Tales of the brave

Man is the only species blessed with courage- that voluntary emotion which reigns in the persuasions of instinct and at times, rationale. Not everyone, though, is blessed with equal opportunities to demonstrate their mettle. Those who do are respected and admired, remembered and written about. Courage propels man to do extraordinary things, against the most insurmountable odds. A sport has been defined in many ways, but it is also an opportunity. A battle against everything a sportsman fears, and if he comes out on top, the sport itself is the real winner.

Sometimes, these battles acquire magnificent proportions. Courage has propelled these sportsmen to glory and beyond.

Courage to face the Unknown

October 14, 2012

He stood at the edge, and looked. The azure skies that had defined the past two hours of his life had given way to inky blackness. Beneath him – 128,100 feet below – home was waiting. The world spun slow and brilliantly blue. Apart from the static-laced voice in his earpiece that had kept up a relentless flow of instructions and words of encouragement ever since he’d begun his journey, there was absolute silence. No roaring winds, no lusty cheers. Not yet.

The cables were released. Inside the specially designed futuristic pressure suit, he was in a world of his own. A layer of frost had formed on his visor that threatened to abort the whole thing-again.

“Start the cameras and our guardian angel will take care of you.”

“Sometimes you have to go really high to see how small you are”, he responded,” I’m coming home now.”

And jumped.

Is it a bird? Is it a plane? No, it’s Felix friggin’ Baumgartner, and he’d just become a human meteorite. He was free-falling from a height five times that of a certain Mt. Everest.

Immediately after he’d dropped into what was essentially space, he began to spin like a top. This wasn’t unexpected, but extremely dangerous. Let me put it this way- you begin spinning beyond a certain rate while falling at those speeds, the blood in your body rushes to your extremities and comes out through the only outlet it gets- your eyeballs. But you wouldn’t see that, because you’d be dead by then.

There was no way for his ground-crew, the Red Bull Stratos Space Diving Project, to know if he was dead or alive. This guy was either going to be history or make it.

Meanwhile, he managed to steady himself from the spin, and accelerated at impossible rates to reach a top-velocity of 1342 km per hour. That’s Mach 1.2. That’s faster than the speed of sound. If you’ve seen Indiana Jones crack his whip, you know what a sonic-boom is. This man was travelling faster than the one he himself was generating. Lockheed-Martins do that, and they can circumnavigate the globe in less than a day.

Four minutes and nineteen seconds into his plunge, he deployed the parachute, and that was the moment when, reportedly, his mother Ava breathed. She continued to cry even as 8 million people broke into ecstatic cheers across the world when he touched ground, dropped to his knees and punched the air.

Mike Todd, the team’s life-support engineer had been the last one to see him as he’d stepped into his capsule for the ascent. “OK, see you on the ground, buddy,” Todd had told him. Todd was the first to receive him back on earth.

The glories keep piling up, but Baumgartner has earned every last one of it. He’d put in five years of dedicated concerted effort with The Red Bull Stratos team for the ten minutes of the Looney Toons-style spectacle. Twenty-five years of skydiving had brought him to the zenith of the art, and he’d wrested it with both hands. Defying fear, death and imagination, he established records for the highest manned balloon flight and the fastest speed of free-fall.

The minute he caught his breath, he announced his retirement from daredevilry. Now I am no fan of the Afridi Retirement System, but Baumgartner’s got a ‘Born to Fly’ tattoo on his arm. This doesn’t end here.

Courage against Infirmity

July 28, 1992

C.N. Janaki was at war, with the sea and her own body. It had taken her half a decade of preparation and a lifetime of courage to get here, and she was not remotely planning on giving up. The English Channel, however, was merciless. Waves lashed at her and currents threatened to put her off-course, if not drag her down.

She wasn’t alone, though. Her relay-team, a bunch of anxious Americans who’d seen fit to name themselves ‘Janaki’s Meantime Express’ in her honor, followed closely in a boat. People had drowned in the Channel before. Ever since the Englishman Matthew Webb had swum the entire 35-kilometer course in 1875, people had been popping up from all corners of the world to emulate the feat. The Channel is to swimmers what The Everest is for mountaineers- brutal, grueling and alluring.

Janaki was in a world of pain, but kept pushing on. Her team-mates watched in amazement as they saw her negotiate the rough waters with tenacious poise.

For this was no ordinary woman.

C.N Janaki had been afflicted by polio at age two, which had effectively made her legs useless. They simply trailed along as she used her upper-body to cleave through the waves. She’d only learnt to swim as late as thirty years-old. Four years of hardcore training in Bangalore plus another in the Arabian Sea under a National Institute of Sports coach paid off, and she became the first disabled person to part-swim the English Channel.

Her original ambition had been to go solo, but the English Channel Swimming Association rejected her repeated requests to permit her the opportunity. Stella Streeter, a renowned Channel coach who trained her in the days preceding the actual attempt said Janaki was the bravest woman she’d ever met.

At the end of her sanctioned time of 2 hours, after she’d coughed out the brine and peeled jellyfish and seaweed off her lifeless legs, she had this to say: I strongly believe that the word ‘impossible’ is applied to something that has not been tried.

Courage in the face of Oppression

10 February 2003

“In all the circumstances, we have decided that we will each wear a black armband for the duration of the World Cup. In doing so we are mourning the death of democracy in our beloved Zimbabwe. In doing so we are making a silent plea to those responsible to stop the abuse of human rights in Zimbabwe. In doing so, we pray that our small action may restore sanity and dignity to our Nation.”

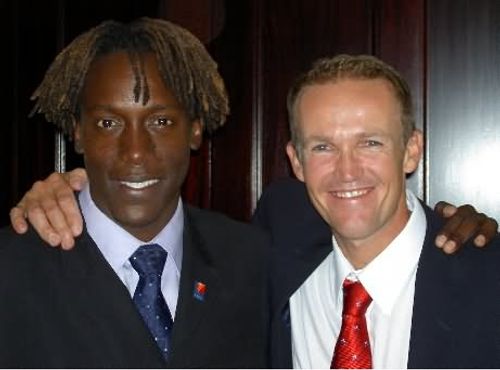

This was a statement released by two cricketers on this day who felt it their responsibility to stand up for what was right. Sheer patriotism prompted these gentlemen to exhibit an entirely new manifestation of courage in the face of persecution.

Andrew ‘Andy’ Flower and Henry Olonga were two of the greatest cricketers Zimbabwe had ever produced. With over 4000 Test runs in 63 matches and over 6000 in the 200-odd ODIs that he played in a career spanning a decade, Flower was widely considered to be the best wicket-keeper batsman of his generation, along with Adam Gilchrist. He holds the maximum of Zimbabwe’s batting records, and is the only one from his country to figure in ICC’s ‘Top 100 All-time Test Batting rankings’.

Henry Olonga had already made history on his debut in 1995 when he became the youngest player to represent Zimbabwe at 18 years old and also the first Black person to play for the country. The right-arm fast bowler holds the record for the best bowling figures by a Zimbabwean and has decent statistics against his name.

Zimbabwe in 2003 was (and continues to be) a country ravaged by violence, hyper-inflation and virtual absence of civil rights. President Robert Mugabe is, for all ends and purposes a dictator. Following a string of failed economic policies (land-grabbing was actually made legal and mandatory in some areas), international sanctions were imposed against it, causing a Civil War-esque situation in the country, staggering unemployment levels and thousands of refugees fleeing the country.

Flower and Olonga decided to protest against the Mugabe regime during the Cricket World Cup in the simplest of ways- they wore black armbands during the matches. The method was an overwhelming success- they caught the world’s attention- but in effect, they had signed their own death sentences.

While internationally lauded as heroes, back in their country both were charged with treason, which is punishable by execution.

“In the three or four weeks after we made our stand they got really angry and I had never felt so vulnerable, but we believed the government wouldn’t do anything to us while there was a watching world,” Olonga recollected later. “One of Mugabe’s ministers said to me, ‘Wait until the World Cup is over’.”

The nightmare had only just begun. The danger to their lives had been real and immediate. Both of them narrowly escaped being arrested in South Africa by Zimbabwe security forces (during CWC-2003), fled the country and went into hiding for a while. They would never return to their homeland.

Much has changed for them since- Andy Flower is now the coach of the England cricket team and is being hailed as one of the best ever while Olonga lives in London where he has taken firm footholds into the music industry. But they had to forego the one thing that they loved most- play for their national side.

“I can look in the mirror and say, ‘I believed in something. I stood up against a vile wicked dictator’, it changed my life for better and worse, but the good outweighs the suffering and sacrifices.”

“I would say we didn’t achieve a lot in practical terms no, but knew we wouldn’t. Our goal was to do something, even if we changed perceptions in a small way, to jog people out of their apathy.”

These are just three of a hundred extraordinary stories of courage and conviction demonstrated by sportsmen on the field and off it. Every once in a while, a fire is lit within an individual, and a hero is born. There are two kinds of sportsmen in the world: the ones who face defeat and the ones who overcome it. And then we see a third kind shining through the crowds – the ones who wouldn’t be defeated.