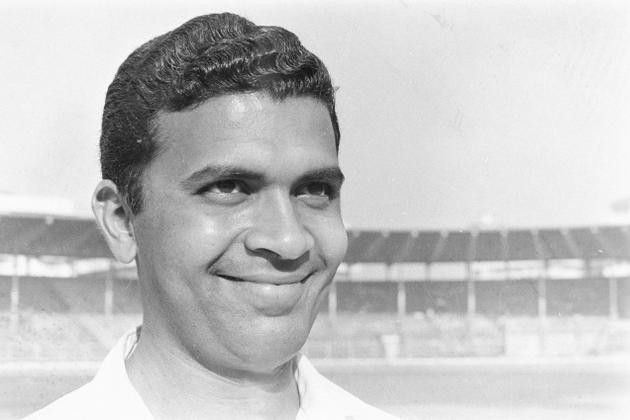

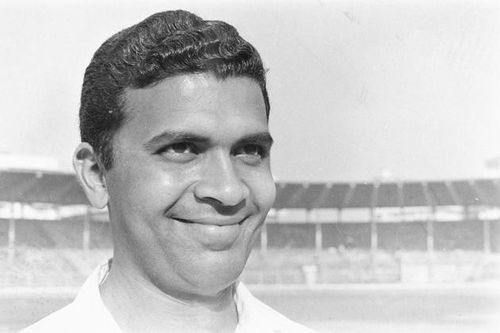

The Curious Case of India's Test opener Kenia Jayantilal

It was a quiet Sunday morning at Bombay Gymkhana, the ground where India had played its first test match way back in 1933 under Col C K Nayudu. My father was sitting alone at a table when an elderly man came to him and asked if he could join in; to which my father willingly obliged. The man sat down and said “My name is Jayantilal”. He told my father that he provides cricket coaching to children.

“I am that Jayantilal”

Trying to show his cricketing knowledge my father told him that long back there was a Jayantilal who was then touted as a competitor to the great Sunil Gavaskar but unfortunately got to play only one test for India. The man just smiled and replied “I am that Jayantilal.”

There was a moment of awkward silence and my father was embarrassed to say the least. This definitely was not the reply that my father would have expected even in his wildest of dreams.

Nor would have Kenia Jayantilal ever thought that his first test match would be his last match for the country. As Jayantilal once told in an interview to The Hindu “I never got another chance. It was frustrating for a while but I consider it was my fate.”

It indeed was fate. The series in question was India’s famous tour of the Caribbean in 1970-71. It was fate that an injury to Gavaskar before the first test had helped Jayantilal make his test debut for India. And it was also fate that despite being the third highest Indian scorer on the tour, he never got a second chance.

A Catch that ended a Career

As a result, Jayantilal’s name will not ring bells with even the keenest of cricket followers. Ironically the only noticeable place where I could find his name was in Gavaskar’s Sunny Days. Gavaskar writes “Jayantilal withdrew his bat at the last moment, but the ball came back sharply, got an edge and travelled like lightning between second and third slip. There was a flash of movement and Sobers came up laughing with the ball clutched to his chest. ‘What a catch!’ I told somebody. ‘Now all I want to see is Rohan Kanhai’s falling sweep shot, and my tour is made.”

Well the catch might have made Gavaskar’s tour in more than one way but unfortunately it ended Jayantilal’s career. Recalling the incident, Jyantilal said to an interview to The Hindu once “I was actually taking my bat away from the ball when it gained a nick and flew to Sobers. He had moved the wrong way when he stopped and came up with a diving catch. Of course it was a fantastic catch but it spelt doom for me”.

It is also interesting to note that during his first test century in the same series, Gavaskar was dropped by Sobers. If only Sobers had dropped Jayantilal and caught Gavaskar instead, I would have been writing on a different topic today.

There are few things which is beyond the comprehension of mortals and Jayantilal’s exclusion from subsequent Indian teams is one of those. Despite decent performance both on that Caribbean tour and in domestic cricket, he did not get a chance to wear the Indian cap again. Mind you India did not have a settled opening pair during those times. The only settled opener was Gavaskar himself and in fact the count of his opening partners over the years ran easily into double digits.

Jayantilal performed consistently in First-Class cricket

Jayantilal’s first class career had a dream start as he scored a century on his Ranji debut against Andhra Pradesh in 1968-69. Having started his first class career in 1967 for Hyderabad, Jayantilal continued to play domestic cricket till the late 1970s and finished his first class career with 8 centuries and 22 fifties in 91 matches. He was also the recipient of Indian Cricket Cricketer of the Year in 1971.

Put yourself in Jayantilal’s shoes and you will fail to disagree with his comment that he did not have a godfather. For, he had done everything possible to get a test recall. Reflecting back he said “I did not know who to go, what to do, since scoring runs also did not help”.

Today, he provides coaching to children who probably would never know about his unfortunate career. He seems to enjoy doing this and somewhere in his heart he would be praying that none of his wards have to go through his ordeal. In 2006 he had tried for the post of the Bombay coach but lost to Praveen Amre.

Like Jayantilal’s career, my father’s meeting with him was also short-lived and did not have a meaningful ending. And just like Jayantilal thinks it’s his responsibility to pass his cricketing knowledge to the next generation; I feel his is a story which should not get lost in the pantheon of great Indian cricketers.