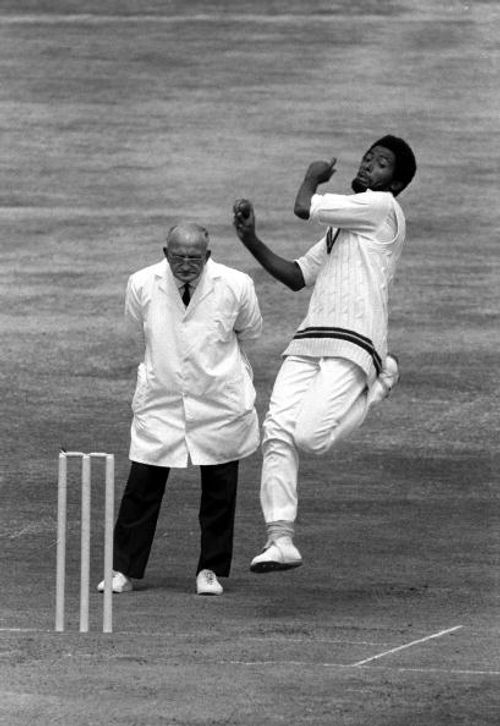

Andy Roberts: Purveyor of pain

In the days when former international umpire Mervyn Kitchen played for Somerset County, he and teammate Graham Burgess were in the habit of doing pretend commentary while they waited to bat. On one occasion, reports Vivian Richards, then a young batsman making his way, they were in particularly fine form as they described deliveries threatening and often crashing into the upper body of his teammates.

Those were the days when a youthful, quick and mean Andy Roberts roamed the shires under the banner of the Hampshire County Cricket Club, doling out discomfort and pain to helmetless batsmen. On this day he was sending them down like rockets. “Did you see that!” bellowed Kitchen, “it’s the quickest ball I have ever seen in my life. I am not going to get these smashed,” as he removed his false teeth and placed them in his pocket, “I paid too much for them.”

Brian Close, widely regarded as the toughest of characters, was struck a fearful blow under the armpits in that game. Falling “like a stone” according to Viv, he stopped breathing for a while and had to be resuscitated. Ian Botham, teenaged and not yet England’s greatest all-rounder, found himself bereft of a few teeth when one screaming bouncer from the brooding West Indian sent his glove, upheld in an attempt at self-preservation, cannoning onto his face. Unsteady but undaunted, Botham showed his mettle by spitting out the mixture of blood and enamel on the field before composing himself enough to guide his team to an unlikely victory. Next day, much of his time was spent reclined in a dentist’s chair, effecting extensive repairs to a ransacked mouth.

The wounded batsman had the temerity to hook the bustling pacer for six, unaware that the cunning Antiguan was lulling him into complacency before unleashing his quicker, more lethal bouncer. Botham admitted that he fell for the ploy “hook line and sinker,” and was lucky not to have paid a higher price.

Stephen Camacho was not so fortunate.

Roberts first set foot in England in 1972 to attend, along with Viv Richards, The Alf Gover coaching school in South London. Hampshire went to see him, liked what they saw, and signed him for the 1973 season. The West Indies came on tour in the summer of 1974 and during the tour match against Hampshire, Camacho, the bespectacled Guyanese who was expected to open the batting in the Tests, was felled by a Roberts bouncer which he tried to hook. According to the Reuters report, Camacho “was struck just below the eye and left the field with blood pouring from an ugly gash.” The batsman suffered a concussion and had to undergo an operation to repair a fractured cheekbone.

The incident meant that Camacho took no further part in the tour, and though he continued playing for Guyana for a few years he never regained the confidence he had prior to the blow. It also meant that Roberts had forced himself into the awareness of the West Indies selectors at a time when there was a dearth of high quality fast bowlers in the Caribbean. A year later, he was on the Test team.

The Antiguan seemed able to hit batsmen at will. The scorecard of a 2nd XI game against Gloucestershire at Bristol in the early part of the 1973 season shows that two batsmen retired hurt – both hit by Roberts. At Basingstoke in 1974, England batting great Colin Cowdrey suffered what Viv Richards called a “sickening” blow when he became another victim of Roberts’ faster bouncer. With the batsman falling motionless on the ground, concerned fielders gathered around him. Roberts, it is reported, hardly batted an eye, standing away from the scene, awaiting the removal of one batsman and the arrival of another.

The Antiguan seemed able to hit batsmen at will. The scorecard of a 2nd XI game against Gloucestershire at Bristol in the early part of the 1973 season shows that two batsmen retired hurt – both hit by Roberts. At Basingstoke in 1974, England batting great Colin Cowdrey suffered what Viv Richards called a “sickening” blow when he became another victim of Roberts’ faster bouncer. With the batsman falling motionless on the ground, concerned fielders gathered around him. Roberts, it is reported, hardly batted an eye, standing away from the scene, awaiting the removal of one batsman and the arrival of another.

In his autobiography, Viv goes through a list of batsmen who were hurt from deliveries propelled by his countryman’s right arm:

The first time I saw it was when he hit David Hookes in a World Series cricket match and broke his jaw. The Australian Golden Boy was wired up for weeks and couldn’t eat anything solid for a while. I also saw him hit Peter Toohey in Trinidad and broke his nose, and then later he smashed his thumb in the same game; he broke Sadiq Mohammad’s jaw in a Test match in Georgetown and Majid Khan’s cheekbone in county cricket. (Sir Viv, pp. 82-83)

The list is long.

Yet it would be a grave error to think that the unsmiling Antiguan assassin was all about brutality. Fast bowling was his trade, and like it or not, intimidation was a useful tool of his profession. Dennis Lillee, remember, said that whenever he hit a batsman with a bouncer, he wanted it to hurt so bad as to make the batsman reluctant to face him again. The intent is not to maim, it is to urge the batsman towards surrender; to make him give up his wicket without putting up too much of a fight. Roberts valued the efficacy of the short, climbing delivery, but he was as likely to defeat a batsman with skill and smarts as he was with sweltering pace and hostility.

Michael Holding often speaks of the fast bowling lessons taught to him and those who came afterwards by Roberts. It was Roberts’ advice that led to the Jamaican’s first Test wicket in his second game, and he relied on his fast bowling colleague for advice throughout their time together. Those who played with and against Roberts regarded him as a master at plotting, and highly adept at executing the demise of opposing batsmen.

Roberts was the first in a long line of great fast bowlers that came out of the Caribbean in the seventies and eighties like cars off an assembly line. His Test career ended – prematurely in his view – in India in 1983, and if his pace was less extreme at the end, he remained the same uncompromising, unemotional pacer as when he started. “If you hit me for four,” he explained, “what am I going to smile about?”