When teenaged Don Bradman first crossed swords with another legend-in-waiting, leg-spinner Bill O’Reilly

No one would have realised that the seeds of the Don Bradman legend were sown when the New South Wales town Bowral's cricket team took on the neighbouring Wingello team in the season of 1925-26.

It was a home fixture for Bowral in the Berrima District (Southern Tablelands) cricket competition, played on a Saturday afternoon. Wingello, if anything, was an even smaller country town than Bowral.

The yardstick to decide such things in those days was quite simple, and Bowral had conclusive evidence in its favour. It boasted of three pubs while Wingello, which was further into the outback, had none.

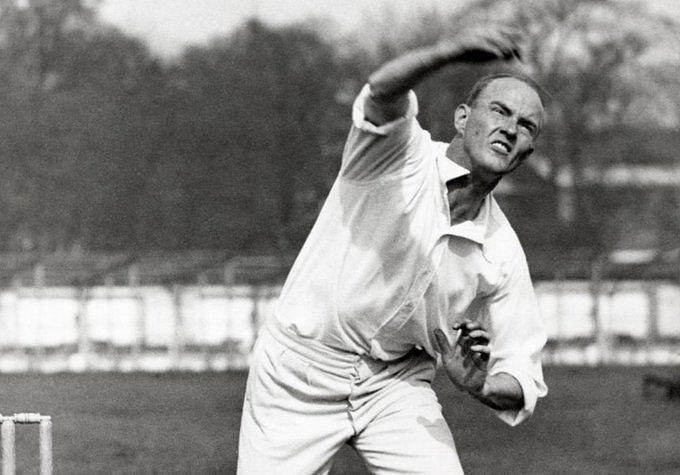

Seated in a train pulling into Bowral station just before the start of the match was a yet unheralded undergraduate from Sydney University who answered to the name Bill O’Reilly.

The young man, contemplating a quiet weekend at his railside home at Wingello, was shaken from his reverie by frantic calls for him from the platform outside at Bowral.

It was the voice of the Wingello station master, who was also the captain of the sleepy little hamlet’s cricket team. The Wingello skipper had taken care enough to fetch the budding leg-spinner’s cricket gear from his home. He then hauled his prized 11th man from the train to the Bowral ground.

It is sometimes providence that has a hand in the blooming of great careers. If Don Bradman’s stint with Bowral had begun because a player did not turn up, O’Reilly turned out now for Wingello because they had nobody else. For different reasons, each was filling up one last vacancy.

And so the two faced up to each other. Who could have imagined then that both would become masters of their craft, the best in the world, and that the nondescript ground would become famous as the Sir Donald Bradman Oval?

Bowral won the toss and batted on what was at that time, a hard concrete pitch topped with matting.

Don Bradman shows shades of greatness very early

This is a story recounted by O’Reilly himself, and more than five decades later, he reminisced in an article in The Hindu:

“Perhaps to get full value from the trouble he had taken on my behalf earlier in the day, my station master and captain handed me the new ball. I got a wicket quickly - nice going.”

O’Reilly continued:

“It was pleasantly reassuring to see the replacement batsman making his snail-paced diffident approach from the shade of the age-old gum tree which served as the shelter shed. This had all the signs of an easy job. How was I to know that I was about to cross swords with the greatest cricketer that ever set foot on a cricket field.”

O’Reilly had the better of the early exchanges with Don Bradman, then 17-years-old, and may have even bagged his wicket on a couple of occasions. But once the Don settled down, he launched a stupendous attack on the hapless trundlers, or at least that is what they looked.

When the day was done, Don Bradman was unbeaten on 234 and O’Reilly had realised that hopping off that train had been “a very grave tactical blunder.” As the game was to resume the following Saturday afternoon, O’Reilly had enough time to grieve.

He would not have fretted, though, if he had known, at that nascent stage of his career, that this game can indeed be a great leveller.

On resumption, O’Reilly bowled Bradman first ball,

“with a leg-break which came from the leg-stump to hit the off bail. Suddenly cricket was the best game in the whole wide world.”

One of the balls of the century had been bowled in this then-obscure settlement several decades before a frenzied media marked out another much-celebrated delivery in 1993 as the ball of the century!

With his first-hand knowledge, this was one of the main reasons why Bradman anointed O’Reilly as the greatest-ever leg-spinner. It is but one example of a couple of talented lads from remote little towns going on to be counted amongst the most famous names sport has ever known.

(Excerpt from Indra Vikram Singh’s book ‘Don’s Century’).