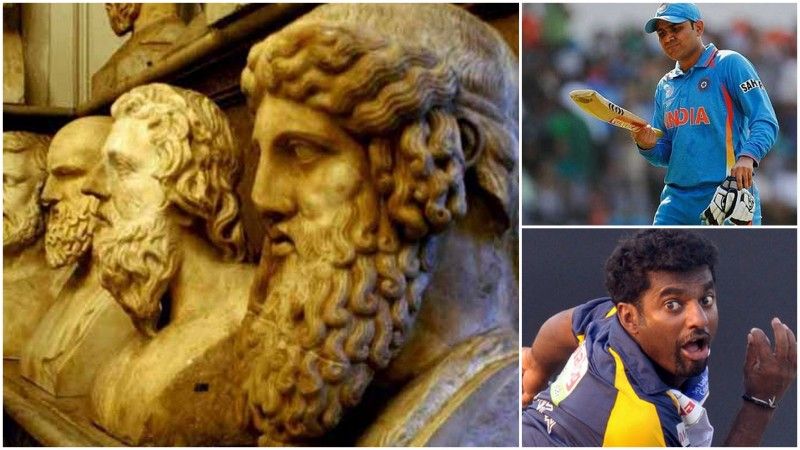

Cricketers and their philosopher alter egos

Virender Sehwag

Like Voltaire, Sehwag is an advocate of the basic freedoms of life – he believed in the freedom of expression and voiced this through his gusto strokeplay. A devotee of radical freedom, his career has been a refutation of the philosophy of Rene Descartes: "I [don't] think, therefore I am."

He taught us that an individual’s freedom to act transcends any rule and that pitches, bowlers and match situations are nothing but illusory constructs. If it moves, hit it. If it doesn't move, hit it. If you can't quite see what it is, hit it anyway.

Shoaib Akhtar

A devotee of Freud’s theory of the Super Ego, he has added much to the school of Existentialism, with his poignant writings on refusing to believe in anything that is not tangible, including God. Like Epicurus, he has earned a reputation as a teacher of self-indulgence and excess delight.

He was soundly criticized by a lot of polemicists (Sachin fanboys), because he was thought to be an atheist.

Rohit Sharma & Ravindra Jadeja

Every bit our versions of the modern day Auguste Comte, both are strong proponents of altruism, a doctrine that says people have an obligation to help or serve others – opposition bowlers, batsman and fielders alike

David Warner

A Nietzschean in the true sense of the word, he does not believe in giving the opposition even a quarter. Widely regarded as an anarchist, he believes one should not be bound by the shackles of timidity.

The sledging Australian does not allow the ICC, umpires, match referees or even the “spirit of cricket” drivel to bound him. And the weak, babyfaced, average Joes are often deserving of a punch to the face.

Daryl Cullinan

Like William James, he judges that the impact on the behaviour of the environment (Australian close-in cordon) must be considered during (innings) structuralism. In his theory of emotion, James contends that when we see a snake, we run; therefore, we fear snakes.

Cullinan attempted to use this school of thought to explain why, if one sees a curling delivery from Shane Warne, one must fear Warne and run.

Salman Butt

A follower of Albert Camus’ school of thought, he is of the view that the game is fundamentally absurd, and that there is no inherent difference between winning and losing.

Immanuel Kant could’ve very well championed Butt’s case in court - while there remains no doubt that Md. Aamer’s foot was over the line in the phenomenal world (the world of appearances), there is no way to know if it was in the noumenal world (the world as it really is).

We can, of course, never know anything about things as they really are.

Shane Watson

Not unlike Martin Heidegger, Watson is not the biggest fan of (DRS) technology, as manifested in his oft unsuccessful “reviews”. According to him, over-reliance on technology removes and abstracts us from living any kind of authentic life (at the crease). What remains is what your eyes reveal to you. The BCCI would agree.

Shane Warne

Practitioner of Socrates’ philosophic arts, the spin wizard is a master of inductive reasoning: ("You got an MBE for scoring seven at the Oval?"). Also the face of Marxism, he revels in pitching deliveries on the right before getting them to veer sharply to the left.

Shivnarine Chanderpaul

Ever the perfectionist, “The Crab” has built a stellar career around working out the intricate angles – borrowing heavily from Descartes’ analytical geometry and Cartesian coordinate system.

He also advocated dualism, which is basically defined as the power of the mind over the body: strength is derived by ignoring the weaknesses of the human physique and relying on the infinite power of the human mind.

Murali Vijay

The Indian opener seeks to emulate Siddhartha Gautama’s search for enlightenment by occupying the crease and not budging until he the truth is obtained. Squatting at the wicket and leaving balls outside off stump, while the world wishes he'd get up and get on with it.

Muttiah Muralitharan

The “Schrodinger’s cat” thought experiment can be called upon to demonstrate the apparent conflict faced by batsmen while fronting up to the Sri Lankan genius. The decision problem - whether to come down the pitch if it is a routine off break or whether to play from the crease if it is a doosra - is formally undecidable.

In other words, until the time leaves Murali’s hand and hangs in the air, the nature of delivery is completely unknown and therefore, the ball is considered to be both a normal off-break and a doosra at the same time until it lands on the pitch and goes on to disturb the stumps.