Rebel Richard Austin: No redemption in sight

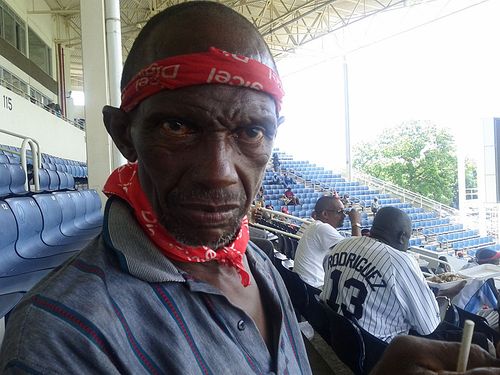

Richard Austin – once a cricketer, now a wreck

“How did it come to this? “

Thus spoke Théoden, king of Rohan, in J.R.R.Tolkien’s legendarium The Lord of the Rings.

And with good reason too – because for some of the survivors of the ill-fated rebel West Indies squad that toured apartheid-era South Africa in the summer of 1983, the question simply breaks down their defences, causing all the bottled-up emotions to gush forth like raging torrents.

There is no redemption for them, no last hurrah, no gaggle of adoring fans even among the old-timers flanking them as they move from one place to another. Only one of that party found eternal peace – in a different world.

All because of one moment of defiance for one simple reason - a steady income. For in those days, cricket rarely saw the obscene amount of moolah that is liberally pumped into the game and of course, into the coffers of today’s stars.

Three of that 18-member side are now pale shadows of their former selves. David Murray, son of the legendary Sir Everton Weekes, and one of the finest wicket-keepers ever, has struggled with drug issues, and is now reduced to peddling them just to survive. Herbert Chang, a notable exponent of the willow, wanders the streets of Jamaica’s towns in a perpetual trance, and is rumoured to be dying.

And then there is Richard Austin, Kingston’s most talented all-round cricketer who played only two Test matches and a single ODI for the national squad.

Looking at him now – head tonsured, eyes bloodshot and rheumy, disheveled and high on cocaine – one would be forgiven for assuming that he is one of the deadbeats that infest the violent ghetto area of Jonestown. There is no sign of the once-invincible sportsman (he represented Jamaica in football, and was a talented table-tennis player by some accounts) who once pulled off a sensational catch to remove the legendary Graham Yallop of Australia in a game at the Kensington Oval.

It isn’t every day that you get to meet a player who could bowl at good pace and spin the ball just as well. It also isn’t a coincidence that he happened to form an extraordinary combination with Franklyn Stephenson – the greatest cricketer to have never played for the national team – at the height of his powers.

And it is decidedly unfair on the man because he, unfortunately, happened to arrive at a time when the Calypso kings dominated world cricket ruthlessly. A side that boasted of players such as Viv Richards, Clive Lloyd, and the fearsome pace battery which ravaged other international teams was difficult to break into; such was the mastery they exerted on the game.

Austin signed up for Kerry Packer’s circus – World Series Cricket – after the first two Test matches against Australia in the 1977-78 season. The West Indies cricket board, incensed, dropped him for the third Test along with wicket-keeper Deryck Murray and opener Desmond Haynes; Lloyd and the rest of the WSC contractees in the side staged a walk-out, forcing the board to play a side that could, in the most polite of terms, only be described as a second-string team.

The good thing was that Austin’s form remained unaffected, and he went on to top the domestic season’s batting averages.

Then came the beginning of the long, dark tunnel; only this time, it seemed interminable.

He was only ever on the fringes during his time at WSC, and once Packer reached a settlement with the Australian cricket authorities, was cruelly ignored by his own nation’s board.

He was struggling to rake in the cash, but more importantly, he was missing out on international exposure, unable to savour that intoxicating feeling of pitting himself against the world’s best at the time. Desperation was starting to seep in now, and the feeling of disenchantment was beginning to reach alarming proportions.

So when Austin was made an offer to sign up for the rebel tour of South Africa in 1982-83, he accepted it promptly.