The all-time 'would have beens' Test XI

Earlier this week, Wisden came out with its All-Time Test XI to commemorate its 150th anniversary. Since then, almost everyone from Michael Vaughan to my neighbour’s dog have come out with their version of the same in addition to the expected dose of criticisms and witticisms that are due when something of this nature is attempted.

It is indeed difficult to select a conclusive all-time eleven. It is almost equivalent to comparing cinematic blockbusters over the years. For example, would Sholay have been a bigger hit than 3 Idiots if it had released now? Secondly, my opinion of this issue may be vastly different than yours. I might consider an expert player of spin bowling more valuable than someone who can handle the short ball well.

I have thus decided to tread on safer territory and come up with my alternate version of an all-time Test XI. My list consists of players whose careers were not long enough to elevate them to the status of a great or who showed brief sparks of brilliance in a career ridden by mediocrity. My logic is that there was a method to this madness.

As I had pointed out in an earlier article, Sourav Ganguly averaged 66 at number 4, and had Sachin Tendulkar not been so persistent about his favourite position, we might have been reading a different chapter of cricket history today. Similarly, most of the players in my list would have had at least a couple of phenomenal performances and some are greats in their own right. Why I have classified them as a “would have been” is because I feel that their potential was not realized to the fullest in the role I see them in – be it better options available, selectors’ indiscretion, politics, injury, the “born in an era earlier” syndrome or perhaps even the player’s own naiveté. So here goes nothing.

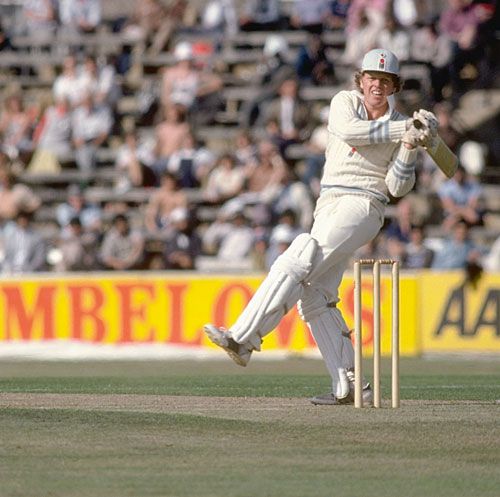

I would have the duo of Barry Richards and Sid Barnes opening the batting for me. Richards divides the cricket world into two hemispheres – one which speculates what would have had been had he turned out for another country or had South Africa not been forced into sporting isolation and the other which reasons that, after such a bright start, he would have only gone downwards. Either way Richards remains one of the biggest enigmas of international cricket.

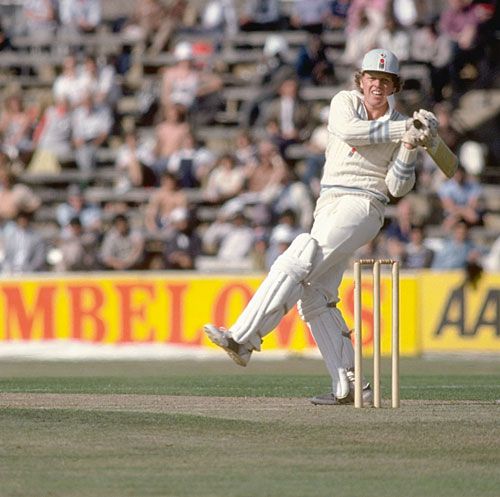

When you talk about Barnes in cricketing folklore, the other Syd (who made it to Wisden’s list) is the first name that comes to your mind. This does not make Sid any meaner as a cricketer. He played as an opener in 10 of his 13 Tests and all of his 3 centuries and four of his five half centuries came from this position. This includes the magnificent 234 which he made in collusion with the Don (who also coincidentally scored 234) in a world record partnership of 405 against Wally Hammond’s Englishmen.

Duleepsinhji played half of his 12 Tests at number 3 but made full use of the opportunity scoring two centuries along with three half centuries. On his day (which was quite frequent), he was the best player of slow bowling on wet rain-affected pitches which were more of a norm than an exception during his playing days.

At number 4 – the position I have talked about in so much detail over the last few days – comes my most left field selection. Boof may be more popular for his resemblance to Bruce Willis or his thoughts on Stuart Broad but Darren Lehmann was quite competent as a batsman in his heyday. The fact that he averaged almost 45 but was far from a regular in the Australian Test side tells as much about the bench strength of that particular team as of his bad luck at being born at a wrong time. For a period in 2003, he averaged over 90 with the bat at number 4 against West Indies and Bangladesh with a series of scores that reads like this: 160, 66, 96, 7,110, and 177. A year later, he was dropped from the team in favour of Michael Hussey.

Bringing back normalcy at number 5 is the calm and composure of Neil Harvey. Harvey started out as a number 6 but continued ascending the ladder literally as he spent the greater part of his career at number 4 before finishing at number 3. The reason for this out-of-turn promotion though was his exemplary performances at number 5. In only his second innings, Harvey produced a sterling 153 against India which made him the youngest Australian centurion at that time. He followed that up with a 112 from the same position in the celebrated Leeds Test of 1948. This was followed by 178 on the last day of the next year against South Africa in Cape Town followed by another famous knock of 151 at Durban. All this happened over a span of 12 Tests over two years. Almost ten years later when he again got a chance to bat at this position he made the most of it by cracking 54 against Pakistan in Karachi.

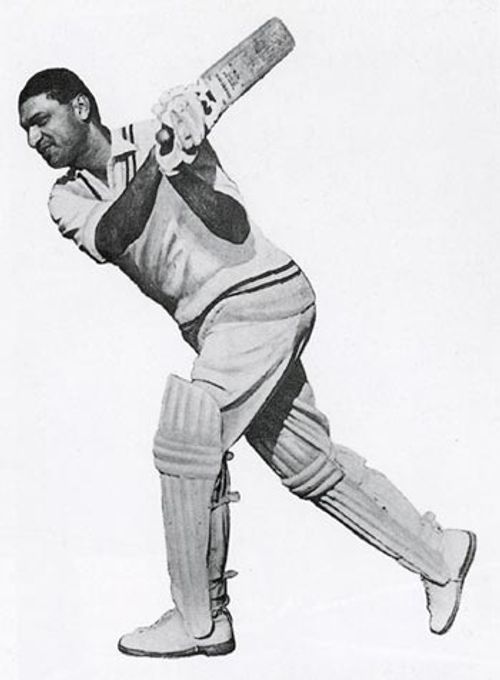

Number 6 is reserved for the batting all-rounder which leaves me in a bit of quandary. Ideally I would prefer a batsman who could be more than a handy bowler but, in extreme batting friendly (or bowling friendly) conditions, I would require the services of a full-time fifth bowler. For the former position, I would push for Polly Umrigar. Umrigar flitted around the batting order but still ended up with the most important numbers – most Tests, most runs, and most hundreds. As an off-spinner he was accurate; as a medium-pacer he could open the bowling and send down more than a part-timer’s share of outswingers. Add to that his versatility as a fielder and his shrewd captaincy and you would pity that he wasn’t born in a different era for India.

If however I needed someone who could bowl a little more than a little more, I would turn to Michael Bevan. I can hear the sneers already but, for his dismal Test record, one has to admit that Bevan was not utilised as properly as he should have been by the Australian selectors simply because they were spoiled by the problem of plenty. Being a chinaman, he was a difficult bowler to face up to which was exemplified in the series against West Indies in the ’97-’98 series where he upset their applecart by taking 15 wickets in addition to scoring a couple of crucial 80s before running out of partners. He was never someone who you could bet your life on against the short ball but this would not be too much of an issue as I would require his services only on turning pitches as a third spinner and hence by default as a batsman who can bat at six or lower.