7 rules in cricket that need a relook

Cricket is a pretty complex game, consisting myriad rules and regulations. The fact that there are three different formats, and there are different rules for each of them, further adds to the complexity of the game.

The rules and laws of cricket keep changing with the changing demands of the game. The ICC, at times, makes some rule changes to make the game more appealing for fans and eliminate controversial rules that may discriminate teams. For example, the ‘Boundary count’ rule in the case of tied super overs was abolished after England won the 2019 ICC World Cup final on that basis. Similarly, the ‘Supersub’ rule, which primarily benefitted the team winning the toss, was scrapped within a few months of its introduction.

Nevertheless, there are a lot of current rules that appear unjust and need to be relooked by the ICC. There is a huge uproar whenever a team suffers because of such rules,, but things get swept under the carpet when the next series or tournament commences.

On that note, let's take a look at eight rules in cricket that need to be reviewed.

#1 Soft signal for catches

In the fourth T20I of the recent series between India and England, Suryakumar Yadav announced his arrival on the international stage with a superlative knock studded with attractive and innovative strokes.

The Mumbai batsman reached his half-century off just 28 deliveries. But just when he was looking good for a big score, he got out to a rather contentious call. Yadav played a ramp shot that went to Dawid Malan at fine leg.

The umpires were not sure whether the catch was taken cleanly, so they referred that to the third umpire. Nevertheless, in accordance with the then existing rules, the umpire had to give a ‘soft signal’, which in this case was given as 'out'. The third umpire could not overrule the on-field call even though one of the replays suggested that the ball touching the field. Other angles did not seem to suggest the same, so in the absence of ‘conclusive evidence’, the on-field call stood.

The soft signal generally depends on the intensity and conviction of the appeal from the fielding side. For example: in the recent Test series between India and England, Ajinkya Rahane was unsure about the slip catch of Ben Foakes being taken cleanly, so the soft signal was 'not out'. After watching the replays, the third umpire found conclusive evidence of a clean catch, so the soft signal was overturned.

On the contrary, Ben Stokes took Shubman Gill’s catch seemingly on the bounce but appealed confidently,, which elicited a soft signal of 'out'. However, the replays confirmed that the ball had touched the ground before the catch was taken, so the batsman was adjudged 'not out'.

In light of the above instances, it would be prudent to give the third umpire the authority to make the judgement without any 'soft signal', as he is the most equipped to take an informed decision based on numerous camera angles at his disposal.

The BCCI decided to do away with the soft signal rule in the IPL, something the ICC should look to do in the international game too.

#2 Umpire’s call for LBW

The umpire’s call for leg-beforewicket dismissals effectively means there can be two outcomes of the same event.

Even though the umpire’s view or judgement is given due importance, it is quite strange that a ball deemed to be hitting the stumps (just less than 50%) can be not out, while the ball just grazing the stump or bail can be out. Like the soft signal, the degree or intensity of appeal plays a big role in the umpire’s decision in this case too. Moreover, the body language of the batsman and his follow-through movement after the ball can be a deciding factor as well.

Further, the umpire’s call on impact is another debatable thing. 'Impact' is a factual aspect, not a projection. Hence, there should not be a grey area in ‘impact’. To get clarity in this regard, consider these two examples: Rohit Sharma’s dismissal in the fourth Test against England in the recent series returned 'umpire’s call' both on impact and hitting the stumps. As the umpire had adjudged him out, the decision was not overruled.

On the other hand, in Ajinkya Rahane’s case in the second innings of the first Test, the impact was the umpire’s call, as the ball was hitting the stumps, but the umpire had ruled him not-out, so he survived.

On one occasion, even though the ball was hitting the wickets, just because it was 'umpire’s call' on impact, the bowler was robbed of a wicket. In the other case, the batsman was unlucky to head back to the pavilion despite there being umpire’s call on two fronts. Thus, the impact should be either ‘in’ or ‘out’, which would help in reducing the complexities.

The ICC should come up with suitable criteria that would help in having more consistency in decision-making. Ideally, even if the ball clips the stumps, the decision should be out. The ball tracking gives a projection and is not an actual event, and there is a probability element involved. Nevertheless, it should not matter what percentage of the ball is hitting the wickets.

In tennis, where the ball is ‘in’ even if it touches the line, a similar principle should be involved in the lbw call in cricket.

#3 Inconsistent free hit and wide rule for no-balls

The current rule regarding no-balls suggests that the delivery immediately after a no-ball is a ‘free hit’, and batsman cannot be dismissed off it. However, if the bowler bowls two consecutive no-balls, there ought to be two free hits to follow, but in reality, just one free hit follows the second no-ball.

Consider two cases (overs) as follows. The deliveries are denoted by alphabets. The alphabets in bold are the deliveries on which the batsmen cannot be dismissed.

Case 1:

Bowler bowls consecutive no-balls on deliveries A and B. Thus, the deliveries on which the batsmen cannot be dismissed are A (no-ball), B (no-ball) and C (free hit).

A B C D E F G H.

Case 2:

Bowler bowls no-balls on deliveries A and C. Thus, the deliveries on which the batsmen cannot be dismissed are A (no-ball), B (free hit), C (no-ball) and D (free hit).

A B C D E F G H.

The same instance (two no-balls in an over) invites different sanctions, which should be rectified. Either the free hit rule should be abolished,, or consecutive no-balls should have the same number of free hits to follow.

Similarly, if a bowler bowls a wide and no-ball simultaneously, he is penalised for just one offence (just one run awarded). However, if he does it on separate occasions, two runs are awarded.

This rule is similar to the old no-ball rule (amended in 1998),, wherein only the runs scored on a no-ball were counted without adding the extra one run for a no-ball. This rule should also be amended to bring in more consistency.

#4 Umpires should not be allowed to extend play even if a result may be possible shortly

In the second ODI of India’s tour of South Africa in 2018 in Centurion, India bundled South Africa out for a paltry 118 in 32.2 overs.

Since there was a lot of time before the scheduled lunch, India came out to chase their target immediately. They were 117/1 in 19 overs when umpires called for lunch, as the ICC rules did not allow for further extension of play.

It was quite a farcical situation, as the teams had to come back after 40 minutes break to complete the formalities, with India romping home to a comprehensive win. Both the teams were disappointed with the, rule,, with the Indian captain Virat Kohli even discussing the matter with the on-field umpires.

Such situations in cricket are pretty rare, but the umpires should have power to deal with them on a case-to-case basis. Further, if both the teams are willing to continue, the umpires should have the right to allow them to do so.

#5 Concussion substitute for a player carrying another injury

With a view to ensure that teams are not inhibited because one of their players suffers from concussion, the ICC introduced the ‘concussion substitute’ rule in 2019.

The rule states that the team can replace a concussed player with a ‘like-for-like’ player, who has to be approved by the match referee. While the rule is a welcome move, it should be ensured that teams don’t end up taking excessive advantage of it.

There was a lot of furore in the T20I played between Australia and India in Canberra in December 2020, as Ravindra Jadeja, who had already been plagued by a hamstring injury, copped a blow to the helmet, leading to a concussion.

India requested for Yuzvendra Chahal to come in as a concussion substitute, which was approved by match referee David Boon. That did not go down well with the Australian team management, and their head coach Justin Langer had a heated argument with Boon.

To rub further salt into their wounds, Chahal turned out to be the star performer on the day and was adjudged the 'Player of the Match' for his haul of 3-25. In this case, India were well within the rules to opt for a concussion substitute, but it proved to be an undue advantage, as Jadeja was already down with an injury.

This rule needs to be tweaked, wherein the match referee should disallow a request for replacement of a player who has another injury in addition to a concussion.

#6 Ball becomes dead immediately after the umpire gives the batsman out

As per the rules, whenever an umpire rules a batsman out, the ball immediately becomes dead. Even if the batsman successfully reviews the umpire’s decision, he does not derive any benefits (runs) from that delivery.

One such instance happened in the second ODI of the recent series between India and England in Pune. Rishabh Pant was given out leg before wicket, a decision which he immediately challenged. Replays suggested that the batsman had hit the ball with the bat. But even though the ball trickled down to the boundary, Pant and India missed out on four valuable runs,, which might have been key in the context of the game.

This rule should be reviewed so that it does not punish the batting team for an umpiring error. There could be an argument that the fielding team doesn’t bother about the ball once a decision is made by the umpire. Hence, a change in the rule making the ball itself dead and re-bowling it could be a better way to deal with such a scenario.

#7 DLS target and DLS par score

In rain-affected matches, the Duckworth Lewis Stern (DLS) method is used to set a target corresponding to the number of overs available.

The rule is also used to calculate the par score for a team at any given time,, which varies depending on the number of wickets they have lost. This rule takes into account the resources, namely overs and wickets in hand,, while making the calculations. However, the rule seems complex, as there is a big difference in the par score and the target for the same number of overs. To make it clearer, consider the following case:

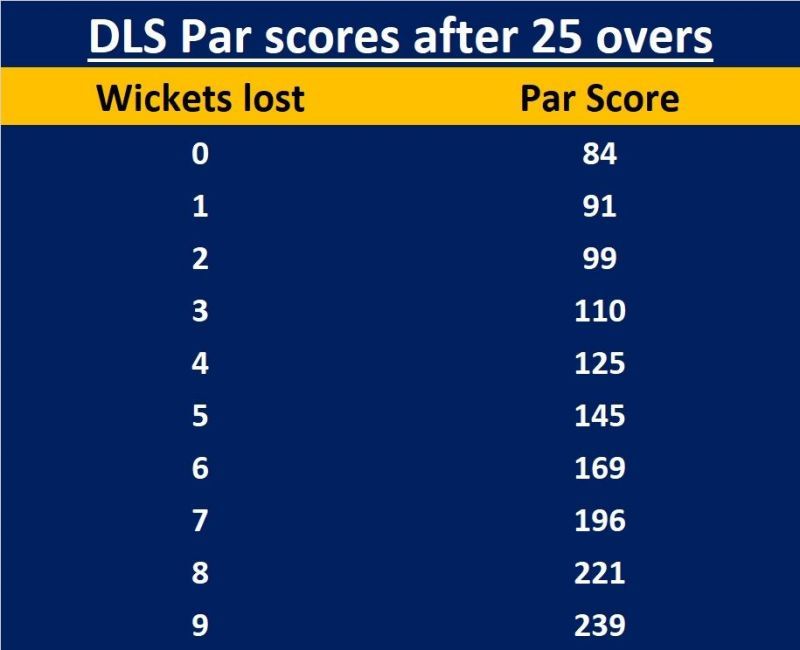

Team A bats first in a 50-over ODI and puts 250 runs on the board in 50 overs. Team B starts conservatively and reaches 98/3 in 25 overs when rain halts play. The par scores corresponding to the loss of ‘n’ number of wickets after 25 overs are as shown in the table below.

If there is no further play in the game, Team B would lose the match by 12 runs, as the par score for the loss of three wickets after 25 overs is 110. Had they lost just one wicket, though, they would have been ahead by seven runs.

Now, consider that the match is reduced to 30 overs. As per the DLS method, the target for Team B is 152 runs in 30 overs. Thus, after the resumption, they would require 54 runs off 30 deliveries.

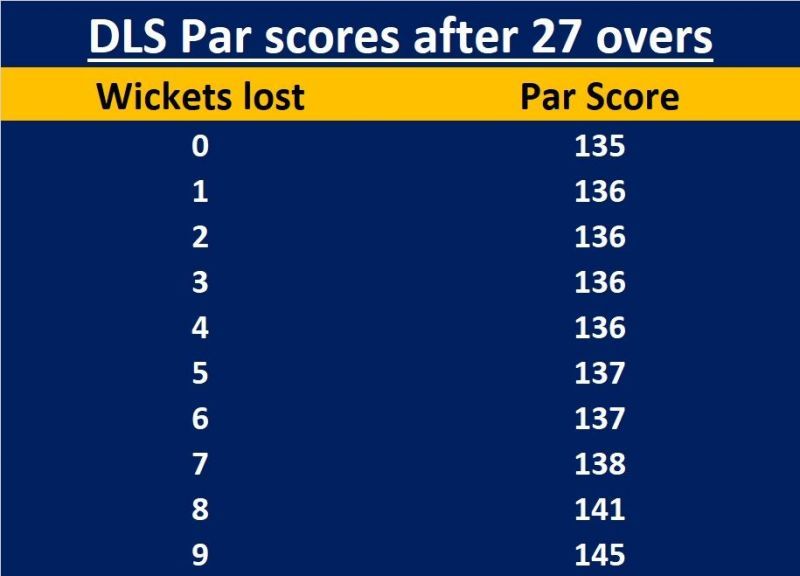

Considering the high required rate, let's assume that the batsmen play aggressively and score 35 runs in the next two overs. Team B are now at 133/3 and require just 19 runs in the remaining three overs.

If there is a rain interruption at this stage and no further play takes place, the DLS par score would come into the picture. The DLS par scores corresponding to the loss of ‘n’ wickets after 27 overs are as shown in the table below.

In that case, despite scoring 35 of the required 54 runs in two overs, Team B would fall short of the par score by only three runs. However, had the match been reduced to a 27-over affair instead of 30 after the first interruption, the target for team B would have been just 128.

Thus, the timing of the interruption plays a crucial role in the outcome. The rule needs to be modified, wherein one entity should be devised to decide the winner instead of two - DLS par score and DLS target.