Four Ways to Re-invigorate the One Day International (ODI) Format

I have been a staunch defender of cricket’s One Day International (ODI) format for many years. The 50-over format still has a lot to offer for the average cricket fan. It acts as the mid-way point between Test cricket’s five-day ebbs and flows and the frenetic nature of T20s.

Of late, however, the format has unfortunately begun to stagnate. Once the chief money maker in cricket, its prominence has slowly diminished. The protracted tri-nation ODI competitions and the 5-7 match bilateral series of yesteryear have largely disappeared.

Nowadays, international tours are mostly played in sets of three – three Tests, three ODIs and three T20Is. This is not a bad thing by any means, as it offers cricket fans plenty of variety. But global T20 franchise leagues have emerged splendidly and there has been a resurgence of bowler-friendly pitches. Add to that, outright results in Test cricket, and the ODI format desperately needs a bit of sprucing up.

With that in mind, here are four ways how the ODI format can be revitalized:

1) Make the white ball of ODI swing

Post the 2015 ODI World Cup, the Kookaburra white ball has lost a lot of its early overs swing. Opinions differ as to the exact cause, but there is little doubt regarding the white ball’s dwindling wicket taking potency. This is despite the use of two new balls; which theoretically should prolong the ball’s period of swing during the ODI Powerplay overs.

An ESPNcricinfo article from 2018 attributes the vagaries of swing to the ball’s method of construction. In the Kookaburra balls, only the middle two rows of seam are stitched across both halves of the ball. In SG and Dukes balls, all rows pass through both halves.

This produces a flatter seam in the Kookaburra balls, causing it to lose its swing and shape early. This is especially problematic due to Kookaburra’s white ball market dominance and exclusive usage for ICC events.

For ODI cricket to endure and flourish, a genuine balance between bat and ball needs to be maintained. It is crucial that swing bowlers don’t go the way of the dodo and still have their place in the game.

Perhaps the outlook is not as gloomy as feared, as the 2019 ODI World Cup showed. Rather than the predicted 50 over slogathons on flat pitches, we witnessed the ball swinging and thrilling, low scoring games, best epitomized by the dramatic final. It made for some truly engaging contests despite the elongated competition format.

According to New Zealand's left-arm swing bowler Trent Boult, it was all down to the glossier finish of the lacquer, similar to the newly introduced pink ball. This is something that needs to be studied extensively and could hold one of the keys to the future survival of ODIs.

2) Bring back reverse swing

Starting 2011, ICC’s adoption of the two new-balls rule has effectively killed reverse swing in ODIs. It is the lost art of bowling that desperately needs to be brought back. The idea has many high-profile backers such as Sachin Tendulkar, Harbhajan Singh and Waqar Younis.

Ironically, the rule became a necessity in the first place due to the shortcomings of the Kookaburra white ball. Over the course of 50 overs, it would routinely get discoloured and thus had to be replaced in the later stages of the innings at the umpire’s discretion.

In 2007, the ICC tried to standardize the process by making the ball change mandatory after the 34th over. But this also had its drawbacks. If the ball was too hard and new, batsmen would make merry in the death overs. If the ball was too worn out, it would reverse and bowlers would get a bag full of wickets.

So the two new-balls rule was finally brought in to stop this inconsistency. Surprisingly, the ICC never trialed or experimented with other brands, despite Dukes’ and SG’s claims about the superior durability of their white balls. These balls could apparently make it through an entire ODI innings without discolouration or losing shape.

These assertions need to be investigated. If found to be true, the adoption of alternative white balls should be seriously considered for one-day cricket.

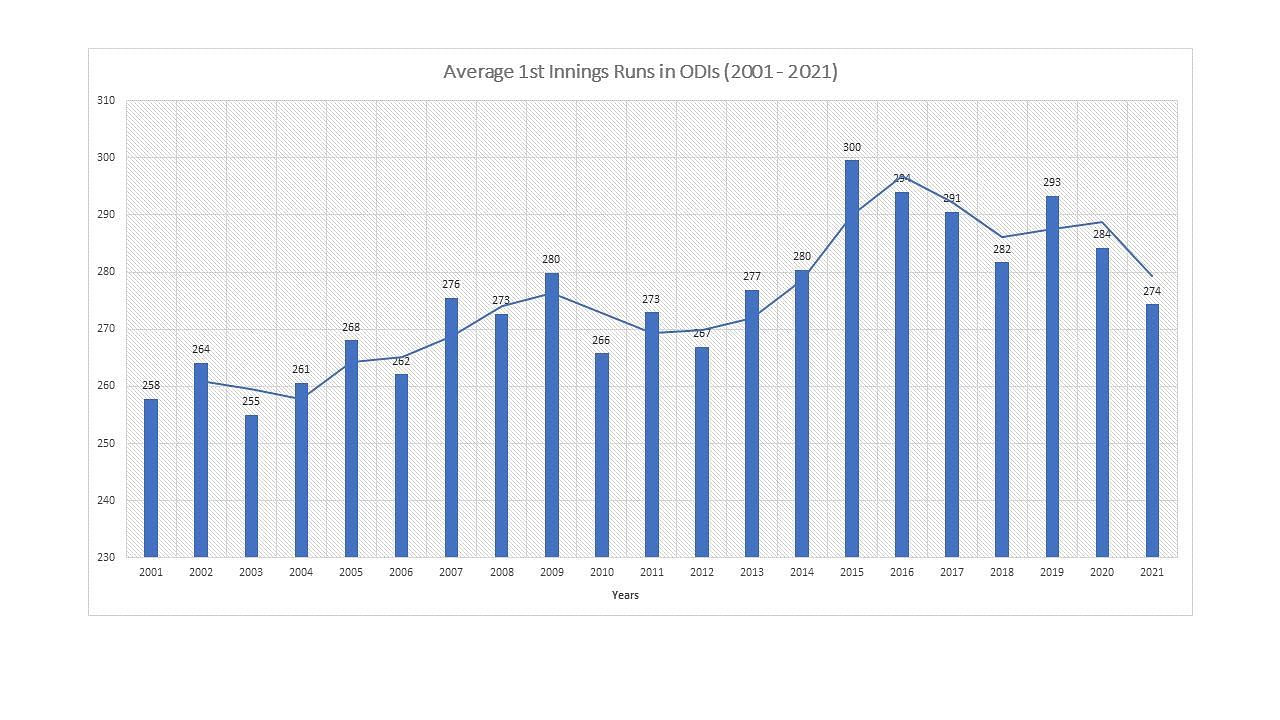

The above graph shows how average first innings scores in ODIs have increased markedly over the last two decades. The first noticeable spike occurred after the introduction of the batting powerplay in 2005; although with reverse swing still in play, the increase was gradual.

Since the adoption of the two new-balls rule in 2011 and the subsequent death of reverse swing, average first innings scores have gone through the roof. 300 became a par score in 2015.

Concerned about the rising imbalance between bat and ball, ICC ditched the batting powerplay. They allowed one extra fielder outside the circle in the last 10 overs, starting late 2015. These measures have provided some relief to bowlers (as evidenced by the slight downward trend since 2016), but much more needs to be done in this regard.

3) Make more sporting pitches

Despite a less than ideal competitive structure, the ODI World Cup in 2019 had plenty of exciting games and a stirring denouement. This was mainly down to the swing on offer and due to the sporting nature of the pitches. It provided some assistance to bowlers, and barring a few exceptions, prevented the games from becoming a simple exercise in slogging.

Speaking to cricket.com.au, Justin Langer summarized the problem with flat pitches quite eloquently.

“I see flat pitches as a huge problem for the health of cricket. I’ve said this for 10, 15 or 20 years, for the health of Test cricket, first-class cricket and even one-day cricket, you want to play on wickets where there’s a contest between bat and ball. When there's wickets falling and the best batsmen score runs, that's great Test cricket or great one-day cricket for me,” he said.

I cannot agree more with Langer. Watching a cavalcade of big hits, 360-degree slogging and balls sailing over the ropes for 20 overs is one thing. However, it quickly becomes tedious and monotonous when repeated over 50 overs.

The ideal pitch should reward good batting but also aid pacers and/or spinners. As with many things, variety is indeed the spice of life. One Day internationals need to maintain a clear distinction between both the Test and T20 formats to be a viable product.

4) Don’t scrap the ODI Super League

Scrapping the ODI Super League after just one cycle has been a completely regressive move by the ICC Chief Executives Committee (CEC). The Super League concept added value, context and meaning to bilateral games. It crucially provided lower-ranked full members and top performing Associate nations with regular fixtures against cricket’s big boys.

Additionally, it made the World Cup qualification process fairer with Full Members having to qualify based on their performance rather than status or rankings. It offered a clear pathway to Associates.

The ICC needs to be held accountable and ultimately, they need to answer the following questions: How is such a system fair by any metric? How are the lower ranked teams expected to improve without proper exposure to 140 km/h+ pace or quality spin bowling?