How the dynamics of wicket-keeping have changed over the years

A cricket team of 11 players will have some batsmen, bowlers, all-rounders (maybe) and a wicketkeeper. The count of batsmen/bowlers/all-rounders may change depending on pitch condition, opposition strengths or weaknesses, individual performance and team balance but there will always be a wicket-keeper.

The criterion to identify a good batsmen or bowler has not changed significantly with the advent of new cricketing techniques.

For example, in a T20, if a batsman can chip in a quick thirty (strike rate of 150-200), he would be considered a better option than a player with a 50 against his name but at strike-rate of 110-120.

Nonetheless, the crucial factors determining if a bowler or batsman is good or not are still the same.

However, for a wicketkeeper, the desired skills have changed with the course of time. Historically, wicketkeepers in test cricket were judged by how well they kept wicket; their batting skills were useful, but their place in the team didn't depend on it.

As per Sir Donald Bradman, the greatest wicketkeeper of all times is Donald Tallon. He was quite a deft wicket-keeper and his batting average of 17 was never a point of discussion.

During those days, an average in the mid-20s, or even lower, was acceptable. Most of the better wicketkeepers had average batting skills but they were all outstanding behind the stumps. Due to these niche skills, they enjoyed long careers.

Rod Marsh played 96 Tests and scored only three hundreds with a career average of 26.51; for Wasim Bari, it was only 15.88 in 81 matches, and England's Bob Taylor averaged 16.28 in 57.

West Indian Desmond Lewis started his career with scores of an unbeaten 81, 88, 14, 72, etc. and though it would seem that these were good enough stats to secure his place in the team, yet Lewis was soon replaced by the superior gloveman Deryck Murray.

Statistically, Lewis is the best wicketkeeper-batsman of all time with an average of 86.33 over 3 test matches.

Jeff Dujon and Alan Knott had a career average marginally above 30 but it was their spectacular wicket-keeping skills which would earn them a place in the squad. For Dujon it was the flexibility and athletics whereas for Knott it was how nimbly he would collect the ball facing some of the best bowlers in the world.

Even for India, in his short 4 year and 14 match tests career, Khokhan Sen impressed everyone with his dexterity by conceding just four byes when the hosts piled up 575 in India tour of Australia in 1947. Sen's finest moment came against England in 1951-52 in Madras, where he affected five stumpings – of which four were in the first innings - off Vinoo Mankad's bowling as India took their first Test victory.

Farokh Engineer and Syed Kirmani were amazing batsmen but what guaranteed their place in the squad was their sharp reflex and agility against the bowling of legendary spinners of the time. The way both of them countered the established bowlers, earned them the respect of the cricket community worldwide.

The only aberration to this trend was Les Ames. It was said there were better wicketkeepers than Ames and that he was in the England team because of his batting. With a career span of 47 test matches, he scored 2,434 runs at an average of 40.56 and took 74 catches and affected 23 stumpings.

By 80’s these were amongst the best wicket keepers the world had seen. However, the requisite skills for wicket keeping were expected to change soon and the initiator of this was none other than the country which invented cricket. During the early 90’s England's insistence on picking wicketkeeper-batsmen limited Jack Russell’s international career.

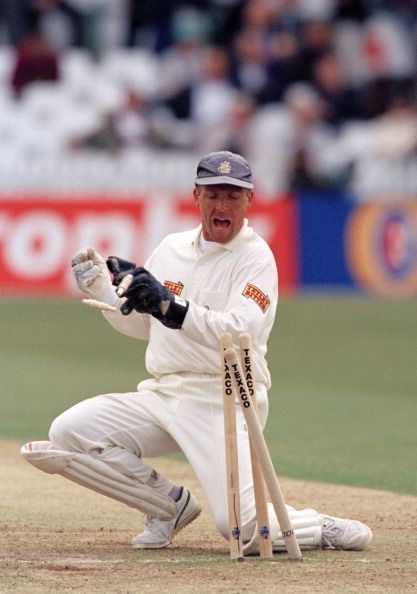

His 11 dismissals in Johannesburg in 1995-96 set a world record. He played in 54 Tests, making 165 dismissals but eventually lost the place to Alec Stewart. Russell’s own batting wasn't too shabby; he hit two Test hundreds, and his four-hour 29 not out in that Johannesburg Test was often forgotten.

Alec Stewart was a crafty opening batsman and provided strength to England batting line up.

On similar lines, the Australian cricket board decided to replace Ian Healy with Adam Gilchrist. Healy had a significant contribution to Australia's resurgence in the late 1980s and 1990s. A wicketkeeper of the highest quality, not to mention the finesse of handling Shane Warne’s sharp spinning deliveries, Healy was also a fiercely irritating counter attacker at No. 7. He made it to the team of the century named by the Australian board.

With an average of over 50, in a 63-Test career, Andy Flower is amongst the best wicketkeeper-batsmen in the world. Although he appeared on the international scene much before Adam Gilchrist, his efforts are sometimes unnoticed by many as he was part of the team which hardly ever won.

In those days of late 1990s, the Indian Cricket Board was plagued by the problem of finding a suitable wicketkeeper who was also a competent batsman and Saba Karim seemed to fit the bill. He broke into one day cricket when he scored a fast half century against a formidable South African opposition in 1996. He was an accomplished player who was as adept at his batting skills as he was at wicket-keeping.

However, his career was cut short by then-rising star Kumble’s deadly delivery in the Asia Cup in Dhaka. That ball struck him on the right eye off the batsman’s boot. The injury thus ended Karim’s career and propelled India into a struggle of another 5 years in search of a formidable wicket keeper until the discovery of Mahendra Singh Dhoni.

On the other hand, South Africa stuck to Mark Boucher. He was often overshadowed by the spectacular run-scoring feats of his contemporaries, Andy Flower and Adam Gilchrist, but he still holds the record for most Test dismissals by a keeper, the number being pegged at 555. He was the first keeper to take 500 Test catches.

Boucher seamlessly replaced Dave Richardson in 1997-98 and played a key role in the team, in both formats. He overtook Ian Healy as the leading wicketkeeper in October 2007. He was a very useful batsman, made five Test hundreds and could pack a punch when needed.

In their eternal quest for a wicket keeper-batsman, many countries converted their batsmen into wicket keepers. A brilliant example of this strategy is Rahul Dravid who gratefully upheld this responsibility until finally transferring it to Dhoni’s able shoulders.

For South Africa, it was a tough task because of the poor planning that preceded it. Even as Boucher's form dipped, no clear attempts were made to identify or groom a successor. Thus the future of South African cricket was handed the additional responsibilities of wicket keeping.

AB de Villiers has admitted that he was overburdened by his roles as a batsman, wicket-keeper and part of South Africa's leadership core. However, South Africa now seems to have found a tremendous wicketkeeper-batsman in the form of Quinton De-Kock.

Thus it looked quite obvious that every team would have a specialist wicket keeper batsmen in their team and for those who don't, there would be plans to produce one.

However Indian selectors turned the tables when they selected Wriddhiman Saha as reserve wicket-keeper ahead of standard Dinesh Karthik during the 2010 South Africa tour. As long as Dhoni was around, Saha wouldn't get a chance but whenever he got a chance, he grabbed it with both hands.

Saha was one of the 16 member squad which made the flight to the Australia in 2011/12 and played in Adelaide when Dhoni missed the game following an over-rate ban. He impressed everyone with his neat work behind the stumps.

After Dhoni's retirement, selectors had multiple options to choose from the likes of Parthiv Patel, Robin Uthappa, Dinesh Karthik and emerging young talent such as Sanju Samson and Rishabh Pant but they choose to stuck with Saha. Many of these are better batsmen than Saha but technically the Bengal wicketkeeper is almost flawless and his athleticism and agility are what make him better than the rest.

It would be interesting to see if other boards follow a similar path and just like it was in the past, would glove-work and flexibility gain priority over batting skills during the team selections.