Is cricket going soft?

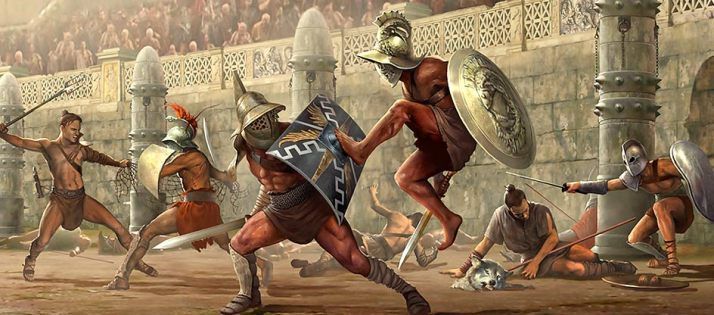

I recently had the opportunity to visit Rome’s Colosseum. Standing in the centre of the dilapidated stadium, I closed my eyes and pictured a life two thousand years prior to my own. As history’s jigsaw puzzle put itself together in my imagination, the sights, sounds and smells of a reality more primal than life today.

As the Polaroid camera of my fantastical journey blurred into existence, I saw a crowd of fifty thousand strong in the legendary arena. Romans of all backgrounds, clothed in pristine white garb, bayed and howled at the action. Adrenaline rushed through my veins as my mind's eye turned to the Emperor, sitting fat and content in one end of the amphitheater. He, too, with all his laurels and loyal servants, was transfixed by the action.

Men fought other men, but not without purpose. Free of advertising, free of sponsorship, free of endorsements – it was a competition all about freedom, the fighters’ freedom. Every match was fought to the death, to win was to live to fight another day and the spectators could not get enough.

The stench of death hung low and thick in the air but with it, I smelt the trepidation of competition, the rich aroma of sportsmanship. As I came back to my touristy reality, I thought about the sport I loved and its dalliances with danger and adversity. Is cricket missing some sort of animalistic aggression?

***

Most popular sports around the world allow physical contact to a degree. Football, both American and regular, Rugby, Basketball, Boxing and Ice Hockey all invoke the human love of violence to good effect, roping fans in by the thousand for the battle of physical strength of the contest.

Cricket does not do that. It would not have been so successful in the colonies if it did. Around the time England were off conquering strange and foreign lands, cricket’s popularity in Britain soared. As a result, every army regiment had its own cricket team and holding fort abroad meant they had little to do when the ‘uncivilised natives’ were behaving themselves.

Over time, they realised that cricket was the perfect game for the social elite of these strange lands to participate in alongside their British masters. Without contact, there was no need to touch the lowly locals. Because of this lack of physicality, cricket thrived in the colonies in places like India and the West Indies, where locals were treated with little dignity.

In Mumbai, a quadrangular tournament between Parsis, the British, the Hindu elite and the Muslim elite prospered, a clear indicator that cricket was a sport that could only succeed if its participants did not get into physical altercations. And it has remained that way in the subcontinent and Africa, through independence struggles and freedom movements.

Which is strange if you think about it. Revolutions are born out of blood, sweat and tears and one would think that a country’s cricket, too, follows in that country’s proud tradition to fight, either with sticks and stones or peaceful protests. One would think that cricket would imbibe the hardness of struggle, the defiant nature of people doing whatever they could to survive. One would imagine that the sport that draws so many parallels to life, would embrace the historical fight of two billion people, of every colour, religion and cultural background instead of shying away from it.

Is it that the custodians of the game, who for the longest time were the MCC – a traditionally English organisation – actively tried to oppress that side of the game, in its pursuit to maintain the ideals of the ‘gentleman’s game’? Is Test cricket exactly what they all say it is – a boring sport? Or is cricket a hard game with hard rules played by hard men, whose fight is just different to the fight we see on UFC or football or wrestling?

This identity crisis is what plagues the game today, and till Test cricket figures out what type of sport it wants to be, it will become a social pariah, left out in the cold by administrators, broadcasters and even the fans.

The issue stems from the fact that administrators, both at a first class and a Test level, are obsessed with catering the game to the upper-middle-class and as a result, they think that allowing the sport to pander to raw human emotion would alienate their bourgie base. Which is why cricket nowadays is littered with unnecessary legislature that impedes players expressing themselves.

September 2016, the ICC’s new demerit point structure came into being. This structure penalised players through fines and bans for the most innocuous things such as running on the pitch, swearing at one’s own poor play or fortune, expressing disappointment at an umpire’s decision and shaking one’s head on being given out.

In the year since the new rules were introduced, a shocking 47 players have been reprimanded, with more than a few bans having been handed out. And hence, players’ livelihood has become dependent on their ability to conceal their emotions on the field, to be disciplined and orderly. Administrators make rules to choke out any violence in bouncers and verbal abuse (aka sledging), mistakenly thinking that this is preserving the ideals of Test cricket, while remaining woefully ignorant to the realities of players and their fans.

***

Let us take the hypothesis that Test cricket, despite being a gentleman’s game, was intended to be a tough game, physically and mentally. In that case, what is the evidence that Test cricket pushes you to the limits of your mind and body’s capabilities?

Let’s examine a single ball. A bowler needs to run in at close to full speed, leap up into the air, get his feet into position, and land with a force close to seven times his bodyweight, all the while rotating his arm, without bending the elbow, as fast as he can. He then needs to hurl a projectile at close to a hundred miles an hour, making it deviate in the air and off the pitch. If he misses his mark by more than a few inches, he’s failed. After this incredible effort, he needs to abruptly change direction, and catch the ball if it comes back to him. He would need to repeat this incredible feat of strength and skill about 300 times over the course of the game.

As for the batsman, he must anticipate where the ball may land, react to it, get into position, swing his bat correctly to make contact with this 100-mile-an-hour thunderbolt, before then coordinating with his teammate on whether they can both sprint 20 meters in full equipment before the ball breaks the stump. And that’s just one ball. The great Test batsmen bank on being able to complete this test of skill, strength and timing for hours on end. It’s hard to think of any other sport that challenges its players’ fine motor skills, mental endurance and stamina the way Test cricket does. But still, Test cricket has a somewhat ‘soft’ reputation.

But danger is necessary in a sport after all (Well, at least the Greek philosopher Plato thought so). And Test cricket is a dangerous game. Bouncers and close-in fielding put players at risk of ‘acute’ injuries, while the rigours of the game lead to chronic ones – Dean Jones nearly died from exhaustion after his infamous Chennai double ton.

And there is something exciting about the violence and brutality of danger. Extreme sports wouldn’t be a billion dollar industry if it weren’t. Yet, cricket administrators have failed time and time again to capitalize on this idea, and continue to stumble incoherently in the same boring alleyways.

Teams are prohibited from intimidating their opponents; bowling more than two bouncers in an over is not allowed (in Tests). One may point to the tragedy that was Phil Hughes’ death as a reminder of the potential consequences of bouncers, but one must remember that his death was a freak accident, and that protective equipment must adapt to meet the rules of the game, rather than the other way around.

Field settings prevent “negative” bowling and “leg theory” by prohibiting more than two fielders behind square on the leg side, another measure made in part to prevent aggressive fast bowling. And as a result, you only get whiffs of aggression.

There is nothing quite like a huge fast bowler bowling at breakneck speed. Wahab Riaz, Mitchell Johnson, Mitchell Starc, Shoaib Akhtar, Shaun Tait: they all had their primary weapon - fear - hampered by legislation. And as a result, the viewing public rarely got to see the displays of aggression they are after.

Forget the gentleman’s game for a moment and cast your mind back to Wahab Riaz’s spell to Shane Watson, or Mitchell Johnson in the 2013-2014 Ashes. That was Test match bowling. Those contests, where the audience can see the fear in a batsman’s eyes, that is cricket. Restricting bouncers and leg side fields, while being safety precautions, are administrators clinging on to an ideal of chivalry that cricket never truly embodied outside England (and they were the ones who invented Bodyline).

***

Cricket is on this path to self-destruction, where every time a player does as much as express his emotions, he is struck down by the ICC. During the Lord’s Test match earlier this summer, Kagiso Rabada bowled a rip-snorting bouncer to Ben Stokes, who was caught behind. Rabada, obviously excited, ran off screaming, telling Stokes to “f**k off”. Hell, every South African fan wanted to tell Stokes to f**k off. It was beautiful, adrenaline-pumping cricket p**n. Yet, Rabada missed out on the next game, shushed by the ICC for swearing.

Jason Holder swore in frustration when a match-changing catch was shelled in the slips. Holder has been captaining a hapless West Indian team for a few years now. And now, when they were finally beating a quality side in their own conditions, their slip fielders were throwing it away. His frustration was natural – it’s the highs and lows we fans watching a five-day long game for.

But within hours, he was struck down by the ICC, and a demerit point was added to his record. Tamim Iqbal’s team are routinely insulted by top sides. Australia didn’t bother touring for 11 years, and when they did, their captain reminded Bangladesh that they had won just nine games of Test cricket. And now, his team were finally beating the infamous Australians, and his twin 70s were the cornerstone of that victory. Damn right he was pumped. And surprise surprise, he was slapped with a demerit point.

The Ashes are the sensation that they are not because of the contests, which are often one sided, but the rivalry and animosity between the two teams. When Michael Clarke told James Anderson to get ready for “a broken f*ken’ arm”, viewers everywhere were riled up and ready to go – it made a boring match interesting, despite the moral argument. The India-Australia series of 2017 was awesome. Both sides played great cricket, but the heated contest between Virat Kohli and Steve Smith is what made it such a compelling series to watch.

But now, players are under the constant threat of bans and fines and demerit points make sponsors wary of endorsing those players. Test cricket is a tough game, mentally, and that’s one of the main reasons that it’s lasted so long – the public likes a fight. Watching two teams go at each other with everything they have is what audiences crave.

Let’s leave our premonitions about Test cricket aside for a minute and think about what looser laws on sledging and intimidation bring. More aggressive, more potent fast bowlers. A contest with the edge and barbs to bring audiences out in the thousands. Test cricket is not dying, but it is being slowly killed off by a stupid ideal – that of a gentlemanly game. The first great cricketer, WG Grace, was no gentleman. Yet he was the biggest celebrity in Victorian England.

Sport’s great contribution to society is to teach good values. Scyld Berry, in his book, Cricket – The Game of Life, argues that in cricket, it is done through the story of the batsman, who has to display strength, speed, skill and stamina to persevere. He needs to develop mental toughness and immense courage to be successful, and in return, the audience idolises him.

Sport functions in society to praise good deeds of some athletes and blame others for their bad ones. This dichotomy is best shown in cricket, where the batsman represents all that is good in the world, while the howling, screaming, angry fielding side are his adversaries. But we’ve reached a point where the governing bodies have taken away the villains’ evil moustaches and scary guns. And there is little chance of creating a ‘hero’ in the batsman, when the villains sit limp and ineffective in the corner, too scared of demerit points to give the heroes any real obstacles.

***

There’s nothing in this world like a fight. As children, we enjoy the ungainly kerfuffles of the school playgrounds, where I’m told legendary wars are fought over pencils, crayons and childhood crushes. As angsty teenagers, we pretend to have gotten into fights of great violence and injury – for whatever reason. And finally, as adults, we crowd around the drunken brawls at bars and clubs and traffic jams, all the while giggling furiously as the blood surges through us.

WWE, essentially large men pretending to hit each other, is immensely popular around the world. UFC is capturing audiences like never before and Floyd Mayweather earns millions of dollars for beating people to a pulp. It’s primal, it’s brutish, it’s what we want. It is every man, woman and child’s fantasy at some point to take out a terrorist or robber singlehandedly. It’s on all of our TVs, in our minds and in our blood – but very rarely in our cricket.

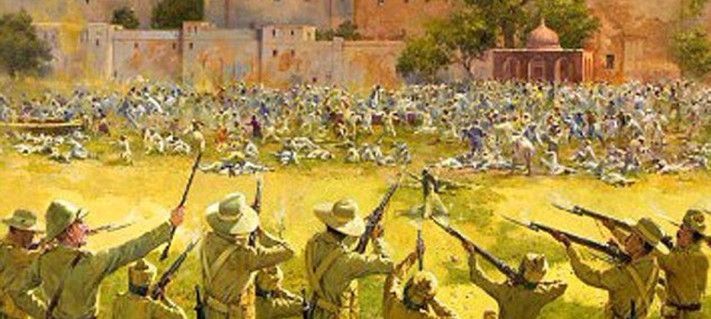

The West Indian teams that dominated world cricket in the 70s and 80s were fighting against much more than just their opponents – they were fighting against racial oppression, they were soldiers for equal rights, champions of their people in many ways. And their cricket reflected it. Sir Viv played fearless, helmetless cricket – every shot he played and every piece of gum he chewed was a ‘screw you’ to the oppressors of generations past.

Their bowlers were menacing, intimidatory, predatory even. With every bouncer, they reclaimed a region’s pride. Caribbean cricket reflected its people’s struggle for freedom – a tidal wave of anger and resentment built from years and years of being treated like second class citizens. That fight, that incredible need to win to empower a people, is no more. Yet, series after series are named after famous freedom fighters and moments in history. Freedom Trophy, Independence Trophy, Friendship Trophy – again and again, cricket draws on countries’ nationalistic pride.

Freedom didn’t come easy. There was blood, sweat, tears and more blood. There were no gentlemen. Yet, cricket is determined to whitewash over that pain and suffering, all the while calling upon our patriotism. It is only when Test cricket becomes one with its people and adequately reflects the individuality of each of its member nations will it become popular again.