Sri Lanka Cricket’s well-kept secret: The struggling spin bowling department

Being a tiny island, Sri Lanka, has managed to classify quite a few of the world’s best kept secrets: One, Sri Lanka has the third highest suicide rate in the world; Two, volleyball is Sri Lanka’s national sport, not cricket. A third addition to the list might be the alarming fact that Sri Lanka has stopped producing good spinners.

Yes! This might be a bolt from the blue for many for the emerald island has, in the past, had the tradition of producing top-notch spinners in the ilk of Somachandra de Silvas, Don Arunasiris and Muttiah Muralitharans, and in the times just passed had the ritual of producing enigmatic spinners like the Mendises, the Akila Dhananjayas and the Senanayakes.

The country has been reveling in its past glory of producing good spinners, so much so that it is still oblivious to the fact a permanent successor to Muralitharan has not been found as yet. As typical for a subcontinental team, Sri Lankan bowling department’s sole focus has been producing good fast bowlers so as to increase the chances of survival overseas. But in an attempt to strengthen one discipline, the other discipline has been completely glossed over resulting in the neoplastic degeneration of spin bowling in the country.

The decline has been so subtle that it has managed to escape many an eye, but it has culminated to a point where Sri Lanka would enter an ICC tournament in the subcontinent without any serious advantage over the non-subcontinental teams in spin bowling. Truth be told, England, South Africa and the West Indies have better spin bowling resources in their lineup than Sri Lanka.

Rangana Herath, the aging and the debilitated left-arm spinner, is almost 38. The next best spinner in the island, Dilruwan Perera is just 4 years younger than him. There is no promising spinner in the skyline and the 25-year-old Jeffrey Vandersay seems to be a forsaken soul in a world where old men’s age is just a number while a young man’s age accounts for inexperience. Sri Lanka is not willing to invest in its young spinners and the results are there to be seen.

The unflattering numbers

Since Murali’s retirement from international cricket, Sri Lankan spinners have averaged 21.35 in T20Is, 37.24 in ODIs and 32.73 in tests. The average in T20Is is the third best among all teams, thanks primarily to the manifestation of ephemeral mystery by Ajantha Mendis and Sachithra Senanayake. In tests, Sri Lanka is a distant third to India, much of which is the result of the canny work of Herath. In ODIs, however, Sri Lanka have the sixth best average and even the West Indian and South African spinners have done better. The English spinners also boast of barely the same average, which shows how bad the Sri Lankan spin bowling has been ever since the great maestro called it a day.

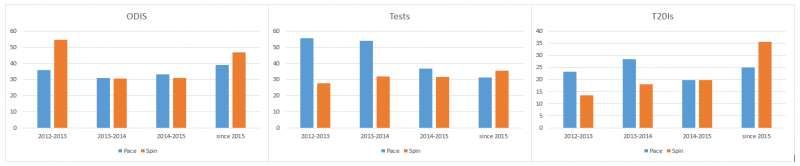

But these are numbers across almost five years. If the statistic is broken down by years, then a clear aggravation of the problem can be observed. The delinquency has reached a stage where in the last one year, Sri Lankan spinners have averaged 33.85 in tests, 35.65 in T20Is and 50.27 in ODIs. The fast bowlers, in contrast, have averaged 29.65 in tests, 24.91 in T20Is and 38.33 in ODIs. Although it could be argued that Sri Lanka could be happy with the unprecedented efforts of the pacemen, the fact is that this is more of a result of the degeneration of spinners than anything else. The gap between fast bowlers and the spin bowlers has gradually shrunk and has climaxed at Sri Lanka being forced to rely on its below par pace stocks to win matches.

Across all formats, a steady decline in the gap between fast bowling and spin bowling can be observed, with pace emerging our dominant weapon over spin since 2015.

Since 2015, Sri Lanka’s spin bowlers have done worse than both Australian and South African spinners in tests. They have been the fifth best spin blowing side in tests in the world, despite playing most of their tests at home. In ODIs, only the West Indies have done worse than Sri Lanka in spin bowling with the islanders averaging a whopping 46.98. In T20Is, Sri Lanka is the third worst with an average of 35.65.

Sri Lanka’s lottery with spinners

Since Muralitharan’s farewell, Sri Lanka has tried 15 spin bowlers, the most by all test playing teams. The second highest number of spinners used is 11, which goes on to show the lack of vision among the selectors when selecting a spinner. Sri Lanka’s main spinner in these 5 years has only played 48.2% of all matches across all formats, the lowest by any team (for teams that play two different spinners for tests and LOIs, the aggregate of their matches was considered).

The management of the team never really tried to groom a spinner alongside Murali and after his retirement, it was pure luck that brought Herath into the team. When Herath was brought back, the team never had any long term plans for him. Muralitharan was injured during a home test series and Herath was called back abruptly from England. Since then it was the chubby left-armer’s sheer intransigence that helped him claim a permanent position in the test side.

Herath stood up as the then selectors were playing roulette among Suraj Randiv, Ajantha Mendis and Herath himself. The southpaw’s resurrection is pristinely out of his own faculty and not due to the carefully devised plans of the management.

In limited overs cricket, the story has not been so rosy. Sri Lanka’s experiment with Suraj Randiv came to an abrupt end, that too after he picked up a fifer against England and soon he was replaced by Seekuge Prasanna. In the meantime, Dilruwan Perera managed to play a slew of T20Is but was then ignored until 2014. As Prasanna’s leg breaks failed to turn, Sachithra Senanayake was handed over a debut and the selectors lost patience with him mid-way during 2012.

With the 2012 WT20 soon approaching, the management started handing over an ill-planned spree of debuts. Sajeewa Weerakoon played just the two matches and Kaushal Lokuarachchi managed only two T20Is. Such was the void for a good spin bowler, in a match against Pakistan Jeevan Mendis, despite being a batting all-rounder, played as the specialist bowler.

After the 2012 SLPL, Ajantha Mendis was brought back into the team. The rise of Akila Dhananjaya promised to allay Sri Lanka’s spin bowling woes, but after the WT20, he went back to domestic cricket and never returned back.

As Mendis too started fading away, once again the team resorted to their old but failed ploy of taking pot luck with the three spinners, Ajantha Mendis, Seekuge Prasanna and Sachithra Senanayake. In a T20I game against New Zealand Ramith Rambukwela, a spin bowling all-rounder was given a debut.

The prelude to the WT20 in 2014 saw Sri Lanka trying out Chathuranga de Silva, but he too flattered to deceive. In 2014, Senanayake emerged to be Sri Lanka’s lead spinner in limited overs cricket, but a crooked action threw him out of cricket for a while.

Sri Lanka again resorted to using their tested-and-failed spinners in a loop and even added Jeevan Mendis to the fray. Lakshan Sandakan, a chinaman bowler, was drafted into the squad for the ODI series against England at home but he played no games.

After having both Seekuge Prasanna and Sachithra Senanayake fail in the 2015 World Cup and Herath being left out with an injury, Tharindu Kaushal made his debut in the quarter-finals of the World Cup. Sri Lanka was knocked out by South Africa and Kaushal played no more ODIs.

Sachith Pathirana was handed over an ODI cap against Pakistan in 2015 but his dismal left-arm spin could not keep him in the side for too long. Jeffrey Vandersay was handed over a debut in T20Is and having not been given adequate opportunities, he was cold-shouldered too.

Where does the problem lie?

The majority of the problem lies with the Sri Lankan domestic structure. Each of the fifteen highest wicket takers in the recently concluded domestic first class match tournament was a spinner. Sachith Pathirana, a spinner who struggled to spin the ball in international matches, picked 45 wickets, the fifth best overall, which shows the frail nature of the pitches used in domestic matches. If even a run-of-the-mill spinner is going to be made to look like a grenade hurled at domestic level, then there is no surprise the quality of spin bowling finds itself in the abyss.

The lack of persistence shown with spinners has also come haunting. Suraj Randiv was ousted for no apparent reasons and had he been persisted with, Sri Lanka might have had most of their griefs scuppered. Soon after having his doosra banned, young Tharindu Kaushal was replaced by Dilruwan Perera, albeit Kaushal having proved his wicket-taking ability with his off-breaks alone. Jeffrey Vandersay’s stay in the team was short lived and he is someone who should be persisted with at international level. The management seems to be wanting prompt results with its spinners and since they failed to groom a spinner during Murali’s days, they have no choice but to wait.

The team has also been reluctant in trusting young spinners and given the quality of the domestic tournaments, it is very difficult to judge a player’s potential based on his numbers alone. The fact that the 34-year-old Dilruwan Perera is preferred over the Kaushals and the Lakshan Sandakans, lays bare the fact that the team is paranoid about playing rookies.

The team also has the propensity to prefer stop-gap solutions over long-term solutions. The team’s vision is only as far as the following game. With that kind of a thought process, the problem can hardly be countered.

As is the case with most things, the first step to finding a solution is to acknowledge that there is a problem. The spin bowling woes are yet to come under the scanner and the cricket populace in the island seems to be still basking in the traditional stereotype of being a spin-dominant team. By the time finally the nation realizes its real problem, the team might have reached the rock bottom and a volte-face might almost be impossible.