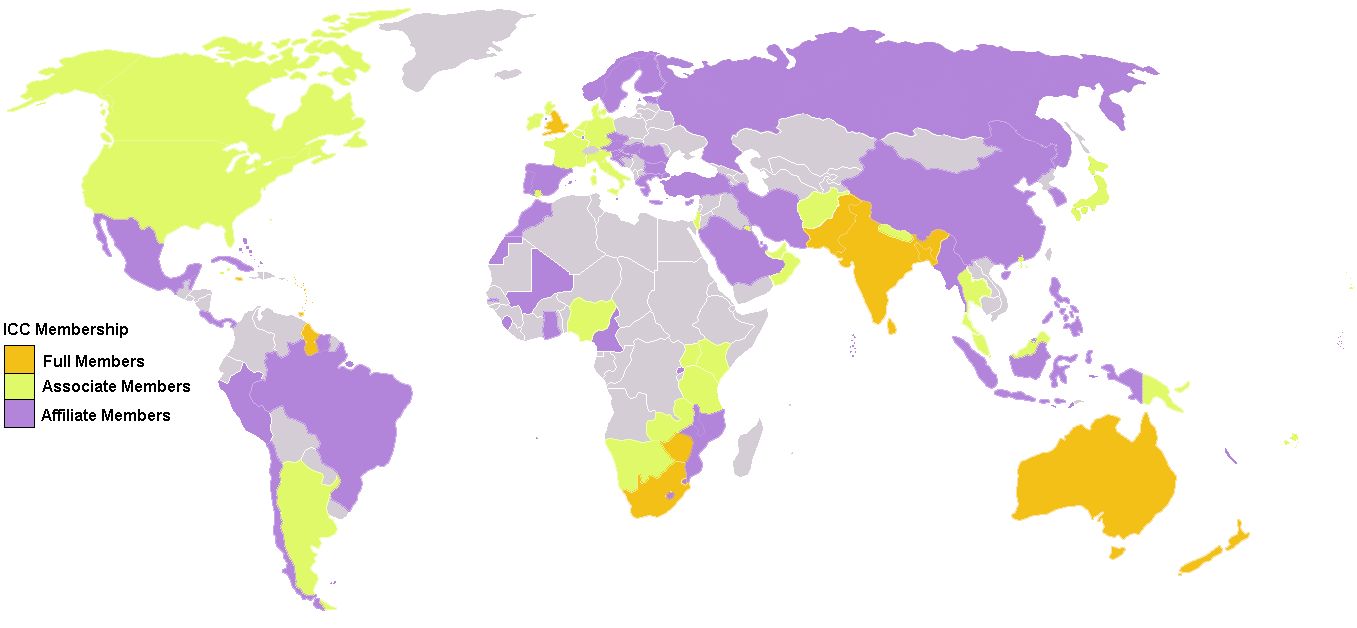

Associate Nations - The Path to Globalization of Cricket

Two weeks and a little into the World Cup, the debate on the World Cup format and inclusion of Associate nations has produced more humdingers than the actual matches. While it could be argued that these smaller teams are the reason for significantly less competition, there are points to indicate otherwise.

The first half of the group stages suggests that the matches between top-tier nations have been largely one-sided, barring the Aus-NZ edge-of-seat clash, and the matches between the associate nations have been extremely competitive.

So, is the format actually at fault? Are associate nations indeed an unwelcome commodity in the big leagues? But again, shouldn’t a “World Cup” be more inclusive? Can the ICC afford to risk another 2007 by giving the “minnows” a fair chance?

The 2007 World Cup disaster

The format of the World Cup has seen significant changes since its first edition. Starting off with 8 teams in 1975, the number of participating nations reached its highest point of 16 in 2007. Bangladesh defeated India, Ireland defeated Pakistan, and a potential India-Pakistan clash was hijacked by a Bangladesh-Ireland match.

An ominous decrease in TV ratings and attendance later, the formats of the 2011 and 2015 World Cups were re-designed to ensure that the bigger teams have every possible chance of qualifying for the knockouts, leaving room for an upset or two.

The ICC has proposed for the 2019 edition to be trimmed further to a 10-team tournament, but voices from different quarters and the performances in this World Cup will certainly make them rethink their proposal.

As Ireland’s Ed Joyce gravely puts it, “Cricket is the only sport with a World Cup that is contracting rather than expanding”.

ICC, unlike FIFA, unable to afford big teams’ slip-ups

Naysayers have also cited the example of the FIFA World Cup which has 32 teams and gives equal chances for every single team to qualify. However, cricket is a completely different sport from football – physically, tactically, as well as in terms of its stance as a global sport.

A moment of individual brilliance or sluggishness can get you a goal and win you a match in football. But in cricket, it might get you a wicket or a boundary, which may or may not change the course of the match. In the quest of winning a cricket match, a stroke of genius is only a single drop of water in an ocean.

Football has a supremely organized club structure, which at times is considered as an even higher echelon than international football. Careers of numerous players have been defined by their club performances – players like Ryan Giggs, George Weah, and George Best are bona-fide legends in spite of not having appeared in a single World Cup.

The same is not true for cricket, which relies primarily on International Cricket for its survival, with the World Cup being the highest rung of the ladder. Reputations are made in the international game, not in the IPLs, Sheffield Shields or English county cricket. Not yet, at least.

As for commercial viability, FIFA can survive without a Sweden or an Uruguay appearing in the World Cup, whereas the ICC may not be able to afford a Sri Lanka or a New Zealand failing to appear in the World Cup.

Harmful for long-term popularity of cricket

The issue at hand runs deeper than the tournament format. The issue is with cricket’s, or should I say ICC’s, attempt to be recognized as the world’s second most popular team sport, whilst maintaining financial and commercial opulence. In pursuit of striking a balance, Cricket seems to be prioritizing commercial dispositions over the game’s development.

This “safety first” approach may have immediate merit, but over the long term, the sport will contract further – hara-kiri for the sport’s global aspirations. In a long-term purview, any sport would benefit with an increase in teams, improved competitiveness, new fans, and newer markets. From a commercial standpoint, a growing number of international teams, and hence an increased audience, will certainly be a win-win for the sport and the stakeholders alike.

Increasing competitive levels cannot be achieved by changing the tournament format, the changes need to be made at a more grassroot level.

The structure of most Associate team tournaments is designed with the solitary purpose of qualifying for the World Cups. Playing in World Cups might give the Associates a one-off exposure to the big leagues, with an ‘upset’ or two leading to journalistic platitudes. But over the long run, it will not help them improve their standards.

Ways for cricket to flourish

The Associate teams may find it tough to progress with this 1-in-4 years’ acquaintance. They need constant matches against high quality teams to help them improve. If not the main international sides, the likes of Ireland, Afghanistan, Scotland should regularly play against the A sides of the big nations.

Another slightly long-term possible solution could be for the rich cricket boards like BCCI, CA, ECB, CSA to ‘adopt’ an associate nation each for certain periods. Such a role would consist of supporting the Associates in developing domestic cricket in the country; also aid them with coaching and infrastructural support, to help them mature into serious cricketing nations.

The challenge the cricketing authorities face is to nurture the sport, improve competitiveness, cultivate new audiences, enter new markets, and create a commercially viable environment, in which the Associates and Test teams can thrive with equal poise and opportunities.

A sport which has long survived with 8-10 teams and has been extremely stingy about awarding Test status; it might be time for it to open up to fresh avenues, seed previously unimagined terrains and explore unconquered territories. Cricket will not only survive, it will flourish.