Sachin Tendulkar: The brand that God bottled only once

A gentle disclaimer before you read any further into this article is that it is not about statistical one-upmanship, my hero was better than yours piece. On-board? Okay, great.

While speaking to a close friend’s dad recently, he recapped the toughness of the challenge that Sunil Gavaskar faced while going up against the might of the Caribbean pace quartet. He was reminiscing, with rose-coloured glasses of helmet-less gladiators. Then he showed me the hand-written correspondence from Gavaskar to him dated January 1984, as one of his most prized, and proud possessions. He symbolized something for that generation, did Gavaskar, beyond the records and scorecards. Similarly, my friend and our contemporaries talk about what Sachin Tendulkar meant and stood for, for our generation. Things change, situations alter, circumstances vary, game evolves. The fact that Virat Kohli’s brilliance has still not resonated deeply with enough Indians as much as MS Dhoni’s story or Tendulkar’s illustrated journey has been pointed to cricket stopping from being a vehicle towards something larger for Indians in this insightful piece by Santosh Desai. He argues, that cricket is now just a game, and India doesn't need to prove itself to the world through cricket. In an era where the boundaries come in, and there is not more than a smidgen of reverse swing, the sixes probably lose their wow factor. Maybe it is just reducing the special to the quotidian and mundane.

The larger point however, is that every era has had a champion Indian batsman to root for. It is foolish to compare one to the other when every single variable that defines their performances have changed. India, in fact, is a very lucky nation to have had 3 absolute world-class batsmen, following one after the other. Tendulkar burst on to the scene in 1989, just a week after the Berlin Wall fell, just a couple of years after Gavaskar, who had been there since 1971, hung up his boots; and Kohli took the mantle when his idol was raging against the fading light in the twilight of his 24-year old career. So since ‘71, now close to 48 years, India had a player to expect outrageous things from.

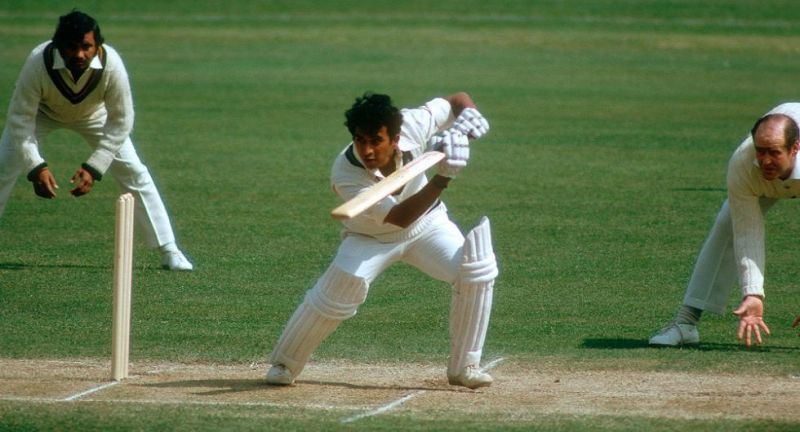

In Tests, there was always Gavaskar to snatch a draw from the paws of defeat, there was always Tendulkar, despite gob-smacking artistry somehow conspiring to snatch defeat from winning situations, and now there is the current skipper snatching win after win, with the ruthlessness of Alexander the Great. While Sunny’s drives stuck to the carpet and the textbook, Sachin’s shots were dynamite wrapped in silk, Virat’s strokes are sinewy nonchalance. Each has contributed to the rise of the next. Without Sunil Gavaskar, there is no Sachin Tendulkar and without whom, a Virat Kohli would not have been possible. Each has built on the edifice that the previous maestro left behind. The little master had one format, the guy from Bandra had two and now the Delhi lad has three.

As habitual followers of cricket in the 70s and 80s will ask while keeping a check of the match situation on the transistor – Score? Gavaskar hai na? (What’s the score? Gavaskar is unbeaten no?) which gave way to the 90s and 00s iteration - Score? Sachin?

And with the answer, they’d know if there was any hope for India. It is perhaps the hope factor that feeds the notion that Sachin is an emotion. Subliminally, there was a personal attachment to him, even for those who loved to hate on him, accusing him of being selfish. They use that lash even today. But the fans felt his failures cut deeply, we feared for his wicket knowing fully well the domino inducing consequences. He was the kid that every grandmother prayed for, every youngster looked up to, every household rooted for, every city cheered for, every nation longed for.

But India had him.

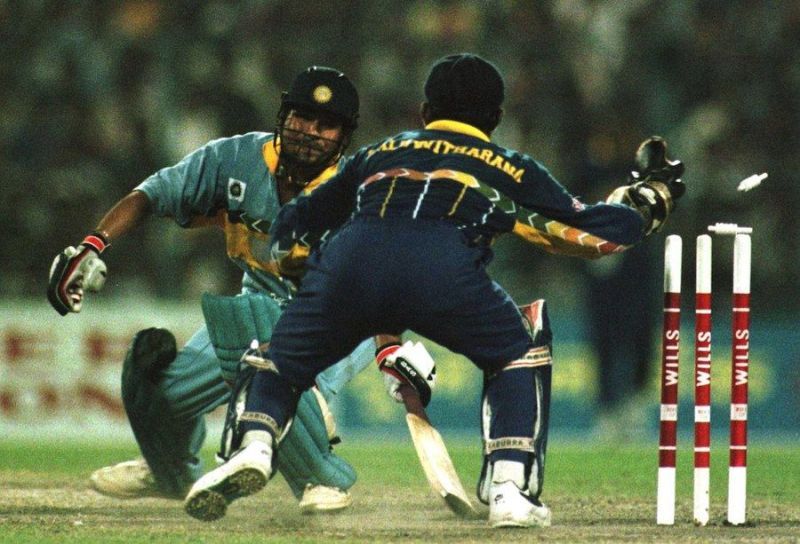

Newly liberalised Indians couldn’t quite believe that we had the good fortune of claiming credit for. His runs belonged to us, even when they didn’t fetch victories. It might seem perplexing now, that people were happy for the runs despite of them coming in a losing cause. In scores of matches, plotting his fall was all the opposition had to worry about. Which was an awful lot, but still, you get the gist. When Sri Lanka was in the ascendency in the late 90s, their skipper Arjuna Ranatunga knew what to do in matches against India. He’s on record saying,

"you get him out and half the battle is won."

His runs made sure India slept peacefully, with a smile of content, with a promise of better things to come. An innings of his could be a balm for the fraying nerves, a booster shot of adrenaline, a blueprint to copy, a window to the new. We basked in his reflected glory. He was a mould breaker offered in the most unconventional of packages. We now kind of forget his heavy bat, squeaky voice, dorky shyness, John McEnroe hair, ripping leg-breaks, wobbly seam-ups, unexplainable courage, and a rocket-arm for a pint-sized man-child.

His technique was one the most balanced and his defence one of the most impenetrable, as is the case with most Bombay-bred batsmen primed for Test cricket. But what made him a few notches above the rest, something ratified by the Sir Vivian Richards and Sir Don Bradman is that he invented strokes –

The paddle sweep, the lofted straight drive, the full-faced edges, the cramped but lofted extra-cover hits, and the various upper-cut over slips. Even his wristy flick and its follow-through seemed differently, more beautifully executed than others. And only he could play a rash flat batted cover-drive against Shane Warne and still make it look like it was from the Wisden cricketing manual. His strokes inspired awe because they were ahead of their times and not a product of it. Not only did they fetch runs, but they displayed to a whole generation of aspiring cricketers the possibilities with a willow they couldn’t have imagined. He even produced a clone from Old Delhi who opened, quite successfully and with devastating effect with him. For years, for at least 3 different generations, there he was, putting up a show, divorcing himself from the crushing expectations of millions, playing a care-free brand of sublime batsmanship. Imagine the mental fortitude needed for that.

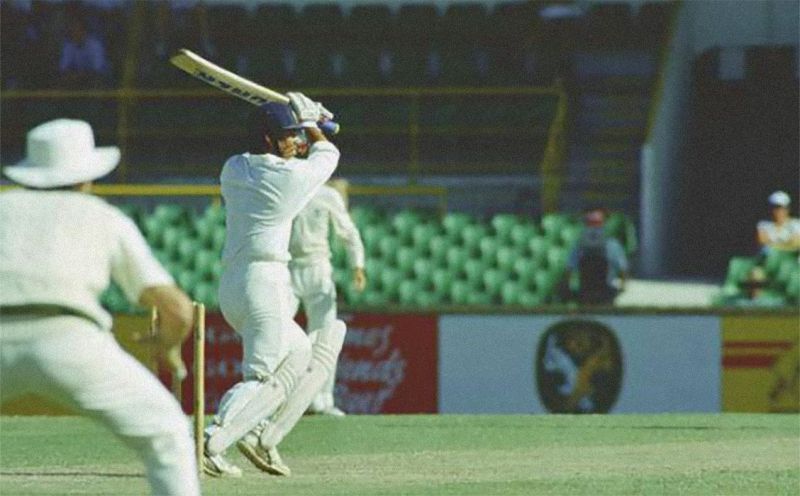

To illustrate with a forgotten example, because repeated acts of genius run the risk of not giving the same thrill; exactly 9 years to this day in Newlands, Cape Town, he made his last Test hundred. Walking in at 28/2, Dale Steyn and Morné Morkel tearing down from each end with Lonwabo Tsotsobe in the support act.

The wicket had bounce, the cherry was seaming troublingly and swinging menacingly. The wind was both encouraging the bowlers and cooling off their perspiration, egging them on for longer, meaner spells. There was nowhere to hide for respite in face of relentless fast-bowling. The series was on the line. A collapse meant another defeat in South Africa, who had 362 on the board. More than enough. Dale Steyn's magical wrists were ripping one vicious outswinger after the other, as if he had the ball on a curved string. Steyn (5/75) was operating at such a high level that the bar was raised and Tendulkar relished the challenge. The hard to please Ian Chappell was effusing praise

"The ball moving around off the seam and Dale Steyn was at his best, and Tendulkar showed his class, his true class, in scoring 146. This was another side of him, just showing his greatness - his ability to make runs when things were really tough and he really had to battle."

Steyn at his peak required Tendulkar at best to be nullified. He played everything in line, close to the body, under the head, ever so late with softest of hands and clearest of intentions. Every stroke was controlled, every leave deliberate, except the top-edged six that brought up his last Test century. He hit 17 fours, 2 sixes as he shepherded India to a 2-run lead. He was 37. At this point, doing this for 20 years and counting. His final gem in Cape Town, as shiny and thrilling as his first in Manchester.

Maybe, to counter this 146, old-timers will point to Gavaskar’s 96 against Pakistan in the fourth innings on a snake pit of a surface in Bangalore in his final Test match. Indeed they have a fair case. And that’s why if I have to choose someone to open in a Test and write bestselling books (Sunny Days, 1976; Idols 1983; Runs 'n' Ruins, 1984; and One Day Wonders, 1986) I will choose Gavaskar; to chase down any target with cruel, calculative precision while being insouciant to opinions, I will choose Kohli; but to bat for your life, bringing contagious joy, oohs of exclamations, and mass adoration across counties and countries, I can’t look beyond the guy named after the legendary Sachin Dev Burman.

It’s purely for the joie de vivre he brought. Millions have experienced it, again and again and again. Yet it never got old - the happiness through Sachin.

God bottled that brand only once.