at his peak replaced Richard Hadlee at Nottinghamshire, still remains an outsider in West Indies cricket even after 30 years. Nobody even wants his expertise as a coach.

“It is all because of the rebel series. I am still an outsider. What the board did was a blight on the cricketers,” he said.

Besides receiving a ban from the board, they were ostracised socially and professionally.

“It took a toll on the life of cricketers like David Murray. Some cricketers could never recover from the ban and their social life was in a big mess,” he said.

“I spend my time training kids and playing golf. But at times I feel sad at not getting a chance to represent the West Indies. But still I had some great time playing domestic cricket in England, Australia and South Africa,” he added.

Stephenson, however, is now a happy man seeing the West Indies win the World Twenty20 last year.

“West Indies cricket is improving gradually. It feels good. We have a bright future,” he signed off.