Bradman vs Ponting: The question of greatness revisited

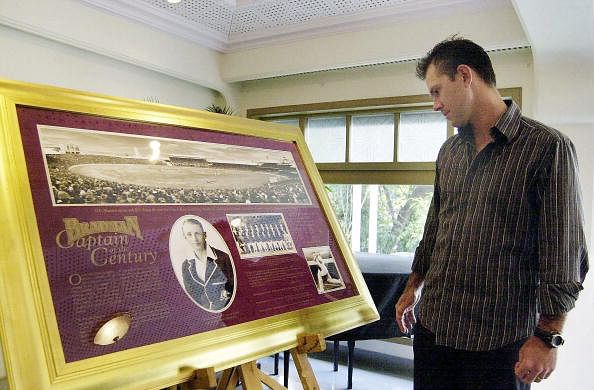

FILE PHOTO: Who overcame the greatest odds? Bradman or Ponting?

Is something missing in the way we record and reward greatness in sport?

Over the last four weeks, Australian fans voted on the Greatest Australian Test Player of All Time.

Cricket Australia, who work passionately for the growth of the game, have put up the results here.

Each election day, fans compared two greats. Candidates who got through one round figured in the next and so on until the knock-out phase. Bradman met Ponting in the final – and won, with 52% of the votes going in his favour. The casualties included Steve Waugh, McGrath, Border, Lillee, Gilchrist, Warne and the Chappells.

Comparing bowlers, fielders and batsmen, is unfair. And so is comparing across epochs. Even so and even if votes unfairly end up favouring only batsmen, the mechanics are as fascinating as the mandate.

The contest started out with all the obvious names. Then just when fans were about to honour consistency, longevity, resilience and versatility, they pinned themselves to a single figure – 99.94.

Ponting played three times as many matches, scored nearly twice as many runs, nearly five times as many fifties and had 41 tons to Bradman’s 29. Ponting played in grounds around the world against twice as many teams. He faced some of the most effective bowlers, fielders, wicket-keepers and captains in cricket history. And this isn’t counting his ODI feats during that same period.

Yet, fans seem trapped in a trance, voting again and again – for Bradman, recency be damned. Frankly, everything else be damned.

But if we don’t define ‘great’ and ‘greater’, how on earth do we get to ‘greatest’?

Federer, Anand, Pele, Phelps – they were great because they were a) tested severely, b) consistently, c) for the longest possible period and d) in the widest range of conditions. Remove one parameter and their greatness recedes by a length. Remove another and it recedes by several lengths. But we are capricious, when we should be considered.

The thumb up (or down) is fine when you sit clapping and cursing in a single match or tournament. No one’s judging greatness anyway. Not within 90 minutes or a day or five days. But across a hundred years, picking from hundreds of players, should we be more judicious?

The force of an explosive is simply defined – the ability to shift surrounding mass. This makes one more destructive than another – depending on its relative ability to ‘shift’, or destroy. The most dangerous – or the most effective, depending which side you’re on – are those with the greatest ability to destroy.

A player must defeat great odds, to be called ‘great’. No wonder Bradman was, rightly, ‘great’. But the ‘greatest’ must defeat the greatest odds.

This isn’t peculiar to Australian cricket or Indian cricket but to all cricket and all sport.

In spite of the mountain of evidence, if fans still believe that Bradman faced greater odds, so be it. But it helps now and then to pause and ask: Really?

With Bradman securing only 52% of the vote, it appears that a growing number are doing just that.