Sporting contests to remember: Operation Sandstorm, Day 2

A couple of days before he turned 25, Sachin Tendulkar played a knock which many before him would have given their right arm, right leg and most of their other digits for – an absolute blinder on a difficult wicket against the top dog with his team up against the odds. It had everything going for it – except for the fact that it was not a match-winning effort. Sachin Tendulkar took you to the finals; from there onwards, it was the Fat Lady’s job. Yuvraj Singh and Mohammad Kaif were still four years away in the making after all.

And Australia could – and would – slip up just once. This time they would be better prepared. India, at this juncture, were playing single wicket cricket – Sachin and the rest of the runners. The Indian middle order was softer and more sensitive than a rabbit’s underbelly.

Azharuddin had either spent his entire savings on Sangeeta Bijlani at Dubai Duty Free or was being plain and simple daft, or both, when he chose to field after winning the toss. Why would have been an under-question here.

However, the new kid on the block, Agarkar, and the slowest off the blocks (in terms of pace), Venkatesh Prasad, thought otherwise. Within no time Mark Waugh, Ponting and Moody had ensured that Mongia had justified his match fees by gifting him three sitters behind the stumps. At 26/3, the only way Australia could have looked is upward.

Gilchrist toned down his aggression and the ever-reliable Bevan supported him in a combative partnership, before both of them departed for an individual score of 45 each by the time the team’s total had reached 121. Other teams, by then, would have started planning for some “quality time” in the evening.

However, Steve Waugh‘s Australia, with the man himself out in the centre, had other plans. And with the support of the Bruce Willis lookalike Darren Lehmann (albeit with an extra layer of fat circumnavigating his centre), you had a pair who would bat freely or die hard with a vengeance. India’s part-timers leaked plenty of runs and the fielding lived up to its usual standards of ineptitude, as both batsmen scored 70 and the Aussies ended up on 272/9 – a total which they would have taken blindfolded at the toss.

After a brisk first over which cost 11 runs, Kasper, the not-so-friendly Aussie pacer, and the swinging Fleming were back to their miserly ways. Soon enough, after a couple of inside edges which almost took off a layer of varnish off the stumps, Fleming had his man as Ganguly’s weakness was exploited with a well-directed short delivery which had the southpaw miscuing a pull to Tom Moody.

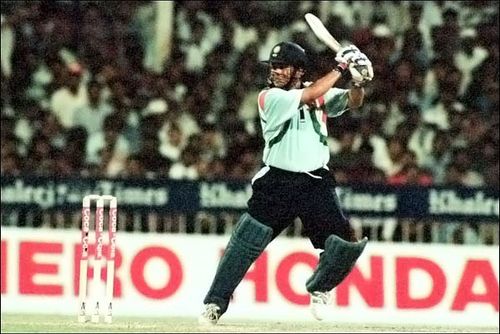

Mongia’s run at the top of the order was not done yet, and he was sent out again to prop up the scoring rate. Tendulkar, in the meanwhile, was warming up, and the likes of Moody and Mark Waugh provided the perfect cannon fodder for him to set the ball rolling. As in the last game, Warne tried to do something different by bowling around the wicket – and promptly got tonked over his head by Tendulkar for what can easily be described as the shot of the match. Thankfully for Warne, this match was the last of a long series of nightmares for him which had started with the Test matches in India.

Fleming was brought back, and he responded immediately by removing Mongia who had, by then, made his mark with an useful 28. Azhar was in his usual no-risk, no-loss mode and he provided the perfect foil for Sachin, playing percentage cricket and rotating the strike. In the process, Tendulkar brought up his second consecutive century and Azhar his fifty, while India inched closer to a famous victory. Not too many people remember this innings but this was closest to the best I have seen Azhar bat – and I wasn’t even born when he hit those three centuries in his first three matches. There is something about those Hyderabadi wrists which us mere mortals would fail to comprehend despite our intricate knowledge of bio-mechanics and all that yarn.

After his century was put out of the way, Tendulkar stepped up a couple of gears. Warne was smashed down the ground and through the covers; Moody over his head for a massive six which crashed into the sight-screen. Fleming, the best bowler on both sides by far, came back to bowl and it took him two frustrating LBW appeals and one miscued half chance to lose his temper. Kasprowicz was treated to greater ignominy; his first ball was deposited by Tendulkar onto the roof of the stadium.

In a bid to add some variety to the proceedings, Kasprowicz switched angles by going around the wicket and was promptly rewarded with a horrible umpiring gaffe. Tendulkar was gone – leg before wicket to a delivery which pitched outside leg. 25 off 33 – India could yet choke.

Azhar and Jadeja added 13 before umpire Javed Akhtar decided to add another feather to his cap of bloopers. Kasper was again the man to reap the rewards – this time by bowling a wide delivery, which, according to the umpire’s glance, had been glanced by Azhar. 12 to go and the house of cards was just teetering on the brink.

But my man Kanitkar was there. He had made a habit of winning matches set up by others and he was not going to let up on this one. Sachin had won India this match, but once again he had not finished the job he had started out to do and had left it to lesser mortals.

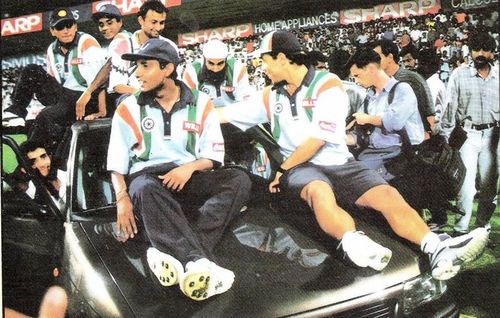

Oh come on – the cricket lover rebuked the cynic. India, in Tendulkar, had answered the queries of a strong Australian bowling attack, their critics and the elements over two midsummer nights’ dreams. This was not the time to be sardonic – this was the time to celebrate the sheer talent of an Indian whose average age was that of the country; this was a time to feel proud of being an Indian. This was the time to join the cult of Sachin Tendulkar.

This was the time the Bradman references started. If England ’90 had made a man out of a boy, Sharjah ’98 had made a Superman out of a man. Fifteen years hence the man’s legend is undiminished – his retirement from ODI cricket was almost elegiac for the national conscience.

Which is where I come back to the point I made in the first part of this series. Statistically, Sachin would better these scores – the 143 made in the match prior to this was his highest ODI score till his unbeaten 186 the following year at home against the visiting Kiwis, followed by the epoch making double century against the hapless South African attack over a decade later. But talk about Operation Sandstorm (or Operation Desert Storm as it is known in some circles) and cricket lovers light up like newly bought luminescent bulbs.

Sunil Gavaskar had taught his India how not to lose; Sachin Tendulkar taught an entire generation how to win. It was a lesson well imparted, as the likes of Virat Kohli have recently displayed. Bradman might be the greatest batsman in the world, but he had his Invincibles to win him matches; Sachin often had no one but himself, and it is a tribute to his tenacity that he carried a lifelong burden of being labelled as someone who is not a match-winner. Everything said and done, no one can take those two nights in the desert away from the Little Master.