India vs Pakistan: Why sports should triumph over politics

The word rivalry in cricket sires only one notion to all and sundry – India vs Pakistan. The English and the Aussies might disagree, for they oxygenate the 2nd longest, extant rivalry in cricket – the Ashes. However, a cursory appraisal would lay bare the fact that the Ashes is merely a tradition, whereas the battle between the two nations sitting astride the Indus river is more of a war fought with willow, leather and of course, a lot of adrenaline! There is no contest in cricket that would even make neutral fans savour it viscerally other than the epic clash between India and Pakistan.

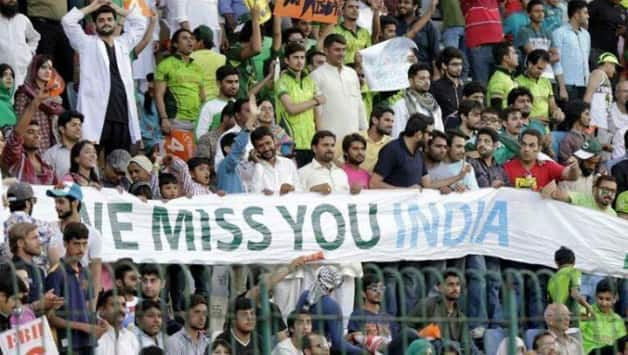

Honoring their rivalry, Australia and England face each other often. On the other hand, India and Pakistan locked horns in a bilateral ODI series nearly three years ago and they have not played a test series for eight years. But such is the gravity of the battle between these two countries, the long wait for a resumption has only fuelled the expectancy profoundly.

As a relief for the cricket fans world over, in 2014 ICC confirmed that India and Pakistan would be facing each other in a bilateral series in December 2015. But thanks to heinous politics, nationalism and communalism, the series is unlikely to proceed.

Political turmoil and combats in the border had previously interrupted the rivalry. But India’s tour of Pakistan in 2004 and Pakistan’s tour of India in 2007/8 yielded a semblance of cricket trouncing any political enmity, but with the Mumbai attack in 2008, it was proved to be ephemeral.

Things started to look rosy as Pakistan toured India for a three-match ODI series in 2012 but the current surge in anti-Pakistani sentiments among certain vigilante mobs and political groups in India have made sure that it would remain the last bilateral series between the two nations, at least for some time.

With ICC pulling back Aleem Dar from officiating in the ODI between India and South Africa in Mumbai, and the eventual volunteered withdrawal of Wasim Akram and Shoaib Akthar from the commentary crew citing security concerns, it is safe to surmise that the sport of gentlemen has been vanquished by noxious politics.

Sports can unite worlds

But is there any scintilla of fairness in halting a sporting contest for political problems? Since time immemorial, sports has shown they have the power to heal a society.

Cricket’s role in pacifying political tensions has been even more emphatic. Kumar Sangakkara in his much acclaimed MCC lecture in 2011 asserted how cricket in Sri Lanka helped the islanders heal the wounds of a 30 year war.

“The 1996 World Cup gave all Sri Lankans a commonality, one point of collective joy and ambition that gave a divided society true national identity and was to be the panacea that healed all social evils and would stand the country in good stead through terrible natural disasters and a tragic civil war.

The 1996 World Cup win inspired people to look at their country differently. The sport overwhelmed terrorism and political strife; it provided something that everyone held dear to their hearts and helped normal people get through their lives.

Regardless of war, here we were playing together. The Sri Lanka team became a harmonising factor.”

Sports transcend all contrived bounds that have forever kept humanity splintered, resulting in intra-species confrontations that have engendered futile loss of lives and properties alike. “Sport can unite worlds, tear down walls, and transcend race, the past, and all probability”, wrote Shehan Karunathilaka in his award winning novel woven around cricket, Chinaman.

George Headley, who played cricket for the West Indies in 1930s and was known as the Black Bradman, was a beacon of hope for the down and out blacks of Jamaica, making them believe they too can reach greater heights despite the then popular belief that the colored Africans were inane.

Very recently, Cristiano Ronaldo led a Syrian refugee kid, whose father was tripped by a camerawoman while carrying him in Hungary, into the Santiago Bernabeu stadium in support of the Syrian refugees arriving in Europe.

Cricket shows the way

In fact, one doesn’t need to look too far from India and Pakistan to realize how sports can be a palanquin that conveys hope and optimism. When LTTE, a terrorist organization, exploded the Central Bank of Sri Lanka in Colombo just months before the 1996 world cup, scaring both Australia and West Indies into forfeiting the World Cup matches in Sri Lanka, India and Pakistan sent a combined XI to Sri Lanka to play an ODI against the home side.

Although India and Pakistan had not played against each other since 1989/90, the two rivals played together in a combined XI for the first time. It was a brotherhood – a region’s collective realization of its strength as a single dominion – fashioned to send the rest of the world a strong message.

“As far as the game is concerned we are all together. We have come to Sri Lanka to make sure that it is going to be a very successful day today. I hope everyone realizes that there is nothing wrong where sport is concerned”, declared the captain of the side Mohammed Azharuddin.

Perhaps, the best of the many examples, would be how the Pakistani president General Zia-ul-Haq visited India, to attend a test match between India and Pakistan in order to abate the tensions that arose between the two governments following the Soviet’s invasion of Afghanistan.

Such cricket diplomacy has helped both countries fend off war clouds for a very long time. Cricket has been the pretext using which both countries attempted to re-establish their diplomatic relationships.

Pervez Musharaf, the former head of Pakistan, once stated that cricket could be the “ice-breaker” when the two governments are not in touch with each other for a very long time. Cricket has left trails of peace wherever it travelled and, who knows, cometh the bilateral series between India and Pakistan, cometh the resumption of diplomatic relations.

World Cups have brought ceasefires even in the middle of intensely fought battles in Sri Lanka, and if there is one thing that can appease the tension between the neighbours, then it has to be cricket.

Do people really care about the political differences in their daily life?

Despite the occasional rallying behind their nations, Indians and Pakistanis seem not to care about the political differences. The many wars fought between the nations do not appear to have distracted Pakistanis from admiring Shah Rukh Khan, nor have they dissuaded Indians from throwing themselves at Fawad Khan.

In the face of the ruthlessly fought cricket matches between India and Pakistan, Indians reserve great respect for Pakistani players as much as Pakistanis have for their Indian counterparts. There cannot be a better example to underpin this fact than the Chennai crowd applauding the Pakistani players, after they emerged victorious in a hard-fought test match between India and Pakistan in 1999.

The way the plight of Geeta, an Indian woman who was stranded in Pakistan and was taken care of by a Pakistani shelter home, was treated by the Indian and Pakistani populace and how Indians made use of the Indo-Pak series in Pakistan in 1978 to visit their old friends and kin across the border clearly show that nothing, even politics and nationalism could trump ordinary human beings’ predisposition for camaraderie.

Tears, sentiments, love, emotions and all the other immortal characteristic features of the mortals transcend all man-made segregations. There are things in life which politics cannot dictate terms on – things where humanity holds sway.

Sporting contests, much like love is a sheer expression of humanity’s innate penchant for association and companionship. When genuine cricket fans want a contest to savor, what right does politics have, to stop people from having fun?

What happens in the border has no significance in cricket

Come what may, Misbah-ul-Haq or Yasir Shah cannot be held accountable for what Pakistani army does in the border or what Pakistani-born terrorists do within India. Neither cricketers nor cricket has anything to do with the ugly skirmish between two power mongrels.

Let the hideous squabbles and heinous infiltrations be reserved to the governments and the armed groups. Let the ordinary people, seek ordinary pleasures surpassing all bounds instead of extolling martyrdom and embracing violence, for what most men and women need is good food and great fun.

Hatred and enmity should be confined exclusively to those who derive sadistic pleasure in hurling grenades and listening to the cadence of the ballistic missiles and the squalls of the bereaved. Let the music of the willows and the flinging of the leather regale everyone else.

Cricket between these estranged countries could help heal the wounds of the horrific past. But above all, what is important is that the cricketing world should send the world a strong message, about its unity and about its solidarity. The cricketing world should be singular sans ethnic, racial, linguistic, religious and political differences.

Cricket fans should identify themselves as a single nation, as a community that thrives in the values the virtuous game of ours has taught us. Indian and Pakistani government might not want to end their skirmish, but Indian cricket and Pakistani cricket should always find solace in each other’s arms and show that sports can indeed heal scars and unite nations.