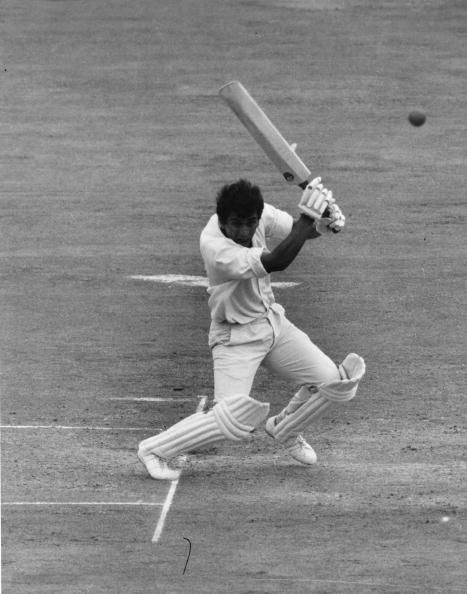

Sunil Gavaskar vs The West Indies: Part 1

It was Gavaskar

The real master

Just like a wall

We couldn’t out Gavaskar at all

Not at all

The West Indies just couldn’t out Gavaskar at all

(Lord Relator, 1971)

It was 1971, and Trinidadian calypsonian, Lord Relator (Real Name Willard Harris), was so impressed by Sunil Gavaskar’s run scoring during India’s visit to the West Indies that he was moved to immortalize him in song. As a boy of six and not yet totally consumed by the great game, I remember wondering, upon hearing the commentary on radio when my mother would tune in, why so many of the Indian batsmen were named Gavaskar. It appeared to my untrained ear that there had to be more than one Gavaskar, as one batsman could not have been occupying the crease for such extended periods.

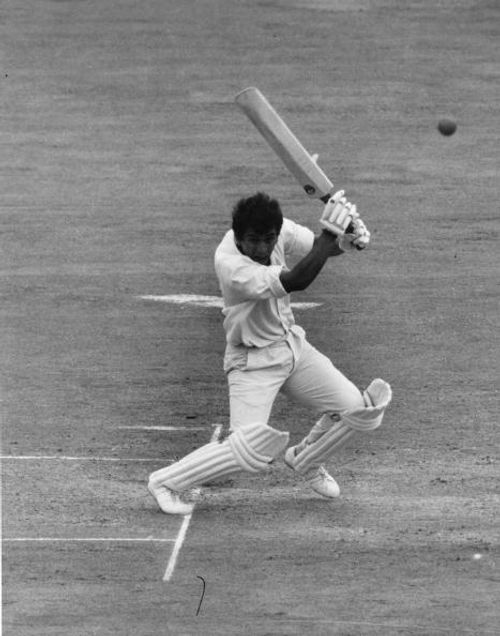

The little Indian, standing at just 5’5”, ran roughshod over the home team’s bowlers on his first venture into Test cricket, leading the visitors to a 1-0 series victory. The 21-year-old from Mumbai (then Bombay) missed the first Test in Jamaica because of an infected fingernail, but reported for action for the second Test at the Queens Park Oval in Trinidad, which India won, and plundered 774 runs in four Tests at a stunning average of 154.8 with four hundreds. The West Indians, recently shorn of the pace of Wes Hall and Charlie Griffith, could find no way to restrain the opening batsman. His series of scores were almost unbelievable: 65, 67*, 116, 64*, 1, 117*, 124 and 220.

The hosts were so frustrated about their failure to stem Gavaskar’s run-flow, according to Clive Lloyd in Living For Cricket, that discussion of tactics to dismiss him consumed much time in team meetings. At one meeting before the last Test, Lance Pierre, match manager and former test player, offered a this far-out idea:

We should, Lance said, bring him on the front foot, keep him quiet and then serve him up with a waist-high full toss which, in his anxiety to get it away, he would hit it to deep square leg for a catch. (pp.48-49)

Lance’s plan was never attempted, and Lloyd felt this was an indication the West Indies was at their wit’s end.

The Jamaican speedster, Uton Dowe, was introduced for the fourth Test in Barbados and elicited Gavaskar’s only failure for the series with a short, fast, rising delivery that he tried to hook. Elated at the little man’s dismissal for a single run, the home side was heartened by what they accepted as a hint that the thorn in their side could be plucked out by pace and hostility. But by the second innings, the opener was back to his best with 117*.

Returning to the Queens Park Oval in Trinidad for the last Test, Gavaskar was afflicted by a horrendous toothache that caused him sleepless nights and severely restricted his diet. Fearing that an extraction might have led to complications that would have prevented his participation in the Test, the manager refused to allow him one, and so the run-machine had to carry the pain into the game. Yet, as Gavaskar constructed two masterful hundreds in the game, one of them a double, he seemed serenely at ease, apparently bothered by neither bowling nor toothache.

The little master left the West Indies triumphant. Nothing, it appeared, could stop him from conquering the cricket world. But he was not able to maintain the super-human levels he rose to in his first Test series. In 13 further Tests, including two against the West Indies in India, he added just one more hundred, and it took a return to the Caribbean in 1975-76 for him to return to something approaching his best form.

He started off slowly in Barbados, scoring 37 and 1 in a game that the West Indies won, but gathered steam with rock-solid 156 against the might of Michael Holding and Andy Roberts in the second game in Trinidad.

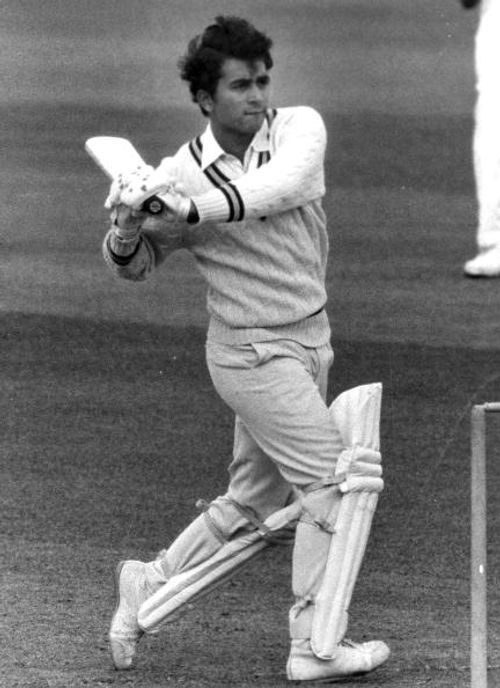

The third Test, which was scheduled for Guyana but switched to Trinidad due to rain, ended with India defeating the West Indies by way of a record-breaking run chase. The West Indies declared with six wickets down in their second innings, setting India 406 to win — a target India achieved for the loss of just four wickets. Gavaskar and Gundappa Viswanath made hundreds, while Mohinder Amarnath batted for a long time, scoring 85, as India hardly broke sweat in gaining a remarkable victory.

The West Indies had entered the game on the spin-friendly Queens Park Oval track with three spinners. But the 100-plus overs among them yielded only two wickets, with the other two being run-out. Captain Clive Lloyd was livid, and it is here, according to legend, that the final seed was planted that grew into what became the most effective force in cricket history – the four-pronged pace attack. Spinners were never relied upon again.

The final Test in Jamaica was wrapped in controversy. Michael Holding, bowling like the wind and aided by an untrustworthy Sabina Park strip, posed serious threat to life and limb. Several batsmen were struck; two retired hurt in the first innings, and captain Bishen Bedi declared the first innings closed with four wickets still intact for fear of injuring his bowlers. Gavaskar made 66.

The final Test in Jamaica was wrapped in controversy. Michael Holding, bowling like the wind and aided by an untrustworthy Sabina Park strip, posed serious threat to life and limb. Several batsmen were struck; two retired hurt in the first innings, and captain Bishen Bedi declared the first innings closed with four wickets still intact for fear of injuring his bowlers. Gavaskar made 66.

The second innings was closed at 97 with just four wickets down and five batsmen listed absent hurt. The only score of note was a highly courageous 60 from Mohinder Amarnath. The West Indies then made the 13 required for victory without bother, and, with victories in Barbados and Jamaica, won the series 2-1.

Gavaskar felt the West Indies fast men had gone overboard with their short-pitched bowling in Jamaica and it is reported that he complained to umpire Ralph Gosien. He was also utterly disgusted by the behaviour of the crowd. In his autobiography, Sunny Days, he recalled,

To call the crowd a ‘crowd’ in Jamaica is a misnomer. It should be called a ‘mob’. The way they shrieked and howled every time Holding bowled was positively horrible. They encouraged him with shouts of ‘Kill him, Maaaan!’ ‘Hit ‘im Maan!’, ‘Knock his head off Mike!’ All this proved beyond a shadow of doubt that these people still belonged to the jungles and forests, instead of a civilised country….

Gavaskar went on to refer to the spectators as barbarians thirsting for blood and opined that they belonged in trees.

This response, remember, was not expressed in the heat of battle. This was what Gavaskar came up with after he had much time to reflect and many in the West Indies did not appreciate the sentiments expressed by the great batsman.

Despite the hardships in Jamaica, Gavaskar must have been reasonably satisfied with his own performance in the West Indies. He was now the owner of a batting technique as solid as any the game had seen, and was poised to achieving a level of consistency that he had found elusive up till then.