Book Review - Centurion: The Father, the Son and The Spirit of Cricket by Pramesh Ratnakar

Pramesh Ratnakar’s fictional story tries to bridge the divide between mind and body just as Sachin did as a batsman.

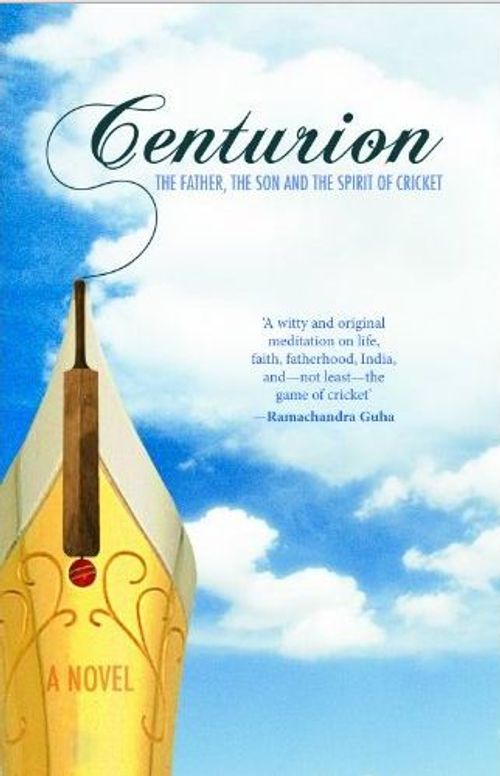

Centurion: The Father, the Son and The Spirit of Cricket

by Pramesh Ratnakar, Harper Collins India, Rs 225, 150 pages

During the 1990s and the first decade of the 21st century, cricket started creeping into Indo-Anglian fiction. It is not mentioned in the novels of established writers like Salman Rushdie, Amitav Ghosh, Vikram Seth, Anita Desai or Upamanyu Chatterjee but becomes the subject matter in various other novels. The first of its kind is the Autobiography of an Unknown Cricketer (Ravi Dayal, 1996) written by Sujit Mukherjee, a professor of English and later a publisher. Sujit played intermittently for Bihar in the Ranji Trophy during the 1950s. In his luminous account, told in graceful and understated prose, Patna becomes the unlikely centre of the cricketing universe. The joys and travails of the school, college and club cricket scene – travelling long distances in third-class train compartments, sharing out precious Gunn & Moore cricket bats are aptly depicted. This cricket novel is a nostalgic reminder of an age gone by.

The Zoya Factor is a cricket novel written by Anuja Chauhan(Harper Collins, 2008). It is about a Rajput girl named Zoya Singh Solanki who meets the Indian Cricket Team through her job as an executive in an advertising agency and ends up becoming a lucky charm for the team for the 2010 Cricket World Cup. Anuja Chauhan, the creator of Pepsi punch lines, tried her humour in a chick lit type of book based on cricket and the Men in Blue.

The plot reads like a whacky commercial — Zoya Singh Solanki is considered a lucky mascot of the Indian cricket team. The boys in blue discover that every time they eat breakfast with her, they win the day’s match. And not eating with her results in defeat. They also discover that Zoya was born at the exact moment that India won the World Cup in 1983. Zoya finds herself accompanying the team to Australia for the tenth ICC World Cup on an all-expenses-paid holiday. Cricket insiders enjoyed the gentle lampooning of the whole cricket circus, the pushy agents, the starry players and the manipulative board.

An unusual cricket-fiction book is The Taliban Cricket Club, (Aleph, May 2012) written by Timeri (“Tim”) Murari. It is based on a newspaper cutting of 2000, in which the Taliban had applied to the International Cricket Council (ICC) for associate membership and had decided to promote cricket in Afghanistan. The game has become popular there as many refugees had lived in Pakistan and not only learnt cricket but became quite proficient in it.

In the novel, a 21-year-old journalist Rukhsana returns to Kabul soon after the Taliban came to power. She learnt cricket whilst studying in New Delhi where her father is posted as deputy ambassador. When the Taliban announces a cricket tournament where the winning team would be sent to Pakistan to train, she sees it as an opportunity for her brothers and cousins to escape. So she forms a team and ironically names it the Taliban Cricket club.

However the most thought-provoking and philosophic novel on Indian cricket is by noted academician Pramesh Ratnakar. The narrative technique is unique and multi-layered. The author uses devices like an interview of a potential candidate (Professor Pramednra Vidyakar) for the post of college principal, dialogue, lyric poetry and prose narrative to explain his complex themes. Everyday conversation (hence the “hi” that opens it) turns into an interior monologue (of a character who could be Sachin Tendulkar), followed by a legal trial and a stretch of dialogue that hovers between Biblical and Vedic. There is also a fictional imagining of the psychological footprint left by Sachin Tendulkar’s father, a professor of Marathi literature, a genteel scholar who belonged to a world of books and words, on his son, a man of action.

According to the author Pramesh Ratnakar, the central idea of the book is to try and bridge the divide between mind and body just as Sachin did as a batsman. On his first tour, the precocious 17-year-old Sachin lofted the awesome Pakistani pace trio, Waqar Younis, Wasim Akram and Imran Khan because he combined mental toughness with unique batting skills and judgement of the line and length of the ball. Ratnakar thinks Sachin in such moments is like a creator, a poet. Sachin’s magic is with the bat, as the poet juggles with words. This argument is developed in the novel by the comments of the team psychologist Gordon who says that a poem is a mental construct and cricket is a physical activity. They are discussing the lyric poem written by Sachin’s father Professor Ramesh Tendulkar, a scholar and poet about his son’s batting prowess.

According to the author Pramesh Ratnakar, the central idea of the book is to try and bridge the divide between mind and body just as Sachin did as a batsman. On his first tour, the precocious 17-year-old Sachin lofted the awesome Pakistani pace trio, Waqar Younis, Wasim Akram and Imran Khan because he combined mental toughness with unique batting skills and judgement of the line and length of the ball. Ratnakar thinks Sachin in such moments is like a creator, a poet. Sachin’s magic is with the bat, as the poet juggles with words. This argument is developed in the novel by the comments of the team psychologist Gordon who says that a poem is a mental construct and cricket is a physical activity. They are discussing the lyric poem written by Sachin’s father Professor Ramesh Tendulkar, a scholar and poet about his son’s batting prowess.

The discussion also involves the erudite Anil Kumble, the engineer who became a spinner and the Wall of Certitude Rahul Dravid. Gordon finally agrees that Professor Tendulkar’s poem brings about unity between cricket and creative genius, as they overcome all obstacles.

The book thus examines the dynamics of the father-son relationship, the scholar and the cricketing genius who is also a centurion. Sachin acknowledges that his father created and worked with cultural and educational surplus and created an environment at home that allowed his son to flourish in his chosen career of cricket. The search for self sufficiency is what Sachin’s father gifted to him. The excellent chapter Classroom shows Sachin also concerned as a father about the future of his children Sara and Arjun and the world of conflict and horrors that that they will inherit. This section of this unusual novel focuses on the debates and dreams that shape father-son relationship, and how to reconcile life’s dilemmas in a creative manner for the child to aim for excellence.

Above all, it is a book about idealism and utopia. The book seems to raise the query that is it not possible to create a utopia within your own lifetime, the kind of world you would like to live in. Sachin has created a cricketing utopia for India. How did he do this? Has Sachin bridged the gap between internal and external, mind and body in some unique manner? The author discovers linkages between academics, cricket and philosophy.

These remarkable comparisons emerge in the chapters, The Interview and The Trial. As the title of the chapter suggests, it is an interview of a candidate for the post of principal at the same college where Sachin’s father Professor Ramesh Tendulkar taught. Sachin Tendulkar is eavesdropping on this college principal interview and is invisible. It sounds incongruous but then many of Sachin’s feats with the bat were also quite incredulous. The candidate, Professor Pramendra Vidyakar, is a passionate and visionary thinker who has devised a career map for all of humanity. In the interview, he encounters both hostility and encouragement from the pillars of the institution.

However just as Sachin overcame many obstacles on his relentless drive for excellence as a batsman, Professor Vidyakar counters all arguments with his persuasive ideas, logical and well timed replies and theories. This section of the book is very philosophic and the academic author brings in a plethora of ideas about the God of cognition and Non cognition, physics and philosophy. The interview take many dimensions, conflict and humanity, and includes the thoughts of 14th century Maharashtrian poet-saints Muktabai and Janabai, Japanese poet-saint Basho, English lawyer-philosopher Sir Thomas More, 19th century American Indian leader Chief Seattle, and the poetry of Professor Ramesh Tendulkar.

These philosophic arguments reveal that cricket becomes a lyric on the playground due to the string of uncertainty that surrounds the game. The Centurion is an inventive and unusual book which looks at Sachin Tendulkar’s career from a philosophic perspective and his impact on generations of cricket lovers.

The tenuous links between sport and study, education and utopianism and man’s inner and outer worlds are also well examined in this book. Overall a complex work of cricket fiction, which requires careful reading as it talks about the whole problems of existence, using Sachin’s batting excellence as a metaphor for life.