The selection conundrum: Talent or performance?

‘When Sachin Tendulkar was born, did the nurses hand him over to his mother and say, there you go Mrs. Tendulkar, here’s a hundred international centuries?’ Cricket pundit Harsha Bhogle quipped during one of his most fascinating motivational lectures, addressing students at IIM Ahmedabad a few years ago.

Bhogle’s observation has deeper implications than what meets the eye. For a cricketing nation like India that has produced the likes of the spin trio of Bedi-Prasanna-Chandrasekar, the defiant Sunil Gavaskar, the legendary Kapil Dev and the god-like Sachin Tendulkar, it’s very easy to get swayed by individual performances that remind us of these greats in their glory days.

So it’s more often than not that we are reminded of Dravid’s dead bat when we see Cheteshwar Pujara defend, or Laxman’s elegance when we see Rohit Sharma flash his blade. Does he see the ball early? Does he have that extra bit of time to play the fast bowlers? How’s the release of the ball and seam position?

For better or for worse, talent in India is defined in this manner. And talent in India will continue to be defined in this manner, for years to come.

What Bhogle implies is the necessity to back that talent with the right attitude and justify it with the right results. Just like Tendulkar had to play as many as three to four matches a day – often ferrying from one end of the city to another – in order to fulfill the potential he was supposedly born with, all talent needs to be harvested. If not, this awe-inspiring facet of a player is rendered futile, his potential destroyed and careers laid to rest.

So what does one do? Choose a product that promises something big, or choose the one that helps the sales figures to back its efficacy? Do we go with the youngster who toyed with Dale Steyn in a single over in an IPL game, or go with the domestic run-machine who has scored tirelessly, year after year?

It all boils down to the national reality of talent versus the given record of performance. In some ways, it is fair to say that they are intersecting sets: talent and performance. .

When Ishant Sharma first broke on to the scene, he was this next big thing in Indian cricket. Tall and fast, he had made the Pakistani batsmen hop around on a dead Bangalore wicket and had made a mess out of the great Ricky Ponting in Australia. Yet, after seven years and nearly 60 Tests, he averages a below average 37.25 in Test matches and has just above a hundred wickets from 75 ODIs.

Contrast this with Javagal Srinath’s record, and it’s noticeable how the Karnataka pacer, despite not being as talented as Sharma, had a good additional 60-odd wickets at a similar juncture in his Test career. This supplements the fact that when Javagal Srinath was inducted into the Indian team in ’91, he was seen as the likely replacement for Kapil Dev and had earned a name for himself in the domestic circuit.

What we see here is an example of abundance of talent backed by mediocre performance in Sharma’s case, and performance oriented ability in the case of Srinath.

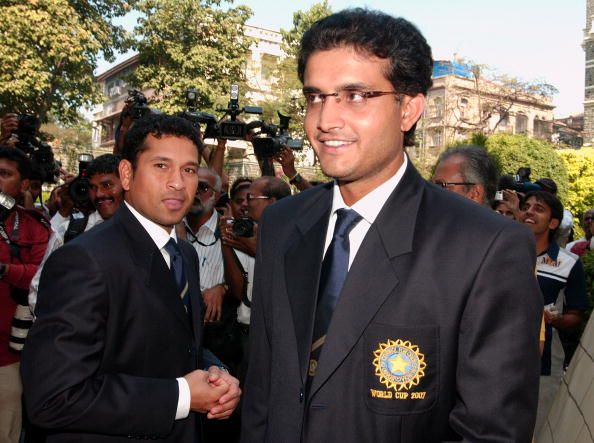

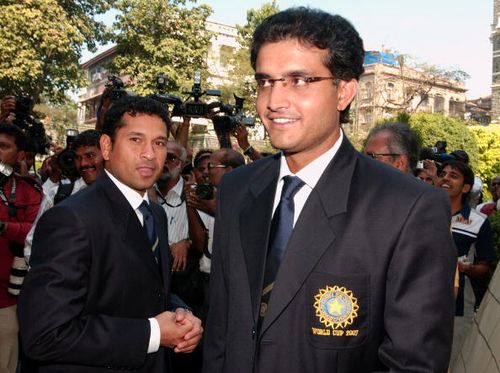

More often than not, people with great work ethics will succeed in doing justice to themselves and their backers. A flamboyant and temperamental Vinod Kambli had two double centuries in his first five Tests for India, and played only 12 Tests after that. At around the same time, often ostracized and pushed to the back seat, was a certain Sourav Ganguly who, even in the face of serious deficiencies in his game, went on to play 113 Tests for India with great aplomb.

Kambli’s discipline problems as opposed to Ganguly’s determination ensured that while Kambli would figure solely in the ‘talent’ set, Ganguly would be in the intersection that I mentioned earlier.

In the post-2000 era, we’ve seen Indian cricket’s obsession with talent grow, often at the expense of the careers of proven performers who could contribute handsomely. You often wonder what was needed from the likes of Laxmi Ratan Shukla and Rajat Bhatia to get into the Indian team, especially when they did everything right in domestic cricket, every year, for many seasons.

In the same period, Stuart Binny, a contemporary by age to both Shukla and Bhatia, ended up getting nine internationals for India (including three Tests), despite being at best a bits and pieces player. In 88 first-class games, Bhatia has scored 5,136 runs for Delhi, at an average of nearly 50. To back that up, he has 112 wickets at 28 a piece. The hero of Delhi’s 2007 Ranji triumph, Bhatia never got selected for the Challenger Trophy nor got a call up from the National Cricket Academy in Bangalore, let alone getting an India cap.

Sharing Bhatia’s fate, Shukla, a veteran of 129 first-class games, has 6,000-plus runs and 160 odd wickets to his name. Despite consistently being one of India’s better all-rounders, Shukla last donned the India colors when he was 18, and the year was 1999.

Binny on the other hand, doesn’t have a first-class or List-A record that could give statisticians a headache; he is as good as a Shukla or a Bhatia would be. But his claim to fame has been his IPL outings for Rajasthan Royals where, as a result of the odd sparkling performance, he was elevated to the national team and soon played a game for India at Lord’s.

When he was flying to Australia in January 2012, Manoj Tiwary, India’s most ill-fated batsman, had come off a stunning first-class season and an ODI hundred behind him. However, to give the “extremely talented” Rohit Sharma, more chances to settle into the Indian team, captain MS Dhoni benched Tiwary for as many as 15 games on the trot – perhaps the longest anyone has sat out after scoring a century in his last international.

This is symptomatic of Indian cricket’s talent-first policy. While there was no second thought about the merit of Rohit Sharma’s inclusion in the squad, on performance as the sole criteria, Tiwary deserved a final XI spot ahead of him.

Rohit Sharma went on to salvage the situation and performed satisfactorily in the long run, reposing the faith that the management showed in him. But that isn’t the case every time. When you fast-track the process of getting a player to play for India, you compromise on countless factors that groom him and make him the cricketer you want him to be, thereby running the risk of jeopardizing his career and growth.

Manpreet Gony had just one full Ranji season behind him when he was drafted into the India team for a tri-series in Bangladesh. This was done because of a single season of brilliance during the 2008 IPL, where he showcased talent that mesmerized all. In the subsequent Asia Cup, Gony made his debut against Hong Kong, went wicket-less, came back in the next game, took two wickets against Bangladesh, and was never considered thereafter.

Something similar happened with the raw Jaydev Unadkat, who impressed all while playing for Kolkata Knight Riders in IPL 2010, and during India’s A-tour to England. Unadkat, all but 18, was rushed into Test cricket against South Africa in Centurion, which exposed his frailties at the highest level and left him demoralized. He never came close to a Test call up after that match.

Performances or track records might not always churn out impactful displays, like we saw in the case of Pankaj Singh in England. However, they do stand as a metric to indicate a player’s abilities. It’s important to understand that while talent might soothe the eye and evoke jaw-dropping responses, the likelihood of it fizzing out is the greatest when it hasn’t been tested. We need to draw a line.

It’s always good to hear a youngster, yet to make his first-class debut, being drafted into the Indian team. But it’s sad to say that such moves hugely undermine the importance of meriting your place in the side, through something more than a ‘what a shot, this boy can time the ball well…’