Sporting contests to remember: Operation Sandstorm Day 1

Statistically, Sachin Tendulkar is the best batsman in the world. But statistics do not make a cult. Viv Richards may have only a few insignificant records to speak of, but many (including yours truly) consider him to be the best limited overs batsman the world might ever see before the Mayans come back to end it. And I say this despite having seen only grainy re-runs of his performances on television.

Similarly, the statistically-minded would rummage through a statistics engine and come up with the stat that the Master Blaster scored 446 runs at a mind-boggling average of 111.50 during the Tests against Australia in 1998. But the connoisseur would take greater pleasure in the memory of Tendulkar dancing down the wicket again and again to Warne, in a manner which would cause more damage to him than the cans of stale baked beans he brought along would to his stomach.

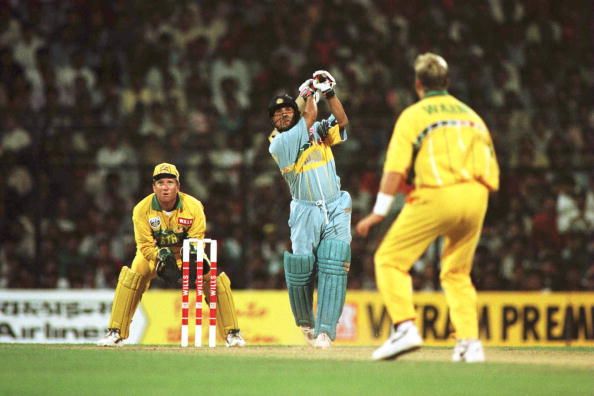

1996 World Cup: Sachin Tendulkar and Shane Warne in action

For me, the cult of Sachin Tendulkar began with Operation Sandstorm. I had heard tales of Old Trafford and a bloody nose but seeing is believing. In ’96, when Vinod Kambli cried his heart out on his kerchief, I empathised with him and put Tendulkar down as the main villain for whatever happened. Why not? After all, everything relied on him – it was his responsibility to get us across the line. With great power and skill and talent comes great responsibility. And all he does is make a wonderfully stroke-filled 65 – the highest score in the innings – before carelessly jumping out of his crease against that part-timer of part-timers, Jayasuriya.

He did nothing to redeem himself after that over the next year and a half. Or maybe he did but I never got to know – cable television in the 90s was considered to be a privilege either the richest or the bottom few of the class could have.

And then I read about his assault on Warne in the papers. Everyone said it was special but I clucked to myself – almost all the other Indian batsmen had scored runs in the series and the Aussies were comprehensively beaten. For me, Hrishikesh Kanitkar was the hero – someone who could win you a match by drilling a boundary across a patrolling Inzamam-ul-Haq with one ball to go.

Nevertheless, Sachin tried hard whenever I was there to see a match he played in – he failed with the bat but picked up his first fiver with the ball at Kochi in the first match of the Pepsi Cup against Australia and then produced a blazing ninety ball century to win a game later in the series. But he failed in the finals – as I had known he would.

The teams then moved to the Coca Cola Cup in Sharjah and I moved back to Shaktimaan. I kept in touch with the scorecards though and was duly informed that a young chap called Ajit Agarkar (who I thought was pretty promising on his debut) had induced a Kiwi collapse to win India a match. Then India lost to Australia where Tendulkar had made a little-more-than-a-run-a-ball 80 and my hero Kanitkar had valiantly battled for 35, but India had lost – as expected.

The last league match was only a formality and more so when I heard that the original finisher, Michael Bevan, got a chance to make one of his few centuries to power Australia to 284. India needed over five an over to even qualify for the finals and, adjusting for inflation, 250 back then would be closer to what 300 is these days.

To add to that,the Sharjah pitches were notorious for dying down as the game progressed – teams generally won the toss and batted first. And barring the top two, the rest of the Indian middle order had made more runs to the bathroom than in the series. It was impossible for India to win – after Tendulkar got out of course. For a change, my homework was done for the day and my parents were outside – two good reasons why I could go over to the neighbour’s house and watch the match without having to worryabout going to sleep early.

To add to that,the Sharjah pitches were notorious for dying down as the game progressed – teams generally won the toss and batted first. And barring the top two, the rest of the Indian middle order had made more runs to the bathroom than in the series. It was impossible for India to win – after Tendulkar got out of course. For a change, my homework was done for the day and my parents were outside – two good reasons why I could go over to the neighbour’s house and watch the match without having to worryabout going to sleep early.

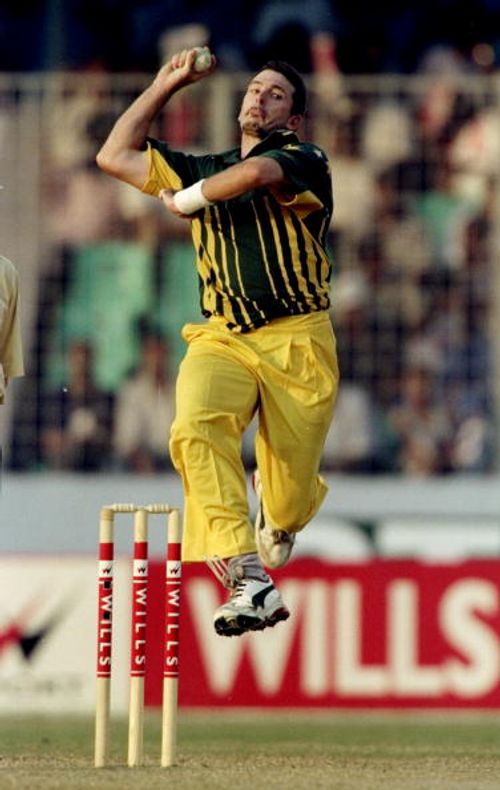

Australia, at that time, had two very good swing bowlers in Damien Fleming and Michael Kasprowicz – the latter would go on to attain fame in his second calling as a stubborn tailender who tried not to glove a delivery to the keeper and put England on course for their first Ashes victory in a very, very long time. The conditions and the lights helped them as they restricted India to 15 in the first five overs. I sighed – can we please not have yet another meek submission?

And then it happened. Two back-to-back pulls for six by Tendulkar and suddenly the Aussies were caught unawares. Ganguly followed it up with a sublime drive through the off-side as only he can do and suddenly the Indian chase had spluttered into life.

Not for long though. Very soon, Fleming got one to swing back into Ganguly’s pads. And then Azhar made a move which would partly redeem his later failings in my eyes – he brought on Mongia.

Before Dhoni, the closest thing to both a wicketkeeper and a batsman India had was Nayan Mongia. In those days, when all you needed to be an Indian opener was to turn up on match day, Mongia had smashed an incredible 152 against the same Australian side at Delhi in ’96. Something in the shimmering night air of Sharjah told me that he would click.

And click he did. By the time he departed after a brisk cameo of 35 which included one of the straightest sixes (off Tom Moody) human eyes will ever see, India were 93 after 20 overs – with Tendulkar still at the crease.

Azhar knocked the balls around in his usual languid style but the boundaries had dried up and he fell in an attempt to up the ante. Jadeja version 1.0 threw his bat outside the off-stump to give Gilchrist a customary chance to display his brilliance. In walked the pre-renaissance VVS Laxman. Not very much unlike a modern day Rohit Sharma – talented but intending not to show it.

And then came the sandstorm. 25 minutes of swirling dust and wind ate up four overs of India’s chase, leaving them a daunting challenge of a run-a-ball 96 to qualify and an almost improbable 135 to win. And with one last specialist batsman waiting back in the hut.

What followed was pure strategic brilliance. As Warne resorted to bowling quicker and flatter to limit Tendulkar’s scoring, the little man took to the medium pace of Kasprowicz and Steve Waugh from the other end. The return of Damien Fleming to the bowling attack did not change matters much as Tendulkar and Laxman brought the qualifying target down to 24 in 30, with the former bringing up his century in the process.

And then, disaster struck – almost. After a straight six had brought India closer, Tendulkar hit one straight to Damien Martyn who fumbled a regulation catch and, to add injury to insult, the ball continued its merry march towards the boundary ropes. The over eventually cost 15 runs and suddenly the target to win the match – 48 in 24 – was not that implausible.

Another boundary and over-boundary later, India had qualified and now were in sniffing distance of victory – 32 off 19. Tendulkar tried to tickle the last ball of the over down to the leg side for another boundary but only managed to get it as far as to Gilchrist. The umpire was not convinced but Tendulkar had made up his mind to walk and thus bring an end to an innings of 143 – with the last 43 coming at over two runs a ball.

What followed was the expected but massively heart-breaking anti-climax. Laxman and Kanitkar scratched around for 8 runs in the last 3 overs as India somehow managed to scramble to 250. It did not matter though in the long run – India was in the final and the Aussies were, at the very least, concerned of facing that man again.

But he hadn’t won the match after all for India, had he? And lightning, or even a sandstorm for that matter, would not strike in the same place twice. Or would it? I had two days to find out.