Deconstructing the Virat Kohli cover drive

Cover drive. The purest shot in the game. The one shot that when played as per the book makes WG Grace rise from his tomb, give a solitary clap with his sodden palms, and ricochet back. The one shot that makes demons look divine and pain look pristine.

Virat Kohli is the finest shot maker in the game. He is the one man who could go to a bar with Shane Warne at midnight and come back sober. When he drives, he does it so smoothly, so sleekly, that you drop all that you're doing and gape at him for a second- a second worth a lifetime. If the cover drive is the art, Virat Kohli is the artist.

But what if we've been rhapsodising over a spoilt cake? What if the opera's been out of pitch, and we've been confusing it for trills? What if the finest cover driver of the world isn't exactly the finest?

The Virat Kohli cover drive is beautiful. It is a trivialisation of rules, of the binding reins that tie you to the obsessive pillar of zero bat-pad gaps and extensive follow-throughs. But it is beautiful because he plays that to a ball that most batsmen wouldn't dare to, in a way that most batsmen couldn't dream of.

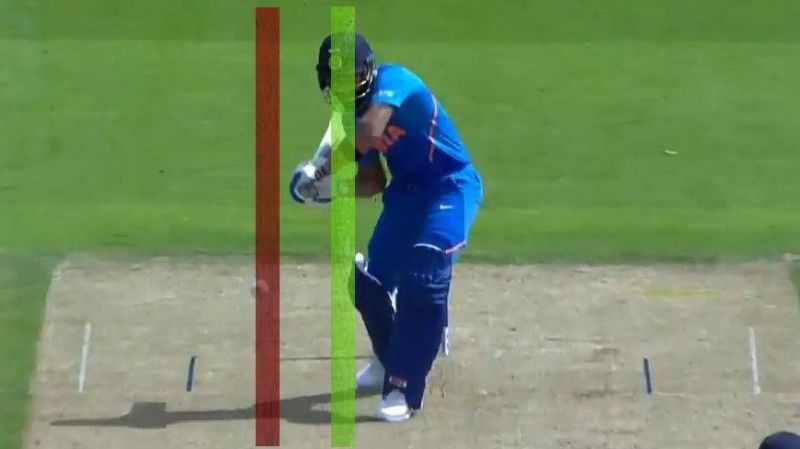

The average line of the ball that Virat Kohli drives to cover is way wider than the line for the average batsman.

One of the basic tenets of off-side play is that the wider the ball the squarer you play, or your coach sets you straight. Virat Kohli's cover drive is an unabashed thrashing of this rule. There is no ado, no follow-through, no sounds of calamity; he withdraws his bat from the ball in a sudden stutter of feet, like he doesn't care to pose for the cameras.

When you play a vertical-batted shot so far from the body, you're struggling to keep your bat straight. Your bat is always coming down at an angle, scooping the ball at places it shouldn't, diminishing your control over its latter half. You know where you want it to strike, but it gets impossible to meet the ball off the bat's sweet spot. You're always vulnerable to nicking off to the slips.

How often have bowlers tried exploiting this channel against Kohli? History suggests it hasn't been the worst idea.

In 2016, Trent Boult got Kohli caught at gully in consecutive games driving through the off side, and in 2017, Australia executed the same plan to perfection. And even in his greatest IPL season when he made four centuries, Zaheer Khan briefly managed to rekindle the ghosts of 2014, bowling into that fourth-stump line.

And don't fail to notice that a whole paragraph has been written without a word about James Anderson.

While Kohli averages 74.1 with the cover drive in international cricket, a lot of it is also due to his psychotic strike-rate of 189. Of the 45 batsmen with 300-plus runs with the cover drive since 2014, only Aiden Markram strikes faster than Kohli.

Like the night sky moon that looks so idyllic, the Kohli cover drive is also gnarled with craters, albeit looking perfect from the outside. This was exactly what Anderson exploited in 2014, when he didn't have a prominent back-and-across movement or the present version of his cover drive. Everything meant that Kohli played straight to balls that were supposed to be played square, for which on your worst days you'll have to pay a price.

His leap across these quandaries features the addition of three fascinating remedies to his game.

The changes in Virat Kohli's cover drive

The first of those is a very delayed trigger movement. Kohli waits for an eternity, until the bowler gets closest to his popping crease, for the minutest retrenchment of his back leg past the middle stump.

Depending on the format, he adjusts the openness of his stance. He also attains full control of his bat now, like he's sprung up from sleep, holding it firmer and straighter than before. His left leg rises in the air, pointing vaguely in the direction of cover, his entire body weight concentrated on his back foot.

When the ball is released, his front foot is still slightly in the air. This allows him to spring forward with all might, transferring his weight forward in a flash, making the positioning for a cover drive his impetuous second skin.

In a way, this is also the prompt behind his flick shot. The locus of his front foot as a result of his trigger, is just so ideal for the shot. He can plant his weight on it so freely and allow his mortar-like wrists to do the rest of the work. Kohli's game, when deconstructed, is heavily reliant on a few parameters.

The second is his head position. The 2014 Kohli didn't have a still head- one of the primary reasons behind his catharsis in the UK. The bat-tap through his trigger would contract his stance and cause the head to loll down, impeding his view of the bowler.

But despite being lambasted at the time by experts, he did not do away with it until the next overseas cycle. It was only in South Africa 2018 that he entirely committed to this new technique, suggesting that he preferred the bat-tap rather than playing without it.

The bat-tap still makes the odd appearance, but it has more to do with Kohli being comfortable with it. You can't banish for once and for all the technique you've made your own since the time you picked up a cricket bat. As Anderson called it, the dust of Indian pitches would not reveal any of its flaws. What he has done, effectively, is to shed comfort for results.

Kohli's third ingredient is more a gift than a quirk – extreme hand-eye coordination. Where his eyes want the hands to go, they race. The chemicals that travel across the synapses in his brain are incredibly strong, and their effect overwhelming.

A batsman with extraordinary hand-eye coordination will always survive, irrespective of technique. The wackiest batsman of our generation is ultimate proof of that. Smith's over-reliance on his hands have been emphasised enough, but what about Kohli's? With all the weird positions that he gets into, Smith is the last guy you'd expect to average 60 – but tell him that and he'll drawl a condescending 'mate'.

And so, even if this seems blasphemous to the avalanche of Indian fans out there, allow me to say – Kohli's game is as susceptible to age as Smith's.

Even if he's the fittest and the hungriest. His cover drives are. And if an overwhelming 18% of his runs in international cricket come off the cover drive, it is certainly valid to extrapolate that his game does stand a chance of deteriorating in the coming years.

This is not to give you a panic attack or to give Tendulkar and Ponting elite company. This is just to emphasise that we selectively steer clear of certain things. We might have seen the last of Kohli versus Anderson, but the Indian captain will never run out of doubters to prove wrong. The better he is, the more they will be in number, and they will be in and around him.

Kohli's career today is at another fork. And perhaps his retort make all the difference. He could be the poet's moon – a reader's delight, the metaphor for all the great little things of the world. Or, he could be the astronaut's moon – the knotty flotsam gnarled with craters.