Dissecting a 'good-length' delivery in cricket

India vs South Africa. Cape-Town. Third ODI. 2006.

0.1, Zaheer Khan, left-arm over, runs into bowl, with South Africa’s skipper Graeme Smith on strike. Zaheer pitches it slightly short of good length, shaping it in a touch. An uncertain Smith tepidly comes forward, as the ball wraps onto his front pad. India appeal for a leg-before, but the umpire dismisses the appeal, indicating the ball might have just gone over the top of the stumps.

0.2, This time, Zaheer pitches it just a bit further up on a good length, swinging it in. Smith, again, tries to play a half-hearted drive, but the ball sneaks between bat and pad and crashes onto the off-stump.

Jacques Kallis walks in next to bat.

0.3, Zaheer angles this across the right-handed Kallis, who looks hesitant whether to play or leave it, but decides to shoulder arms to it.

Up till that moment, Zaheer Khan had bowled three perfect deliveries around the good length area. Ideally, Kallis would have been expecting another similar delivery.

0.4, On this occasion, Zaheer surprises Kallis by bowling one full and wide. Kallis, out of instinct, goes for big swish but gets a nick to Sachin Tendulkar at first slip.

Zaheer follows it up with two more dot deliveries to Herschelle Gibbs, ending with a double-wicket maiden.

This over by Zaheer was the perfect manifestation of intelligent good length bowling by a fast bowler. Zaheer bowled five out of the six balls on a good length, leaving the South African top order clueless. So, what made Zaheer so effective in the over? What is the mystery behind batsmen being unable to negotiate a ball that lands on the good-length area? And finally, what is a good length delivery?

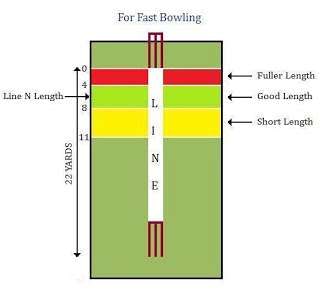

The answer is pretty simple, actually. A ball is termed as a ‘good-length delivery’ when it leaves the batsman in two minds, on whether he should go forward or back. Modern computer analysis reveals that a delivery pitched at a distance somewhere between 4-7 metres (4.3-7.7 yards), is considered to be at a good length. But this measurement is not definitive and is subject to various pitch conditions, such as the bounce on the wicket. To put into perspective the criticality of different conditions affecting the calculation of the ‘good length’ area, it is important to look at good lengths on different surfaces across the world.

The match described above was played at Cape-Town, where the wicket is known to have good bounce. Zaheer’s first delivery hit Smith on the pads, but the umpire signalled that it would have probably gone over the stumps. If Zaheer had bowled the same delivery at Chinnaswamy Stadium in Bangalore, where the wicket is known to possess moderate bounce, it would have definitely crashed on the middle-stump. This is how a good length varies across venues.

On a surface, where the pitch is known to produce average bounce, a distance of close to 7 metres from the batsman would keep batsman guessing about whether to go front or back. On the other hand, on a surface generating sharp bounce (such as the WACA in Perth), the good length delivery will be closer to the batsman, pitching at a distance of nearly 4 metres from the batsman.

But why is this distance of 4-7 metres so critical? The answer is very well documented in most batting manuals. For a batsman to deal with a full-length delivery, it is crucial for him to lean forward to get his front-foot as close to the ball as possible. Similarly, to negotiate with a short delivery, a batsman must transfer his weight on his back leg, and stay upright to either cut or pull the delivery.

So when the ball is pitched in areas where a batsman can do neither of those two things, he gets caught in two minds. That what makes a ‘good-length’ delivery so difficult to score runs to.

Corridor of uncertainty

We have often seen the commentators use the expression ‘corridor of uncertainty’ during the matches. It’s often used when a fast bowler flummoxes a batsman beating him completely, or getting the outside edge of his bat. But how do we know that a delivery was bowled at the corridor of uncertainty?

The first step to bowling in the corridor of uncertainty is to pitch the ball on the good length region, which is specified above in the article. But bowling at a good length is only half the job done. The other half is the line of the delivery. It’s only when the ball is delivered on a narrow line, on or just outside the batsman’s off stump, that it can be considered bowled at the corridor of uncertainty.

When bowled at this length, not only does the batsman has to ascertain whether to go front or back, he also has to make the decision whether to play the ball, or to shoulder arms to it. If a batsman leaves the ball, there's a chance the ball will either bowl him or hit him with an increased chance of leg before wicket. If a batsman plays the ball, there's a chance the ball might lead to an outside edge that can be easily caught.

This task can be demanding for even the best of the batsmen, and don’t forget, I still haven’t mentioned factors like swing (conventional and reverse) and speed yet. Bowling at this line and length can be lethal weapon against a batsman who has just walked out to bat, as Smith found out during the over by Zaheer. Bowling at the corridor of uncertainty can also be a brilliant way to set-up a batsman’s dismissal, which brings me to my next point.

A good-length delivery early on can unsettle the batsman

In his third ball in the over and the first to Kallis, Zaheer delivered it at a good-length region, angling it across Kallis. The line and length would have put Kallis in two minds for a fraction of a second, which he finally decided to let it go. Given the previous two deliveries to Smith were delivered at the same length, Kallis would have been expecting a similar ball. His mind would have been devising ways to counter another out-swinging good-length delivery.

And that’s where Zaheer tricked Kallis. He deceived him at mind-games, and bowled a next ball full, and wide outside the off-stump. Kallis, eyeing for it to pitch on good-length, out of instinct went for a wayward drive, nicking the ball to Tendulkar at first slip, becoming Zaheer’s second victim in the over.

Here’s the video of some fine bowling by Zaheer:

Bowling good-lengths consistently is an art that only a few bowlers have been able to achieve. Glenn McGrath was a master at bowling this nagging line six times in an over, something that made him an all-time great. Out of the recent lot, Dale Steyn has been able to achieve significant success in bowling immaculate lengths, coupled with fierce pace. Amongst the Indians, Zaheer Khan was a great exponent of making the ball swing along with pitch-perfect lines, especially to left-handed batsmen.

It will be interesting to see who amongst the current crop of fast bowlers goes onto to attain mastery over this hallowed art of ‘good-length’ bowling in cricket.