Not watched, but not unsung

A win is quite all right but give us a hard-fought draw any day.

For many contemporary cricket fans, fed as they are on an overdose of limited overs cricket, that might seem like a romantic but vacuous sentiment. One presumes, however, that it would resonate with those few who still follow Test cricket, particularly if they so do because of their love for its protracted swells and ebbs.

They would tell you that cricket’s soul resides as much in a match-saving two-hour 18 not-out on a crumbling Wankhede wicket or a traditional WACA trampoline, as in a match-winning two-hour 125 on the featherbeds of the Oval or the Premadasa. One might look at them askance, until one realises that there is something rather relatable in a couple of batsmen trying to hold on to dear life because, as Kipling would have it, their “Will…says to them: ‘Hold On!’”

The list of batsmen who have held on over the years reads like a litany of the game’s great and good. If Faf du Plessis, Gautam Gambhir, Ricky Ponting, Andy Flower, Michael Atherton, Jack Russell, George Headley and Hanif Mohammad were to dust off their forward and backward defensives and to take guard in the last innings of a timeless Test match, there is no telling when (and if) the match would finish.

The averages of these batsmen might span the statistical ground between the mediocre and the excellent – what with one of them averaging in the late twenties, one in the early sixties and seven in between – but they are united in having played one match-saving opus each (in Mohammad’s case, two) during their careers.

The legend of innings unseen

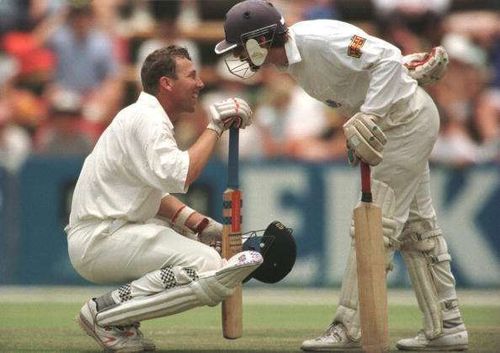

Still, some match-saving innings are more quickly remembered, more fondly recalled, than others. To this writer, the term ‘match-saving rearguards’ immediately brings to mind Hanif Mohammad’s monumental 337 versus the West Indies at Barbados in 1958 and Atherton’s marathon 185 (assisted by Jack Russell’s gravity-defying 29) versus South Africa at Johannesburg in 1995.

I was probably living a previous life when the former innings was played and did not, having no cable television at home in 1995, catch the latter live. Nor, till recently, did YouTube videos of either innings become available. What I heard about these innings, however, more than made up for what I had missed visually, as they came to occupy a hallowed space in my mental library of cricketing things.

Of course, in no way does the legend of those two unseen innings take the gloss off Gambhir’s meditative 137 at Napier, Ponting’s stubborn 156 at Manchester, Andy Flower’s resourceful 232* at Nagpur, or Du Plessis’ undefeated 110 on debut at Adelaide: no doubt, these were superb innings, considering the contexts and the bowling attacks in and against which they were played. In being televised and repeated in highlights packages, however, they seem to have lost something of their essential substance, ridding them of the sort of exotic aura which colours match-saving innings that were played when cricket was not on television or, if it was, not too much.

Less, therefore, seems to be more at least as far as the telecast of backs-to-the-wall match-saving Test innings is concerned. For, the less such innings are watched, the more scope there is for the imagination to probe into the circumstances and the skills that occasioned them. The probe itself invests the innings with a certain emotional appeal that reason finds it difficult to suppress or surpass. There is little surprise then that they do not remain unsung even if, and especially because, they have not been watched.