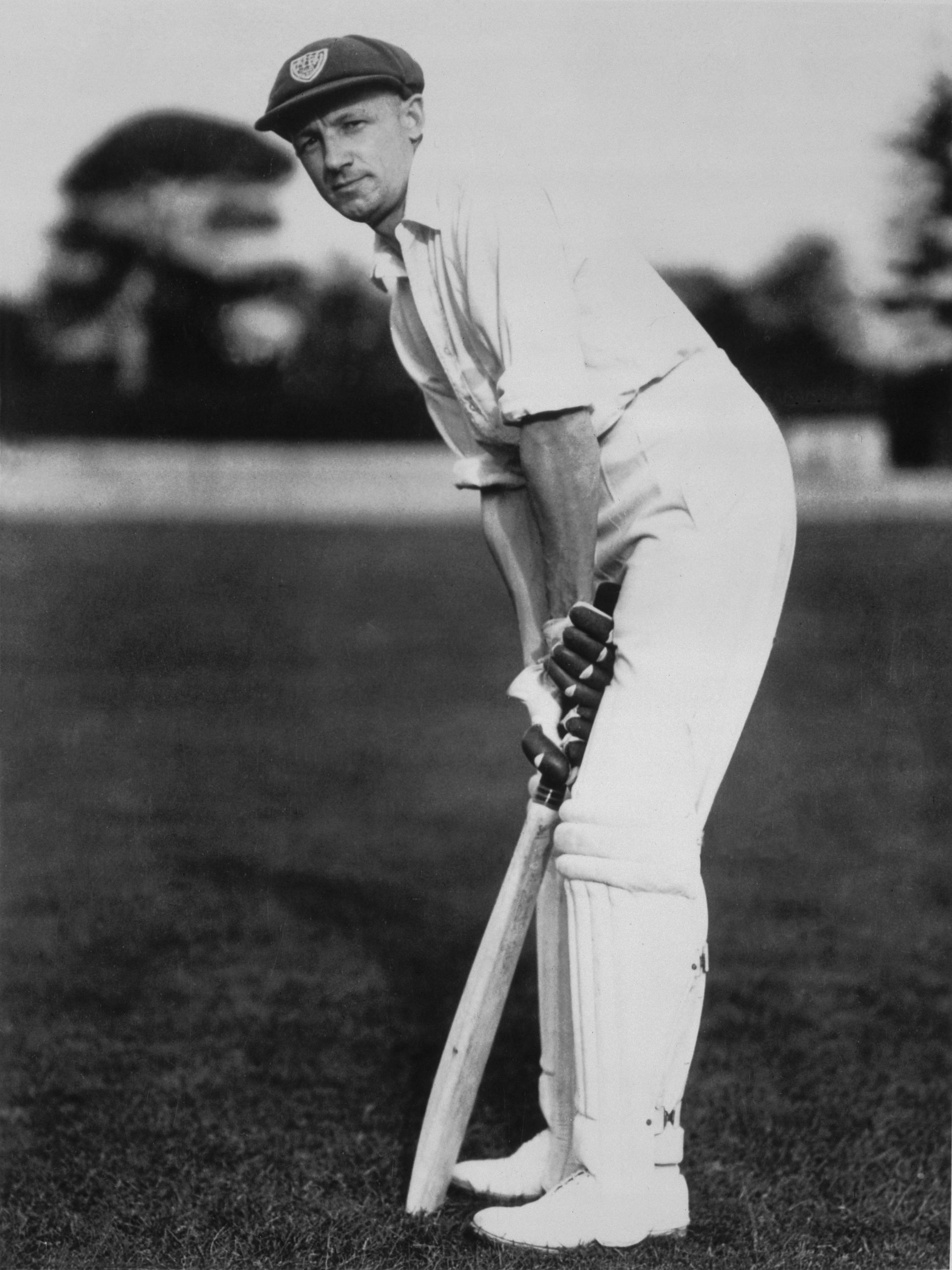

Sir Donald Bradman’s 1st Test series in 1928-29: Beginning of cricket’s most famous saga

Over the next 11 seasons that he represented Australia from 1928-29 to 1938-39, Sir Donald Bradman was the highest run-scorer every time except during the Bodyline season when he was second to Herbert Sutcliffe – the only two to aggregate 1000 runs – and in 1938-39 when he played just seven innings, amassing 919 runs at an average of 153.16, his best average for any season. He could not play in 1934-35 owing to illness.

Other than the two seasons during the Second World War, in 1940-41 and 1945-46, when Bradman did not play much – and in 1938-39 – he rattled up 1000 runs in each of the remaining 12 seasons Down Under from 1928-29 to 1947-48. There was no cricket for four seasons from 1941-42 to 1944-45. In 1947-48, he topped the run-scoring charts once again. Bradman was awesome during the four visits to England, heading the season’s averages and piling over 2000 first-class runs on each tour.

A prolific scorer coupled with consistency, Bradman was a phenomenon never seen before, nor ever after. E.W. Swanton put it in the simplest terms:

“He went on and on, over after over, hour after hour, hitting the ball with the middle of the bat. There was an inevitability about his play that brought the bowler to despair.”

When the 1928-29 season dawned, it brought disappointment for Bradman. He failed the Test trial for the Rest of Australia in Melbourne, managing scores of just 14 and five. Around that time, he shifted to Sydney, living in Concord West with the family of insurance inspector and associate of Percy Westbrook, G.H. Pearce, and working as a company secretary at Westbrook’s branch office.

He later took up residence, as per New South Wales regulations, with the secretary of the St. George Club, Frank Cash, and his wife, at Rockdale. The Westbrook branch office closed as the effects of the Great Depression began to be felt. Bradman was suddenly out of job, but luckily Mick Simmons Ltd., Sydney’s biggest sports store, recruited him to promote their cricket equipment.

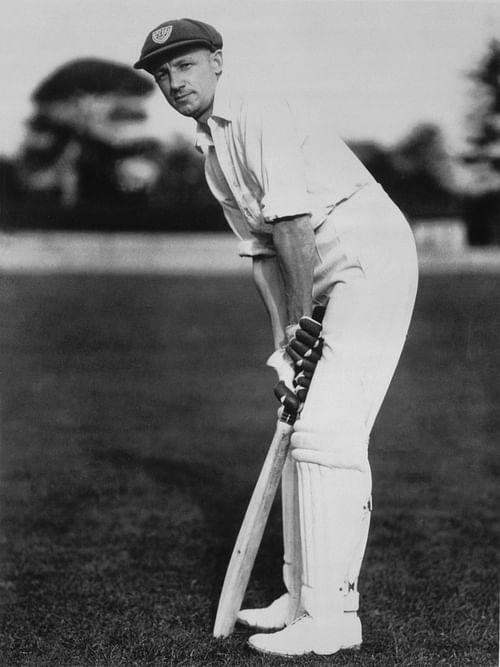

Back on the pitch, a young Bradman swiftly carried out a course correction, hitting three hundreds in the next four innings. One was against Percy Chapman’s MCC touring team. The promising 132-run knock earned him a spot in the Australian team for the first Ashes Test at the Exhibition Ground in Brisbane.

It was a disastrous Test debut for Sir Donald Bradman. England piled up 521, with Patsy Hendren hitting a fine 169. Bradman walked in at No. 7, with Australia in deep trouble at 71 for five. Maurice Tate trapped him lbw for 18. Harold Larwood snapped up six wickets for 32 runs as Australia folded up for just 122.

Bradman fared worse in the second innings, managing just one. Australia were humiliated, bowled out for 66 and beaten by a whopping 675 runs, the biggest margin in history. Very quickly had Bradman learnt what a tough life it was at the Test level. He was dropped from the playing XI for the second Test.

Having to carry the drinks as the 12th man at the exquisite Sydney Cricket Ground must have rankled the aspiring batter. Wally Hammond pulverized the Aussies with his 251 after Bill Ponsford had his left hand fractured by a nasty one from Larwood. Australia lost again, this time by eight wickets.

Recalled for the 3rd Test to replace the injured Ponsford, Bradman never looked back

The bitter experience, instead of demoralizing Bradman, only strengthened his resolve. He was determined to make his mark. He did it very quickly, and this was the only time that he was ever dropped from the team. Picked for the third Test to replace the injured Ponsford, Bradman never looked back thereafter.

After early damage caused by Larwood and Tate, Alan Kippax and skipper Jack Ryder put on 161 for the fourth wicket. Bradman consolidated the position with two useful stands with Ryder and Edward a’Beckett, scoring 79. But Hammond was awesome, bringing up his second successive Test double century, a round 200.

After wiping out a first-innings deficit of 20 runs, Australia again battled hard. Bradman joined Bill Woodfull with four wickets down for 143, and helped the ever-determined opener carry the score to 201. Woodfull scored 107, and then Bradman staged a wonderful rearguard action, adding 93 for the eighth wicket with Ronald Oxenham. Along the way, Bradman brought up his maiden Test hundred.

The crowd at the historic Melbourne Cricket Ground hailed the coming of a new hero, giving him a standing ovation. All of Australia was agog. As Ken Piesse wrote in The Cricketer International:

“Hats were thrown in the air, women waved their handkerchiefs and umbrellas. Motor cars hooted, tram bells clanged and passengers cheered and clapped.”

Bradman was eventually caught behind for 112. He was in for six minutes over four hours and faced 281 balls, striking seven fours. Cricket’s most famous saga had begun.

England needed 332 runs to win, and got them with three wickets to spare on the seventh day. Even today, there is a misconception in some quarters about timeless Tests. It is believed that there is only one instance of a timeless Test ever played - the final game between South Africa and England in Durban in 1938-39.

That, in fact, is the longest Test ever played, spread over 11 days, with nine days of actual play. It is well known that it was abandoned as a draw since the English team had to catch the ship leaving for home.

Up until the Second World War, Test matches in Australia were timeless, after which a six-day limit was imposed. In England, Test matches were initially of three-day duration, but from 1912 onwards there was a provision that should a series be undecided at the commencement of the final Test, then that Test would be played to a finish.

From 1930, Test matches in England were extended to four days, with the stipulation of a final deciding Test still being timeless in place. From 1948 onwards, the duration of Tests in England was extended, and limited, to five days.

There was a see-saw battle in Adelaide too, with Hammond scoring a hundred in each innings – 119 not out and 177. Bradman raised 82 for the fifth wicket with 19-year-old debutant opening batsman Archie Jackson before departing for 40, and this time Australia managed a lead of 35 runs. The highly-rated Jackson scored a memorable 164, coupled with his second innings knock of 36, totalling 200 on first appearance at the highest level.

The hosts were eventually set a 349-run target. Constantly losing his partners, Bradman was run out for the only time in his Test career, having made a resilient 58. It was 320 for eight, and his dismissal cost Australia dearly. They lost by 12 runs. Had Bradman stayed a while longer with Bert Oldfield, the result might have been different.

The battle of attrition also lasted a week. England’s left-arm spinner Jack White put in a Herculean performance, bowling 124.5 six-ball overs in the match, claiming five for 130 and eight for 126.

Since the First World War, the Australians preferred eight-ball overs. But during this 1928-29 home Ashes series, and the next in 1932-33, six-ball overs were bowled. Thereafter again, eight-ball overs were in force in Australia until 1979. South Africa, West Indies and New Zealand also tried this at various times. It was now 4-0, and as they say, there was little more than pride to play for in the final Test.

A 2nd hundred for Bradman in the final Test of the series

This Test, also in Melbourne, was a triumph for Bradman in more ways than one. Mercifully, Hammond’s run spree was over for the series, but Hobbs and Maurice Leyland got hundreds, and Hendren 95. The result was again a 500-plus total.

Woodfull ground out another hundred for Australia, and Bradman came in at No. 5, only to see the opener depart immediately. But Alan Fairfax gave him valuable support in a 183-run partnership. Bradman raised his second Test hundred, a fine 123, this time batting for 217 minutes, having played 247 deliveries and hit eight boundaries. Australia, though, finished with 28 runs in arrears.

Some fine bowling by paceman Tim Wall (five for 66), helped restrict England to 257. The target was 286 runs, but there were only a few minutes left in the sixth day’s play. So instead of the regular opening pair of Woodfull and Jackson, a duo of nightwatchmen in the form of wicketkeeper Oldfield and No. 11 Percival Hornibrook went in to face the top-class new-ball pair of Larwood and Tate.

The makeshift duo not only did a commendable job of guarding their wickets until stumps were drawn, but also laid a strong foundation by posting 51 runs on the board. Hammond was commissioned to break the stubborn stand, and he finally breached Hornibrook’s defense. The newly-hoisted top-order batter had eked out 18 priceless runs off 116 balls in a stay of 97 minutes.

Oldfield made a bigger point, holding on to score 48 in a stay of more than two-and-a-half hours. Then it was the turn of the real openers Woodfull and Jackson to get together in a stand of 49, after which Kippax and Ryder added 46.

Finally, Bradman appeared at 204 for five on the eighth day of the Test. Carefully, in harness with the captain, he carried Australia to victory. It took 134 overs and one delivery to eventually beat England. Bradman returned unbeaten with 37, just a tiny portent of things to come.

Wally Hammond piled up 905 runs at an average of 113.12. This was the highest aggregate in a Test series by a long way, surpassing the brilliant South African all-rounder Aubrey Faulkner’s tally of 732 in 1910-11, and Herbert Sutcliffe’s 734 in 1924-25, both against Australia.

For Bradman, it was a highly satisfying, if not exhilarating, initiation to Test cricket. He notched up 468 runs in his first four Tests, second in the team’s averages at 66.85 per innings. This was the only rubber that Australia lost, apart from the controversial Bodyline series of 1932-33, during the Bradman years. The 1938 face-off in England was drawn, while the other eight series ended on a victorious note.

How utterly mistaken ‘experts’ were in their assessment of Bradman

Not all Englishmen, though, were convinced by Bradman’s methods. Concluding that the hard, bouncy Australian tracks enabled Bradman to get away with the pull shot he so favored, Alfred ‘Tich’ Freeman told him, “You won’t be able to use those cross-batted shots of yours in England,” before he stepped on the boat and headed home.

As events were to prove later, the Kent leg-spinner had spoken a bit too soon. Surrey captain Percy Fender, who wrote a book on that 1928-29 tour, was also skeptical about Bradman’s technique, and there was a widely held view that this tendency to play across the line would cost him dear in England. Even the great medium-pacer Maurice Tate remarked:

“You’ll be found out when you come to England if you play like that.”

How utterly mistaken ‘experts’ can be in cricket was apparent even in the late 1920s. Bradman went on to register three of his best Test innings in England. Two triple centuries at Leeds and a 254 at Lord’s, which he himself rated as his finest. He averaged over 102 in Tests in England, and in all his four tours topped the all-comers first-class averages. Even in 1948, the English were still trying to figure out how to get rid of Bradman.

Decades later, and in retrospect, former England batsman Doug Insole summed up Bradman’s game and said:

“Don was completely different from Lara. He did not use many shots. He got into position so quickly that he could pull anything short and he made balls short that other men would have had to play defensively. He had a late cut and a hit through the off-side. But mostly his runs came from the pull.”

This is what Freeman had seen during Bradman’s maiden Test series, and made a hasty judgment.

It was an extraordinary first-class season for Bradman. He hit the first of his six triple centuries, an unbeaten 340 in 488 minutes for New South Wales against Victoria in Sydney. In 13 matches, he scored 1690 runs, still a record for an Australian season, at an average of 93.88 with seven hundreds.

The season launched the Bradman legend. For the next two decades, he was to dominate the cricket world like very few ever did. Kenneth Farmer reflected:

“He was Legend by the time the world realized he was news.”

(Excerpt from Indra Vikram Singh’s book ‘Don’s Century’).