Sachin's Children - Memories of Master and India's Second Coming

We are the children of liberalization. No sir, not for us the Hindu Rate of Growth. Or the stolid pervasiveness of the Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices Act. Our shiny new economy would rather pander to the gods of competition. As we take our first tentative steps into what we, or rather our parents and teachers, rather unimaginatively termed the real world, we will, at the resto-pub after work, bring up Govinda and Main toh raste se jaa raha tha to laugh at ourselves, our times; we will gradually grow out of the tendency to draw parallels between our lives and those of the characters on Friends, and to those who came after us, we will talk about the time our parents would be charged for calls they would receive on unwieldy handsets as registered subscribers of Orange and BPL. We see ourselves as the Saleem Sinais of the nation’s second coming, birthed at a time when the sleeping giant finally arose. When our histories are written, you will see that we were the first ones to guzzle Pepsi, chomp on Maharaja Macs and prefer limited overs cricket. Nostalgia is not a prerogative of the old. It can be claimed by anyone who has lived for more than a day. Oh, you remember the time when I was alive, say the dead. Oh, you remember the time when I was alive, say the living.

As we now stand on the cusp of the greatest challenges of our lives, we think about the man we grew up with, who grew up with us. By announcing that he will not put on a coloured jersey to play cricket for our country ever again, our beacon, to whom we were inextricably tied at the moment of our simultaneous ‘births’, has deserted us, for we have not known a world without Sachin Tendulkar.

Certainly, our parents will cope. Adulthood brings with it some sort of locking of vision. When we are young, we can tinker around, choosing to focus and un-focus at will, shifting the angle or position of the camera if we wish to see a different image through the lens. You know you have arrived into adulthood, or the end of growing up, when you feel forced to finally capture the shot, when you finally feel burdened by the tyranny of the unflinching truth represented by the single dimension.

Certainly, our parents will cope. Adulthood brings with it some sort of locking of vision. When we are young, we can tinker around, choosing to focus and un-focus at will, shifting the angle or position of the camera if we wish to see a different image through the lens. You know you have arrived into adulthood, or the end of growing up, when you feel forced to finally capture the shot, when you finally feel burdened by the tyranny of the unflinching truth represented by the single dimension.

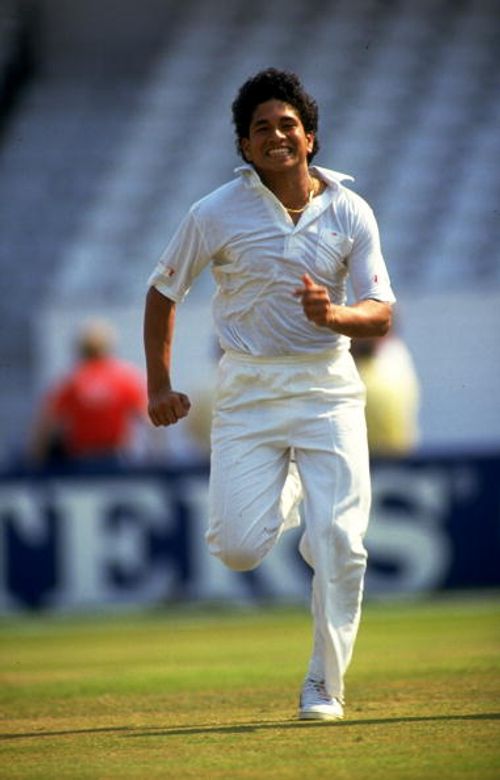

So when a curly-haired young man began playing stokes of unmatched quality in the early nineties, they were saying to each other, “He’s not really better than Sunny. You see, their styles are completely different. Sunny was a classic Test-batsman.” We gulped down our Boost, and merely said “Wow. We want to play cricket for India like Sachin Tendulkar.” 1996 was our first real World Cup. That is why we think Viv Richards never really played one-day cricket. He didn’t wear coloured pyjamas and his bat never said Wills. Sanath and Kalu ensured that we would find it absurd when an opening batsman was anything but a swash-buckling cavalier, bludgeoning fast bowlers to all parts of the park. Meanwhile, our parents were twitching uncomfortably in this garish, post-Sunny era, when matches ended way past their bedtime. That is why they will probably not remember the inimitable Tony Greig memorably screaming “They’re dancing in the aisles here in Sharjah!” when Master single-handedly battled a sandstorm and Australia to put India into the finals of the tri-series.

Long before Ten Sports and Neo Cricket, we had only Star Sports and ESPN. Only our ilk will know the tingle of anticipation that rushed down our bony little spines every time those computer-generated, mechanical silhouettes of bowlers and batsmen would cross our television screens to announce the beginning of cricket programming on Star Sports. Our first lessons in cricket, and by logical conclusion, beauty, would be delivered in the assured analysis and pointed questioning of John Dykes, who would make us feel like privileged participants in a world where men did not have to mug up multiplication tables and where the only thing you were expected to have an opinion on was how Taylor would set his off-side field against Master.

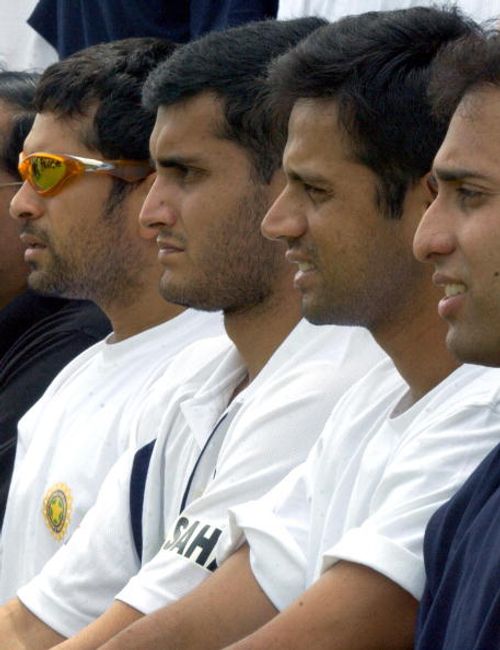

We did not prefer Test cricket, but that did not mean we did not watch it, especially when the situations it threw up assumed ODI-esque contours, like that time at the Chepauk in January 1999 when Master almost snatched victory from right under the noses of our other, admittedly lesser, heroes, Wasim and Waqar. By this time, of course, we had other gods within our team too. They went by the names of Dravid, Laxman and Ganguly. God knows they played their parts, and played it well. Their only competition was among themselves. Countless boys growing up in the nineties, as they gulped water in between the innings of their own matches on dusty playgrounds and concrete pitches in the compounds of co-operative housing societies, would, in line with their own cricketing and philosophical foundations, make a case for their hero. The aggressive vouched for Dada, the gritty workmen would bat for Dravid and Laxman would find allies in the artists. Master would rarely feature in our boyish banter, which in the folly (or wisdom) of our youth, would assume the significance of a political debate. In many ways it was, for we were young boys forming opinions and picking sides that we would continue to vouch for as young men, and not just from the admittedly instructive point of view of cricket. What do they know of cricket who only cricket know, CLR James famously wrote. We, the fellows who painstakingly constructed innings and the pinch-hitters who played every ball like it was a new day, agreed on only one thing – the greatness of Master.

We did not prefer Test cricket, but that did not mean we did not watch it, especially when the situations it threw up assumed ODI-esque contours, like that time at the Chepauk in January 1999 when Master almost snatched victory from right under the noses of our other, admittedly lesser, heroes, Wasim and Waqar. By this time, of course, we had other gods within our team too. They went by the names of Dravid, Laxman and Ganguly. God knows they played their parts, and played it well. Their only competition was among themselves. Countless boys growing up in the nineties, as they gulped water in between the innings of their own matches on dusty playgrounds and concrete pitches in the compounds of co-operative housing societies, would, in line with their own cricketing and philosophical foundations, make a case for their hero. The aggressive vouched for Dada, the gritty workmen would bat for Dravid and Laxman would find allies in the artists. Master would rarely feature in our boyish banter, which in the folly (or wisdom) of our youth, would assume the significance of a political debate. In many ways it was, for we were young boys forming opinions and picking sides that we would continue to vouch for as young men, and not just from the admittedly instructive point of view of cricket. What do they know of cricket who only cricket know, CLR James famously wrote. We, the fellows who painstakingly constructed innings and the pinch-hitters who played every ball like it was a new day, agreed on only one thing – the greatness of Master.

In that World Cup clash in 2003, when he played those three successive strokes against motormouth Shoaib Akhtar – the upper cut for six, the flick of the wrists to send the ball to the square leg boundary and the gentle push that ran away to the on-side fence – we saw how a legend could convert another man’s greatest weapon into his most telling weakness. On that afternoon at the Centurion, Sachin Tendulkar turned Shoib Akhtar’s pace into his greatest liability, using his unique combination of skill, temperament and – here lies the difference – genius. Most of us would have been in college when he became the first cricketer to rack up 200 runs in an ODI – and there was a heavy exchange of text messages and phone calls on phones that were smart.

Those of us who grew up in his own bastion of Bombay, accept that he is the entire nation’s jewel. But they can’t resist the temptation to point out to a visitor the vast expanse of brown behind a canopy of trees on the way from the suburbs to South Bombay and say, not without a hint of pride – This is where he started playing cricket; this is Shivaji Park.

Once, when travelling in an autorickshaw in Sachin’s childhood neighbourhood of Bandra East, a visitor would deign to ask the elderly driver, “Uska ghar kahaan hai pata hai aapko?” and without looking back, while keeping his eyes fixed on the road ahead, the driver would memorably say, “Unka bolo, uska nahi”. The ever-so-watchful Sachin would have surely seen our own decline. In those days, we would stand outside showrooms in Khar to watch him bat, alongside shopkeepers, small time traders, office executives in between meetings and daily labourers, all of us dispersing wordlessly when he’d get out. In the last of our college days and the first of our working ones, we sat around with quarts of cheap rum on hostel terraces and cramped apartments, making an inebriated case for Master being conferred the Bharat Ratna, in the midst of all the laments of our botched sporting and personal lives, in that order.

Maybe it is not the time for eulogies yet. Surely, this is not a time for laments. When the eventual, final, irrevocable Test retirement does come along, there will be enough of all that. Reams will be written, praises will be sung, victories will be feted and the void that he leaves will be bemoaned. But, like we have pointed out before, we are the fast-food generation and we have grown up following our hero, our brother-from-birth, in his coloured pyjamas. This then, is not a premature obituary, because on this day, we feel like a grown up. The shot has to be captured now, for with Sachin Tendulkar’s retirement from the limited overs format of this great game, a way of life has been laid to rest.