Sachin Tendulkar - Of 22 yards and 24 years.

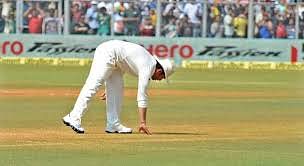

Paying his final homage

I am 19, and like more than half of India’s current population, I wasn’t even born to read about his record breaking heroics as a child prodigy. I wasn’t born then, while he rose up the ranks and announced himself on the international arena. I wasn’t born to be able to see him continue batting against the doctor’s advice, while blood gushed out of his chin, trickling over on to the pitch. He was 16 at that time, and was hit by a bouncer on his first international tour.

Was he too young to be pushed on to the big stage? By his own admission, he wasn’t quite sure about his status. I still wasn’t born to be able to see him score Test centuries on 4 different continents even before his 20th birthday. Needless to say, he had conquered all his doubts by then and made the stage his very own.

Meanwhile, I was born; but still, I was too young to recollect where I was when the ‘desert storm’ arrived. Too young to remember where I was sleeping, while the best bowlers were having nightmares about him. Too young to comprehend why captaincy was not his cup of tea. Too young to analyse how the batting order collapsed after his wicket fell.

I was gaining sense, while he gained the support of a few trustworthy young men and a fearless captain to share his responsibilities. My memory is vivid now. I remember him lighting up the ‘dark continent’, but joy eluded. And by the way, though I was gaining some sense, it took me a long time to realize that MRF actually manufactured tyres and not bats! That heavy wood was taking its toll now. He was in pain and agonized by an uncertain future.

However, I do remember his grand resurgence. A resurgence which culminated in him experiencing his ‘ultimate moment’. He got his ultimate moment, but when shall I get that one chance to see him bat live in front of my eyes? Well, I got the chance; not once, but twice. On both occasions, it didn’t matter how many he scored. What mattered was to be a part of the festival which would inaugurate at the fall of the second wicket and continue as long as he was on the pitch. It felt like a virtual conversation between him and the crowd – a connection which satellite TV fails to portray.

You have to be at the ground, on your feet to experience that. Not much is said during that conversation though. As he walks in crossing the boundary rope and towards the batting crease, he quietly acknowledges our love and support and asks us to be quiet. But we refuse. He generously accepts our refusal, taking guard and preparing to face the ball, while we continue the hysteria. The conversation doesn’t end with the first ball; it continues as long as he is in the middle and until he is dismissed. While he walks back, we are again on our feet, thanking him; he says he will come back.

But not this time. Yesterday, while watching him take the final lap of honour, I was quietly recollecting these with a heavy heart and telling myself, “it is over now”. But suddenly, I held my breath once more as he walked towards the pitch for the last time. He had saved his best for the last. I was stunned as he bent forward, first the right hand, then the left one. He touched the pitch and got up, preparing to leave. We could see him wiping his moist eyes while he left. I am sure a tear drop quietly tripped over on to the pitch while he was bending over. That one tear drop would go on to live harmoniously with those few drops of blood and countless drops of sweat which had already been shed in the course of 24 years.

This final act was a merger of the 22 yards with the 24 years.