Test match batting, the Geoffrey Boycott way

E. H Carr argued that history is a “series of accepted judgements” based upon what the historian chooses to believe. It is the interpretation and selection of facts as well as the context attached to them that make up the body of knowledge. As such, the notion of objective historical facts selected without bias is flawed. Historical facts while necessarily accurate, are also selective. (Carr, 2001:5)

A cursory Google search reveals that Carr and Geoffrey Boycott never crossed paths. But had they done so, Boycott would have probably recognized a kindred spirit in him and slapped him on the back.

Boycott was a year away from making his first-class debut when Carr’s seminal ‘What Is History?’ was published, but the ideas discussed in it could easily be applied to his career and the oft-discussed but ill-defined ‘Geoffrey Boycott School of Batting’. Boycott’s style of batting divided opinion, and interpretations of it were polarized enough to ensure that there is a wealth of opinions to sift through while discussing it.

Before discussing his style of batting or what he achieved in the career, it is important to understand Boycott the man. William Wordsworth was decidedly not thinking of Boycott when he wrote that “The Child is the father of the Man”, but I put forth the opinion that Boycott the batsman was born out of the characteristics of Boycott the man.

What some saw as sacrifice and self-denial, others saw as selfishness

Boycott’s batting was defined by a bloody-minded focus, innate self-belief and a never-give-up, stiff-upper-lip frame of mind. The same qualities that allowed him to amass 8,114 Test match runs drove him in his successful quest to repel the menace of throat cancer long after his playing days had ended.

The same man who divided opinion in his role as a straight-talking commentator due to his refusal to compromise on his beliefs sat out three years in the prime of his career, yet managed to play 108 matches and finish his career as the leading run-scorer in Test match history at the time.

An unyielding, bloody-minded certainty in his beliefs drove both Boycott the man and Boycott the batsman. The harsh lessons learned from his frugal upbringing in the mining village of Fitzwilliam stood him in good stead for the challenges of Test cricket.

Both his personal and professional lives were marred by adversity; his spleen was removed at the age of 8 when he fell on a mangle, and at the age of 16 he believed his career was over before it had even begun when he was told he had to wear glasses while batting. A lesser man, or rather boy, may have quailed, but Boycott was made of sterner stuff. He took everything in his stride and soldiered on, his desire and intestinal fortitude overriding the limitations of his health.

Boycott scored runs, divided opinion and made occasional trips to the hospital due to illness brought on by his lack of a spleen. He was down a lot; sometimes he was knocked down by others and sometimes he fell down due to his refusal to compromise. But he always got back up.

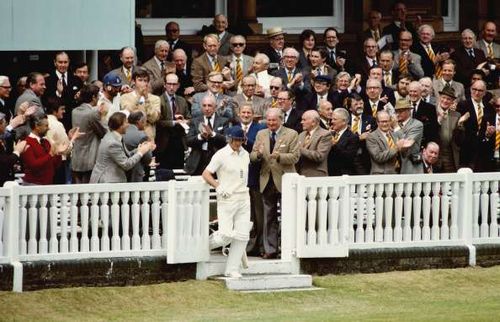

His batting is revered and loathed in equal measure; what some saw as sacrifice and self-denial, others saw as selfishness. However, say what you will about the man, but he knew how to make a statement; he ended his self-imposed three-year exile by scoring his hundredth first-class hundred in an Ashes Test match, on his home ground of Headingley.

Like Carr’s history, recollection of Boycott the batsman is coloured by the interpretation of the person discussing it. His defenders point to the fact that only 20 of his 108 Tests ended in defeat, while his critics argue that he was selfish and was once dropped from the Test team for scoring too slowly. Yet, the score he made on that occasion was a marathon 246*, 82 more than the opposition managed in their first innings.

Only 20 of Boycott's 108 Tests ended in defeat, but only 35 ended in victory. Those are absolute truths; accurate historical facts that cannot be refuted. How they are interpreted colour the player portrait of Boycott the batsman.

The Geoffrey Boycott School of Batting

It is difficult to pinpoint what the defining characteristic of the ‘Geoffrey Boycott School of Batting’ is. I suppose that depends on what strikes you the most about his batting. Almost all reflections and recollections of his batting seem to suggest that it was about as entertaining as watching grass grow or paint dry. Yes, as an opener his first job was to take the shine off of the new ball.

For a manner of comparison though, Virender Sehwag - a man whose batting philosophy was the antithesis of Boycott - ended up with 472 more runs in four less games with an average 1.62 points higher. Does that mean that there was a better way for Boycott to have approached his job?

Perhaps there was a different way he could have gone about his business, but those statistics are somewhat mitigated by the fact that unlike Sehwag, Boycott batted in the era of uncovered pitches and played a vast majority of his games on treacherous, swinging wickets.

While that does not change the fact that Sehwag’s method of belting the new ball to get the shine off of it was cruder, and arguably just as effective, those of Sehwag’s ilk - David Warner, Michael Slater and Roy Fredericks - are considered anomalies in Test cricket because of how rare their kind is. If they are considered deviations, Boycott is assuredly the mean; the prototypical Test match opener.

However, dubbing the entire genre of staid Test match openers who believe that defence is the first form of attack as students of the ‘Geoffrey Boycott School of Batting’ is unfair for a number of reasons. Firstly, Boycott was far from the first opener to employ that philosophy, and nor was he the most successful; that accolade must surely go to Sunil Gavaskar. Secondly, to do so would be doing Boycott a disservice.

In recent vintage, Ed Cowan carved a respectable if unspectacular career for himself by batting time. However, while Cowan regularly brought up centuries in terms of balls faced, he rarely - if ever - pushed on to make a defining score. Boycott scored 22 centuries in his career, averaging out to a century every four games. He may have been boring, he may have soaked up time, but he translated that labour into match-defining runs.

Another example that springs to mind is Nick Compton. His last name may have been Compton, but his approach at the crease was nothing like the one applied by his grandfather. He believed in getting stuck in and like Boycott before him, decided early in his career that less is more in terms of strokes played.

Unlike Boycott though, the shackles imposed on his batting spread to the mental aspect of his game as well, and there developed an incongruence between his natural game and the shot selection he employed.

The beauty of Boycott lay in the fact that he was proud to be a tortoise; he had supreme confidence that his slow and steady approach would win the race. Compton’s first spell of Test Cricket ended because it was believed that England needed more proactive, dynamic players.

Desperate to make amends the second time around, he learned that just like it was impossible for the Ethiopian to “change his skin, or the leopard his spots” (Jeremiah 13:23), so it was impossible for a tortoise to suddenly become a hare.

Compton’s second spell in Test cricket ended when he tried to force the agenda and play too many shots - when he strayed away from his natural, defensive, solid game. Unlike Compton, Boycott never tried to be something he was not. It was the mental security resulting from his absolute conviction in his beliefs that allowed him to thrive by playing the way he did.

While bloody-minded defence and forcing the bowler to get you out rather than getting out yourself to a low-percentage shot are hallmarks of Boycott’s style of batting, part of the reason he was difficult to dismiss is because he did not feel the pressure of having to score quickly. He was always in control of the situation and he was the one dictating the pace of play; even if it was a slow pace.

It is not about getting bogged down, it is about getting the bowlers bogged down

In 2008, with a century for the taking at Perth, Rahul Dravid got himself out for 93. Having repelled Brett Lee, Mitchell Johnson, Shaun Tait and Stuart Clark on the fastest wicket in the world, he fell to Andrew Symonds of all people. Furthermore, it was a wild hoick in an attempt to force the pace that got him out.

In the period of play before his dismissal Dravid batted well within himself, patting the ball back here, leaving a ball there. All extravagant shots were cut out. There were no low-percentage shots before the slog, but the slog was brought on due to the mounting pressure caused by not scoring quickly. As Ian Chappell put it while doing commentary at the time, he was letting “part-timers dictate terms”.

Until he got out, Dravid was batting in a very Boycott-esque manner. However, while Boycott was dogged in defence, he never allowed himself to get bogged down to the point that he would play a stupid shot in order to try and release the pressure. In fact, one could argue that because he chose to play in that way of his volition, there was no pressure.

Where Dravid’s innings veered from the ‘Geoff Boycott School of Batting’ was in terms of dictating the pace of play. Boycott batted slowly because he chose to, not because the bowling dictated that he did so.

That Boycott’s stroke play or lack thereof was borne out of self-denial is proven by the fact that in the 1965 Gillette Cup Final he scored a scarcely believable 146 with 15 4s and 3 6s. Six years before the first one-day international and 10 years before the first World Cup, that was an astronomical display of stroke-making.

There's another piece of the puzzle getting filled; playing within yourself by choice.

The anti-Boycott - Virender Sehwag

It is almost poetic. The man named Boycott chose to boycott most of his strokes. Therefore, to qualify for the ‘Geoffrey Boycott School of Batting’, a batsman has to possess all the strokes but should choose not to play them. Building upon that premise, the next batsman I would like to put forward for consideration for entry is none other than the anti-Boycott himself - Virender Sehwag.

There would no doubt be some consternation at this choice. Granted, there is a vast incongruity between the two. Where Boycott went right, Sehwag galloped left. One believed first and foremost in scoring enough runs to ensure that his team never lost the game, the other had the ability to change the course of an entire match in a frantic session. One man was meticulous to the point of obsession, the other was laid back and believed in the simple batting mantra of “see ball, hit ball”.

Boycott relied on a textbook batting technique, Sehwag relied on incredible hand-eye coordination. It would appear that apart from forthrightness, the two have absolutely nothing in common. Yet, the fact remains that Sehwag, the man who once took a dig at Boycott by saying “Boycott can say what he wants.

He once batted the whole day and hit just one four”, once played an innings that went against every fibre of his batting philosophy. It was an innings that saw him bat an entire session without hitting a single boundary.

This is the same man who single-handedly derailed England’s hopes of defending a 4th innings target of 387 in one manic session. The same man who once bludgeoned 284 in a day. The same man who hammered the mighty Australians all around the MCG for 195 in one day.

Granted, there were extenuating circumstances to this torturous Sehwag innings I'm talking about; India were trying to draw the final Test match of the acrimonious 2007-08 tour. But having returned to the team the previous Test after Indian cricket had seemingly passed him by, Sehwag exhibited great self-restraint to bat through most of the last day at Adelaide to score an ultimately match-saving 151.

Technique be damned, as far as self-denial and mental strength went, this innings was straight out of the ‘Geoffrey Boycott School of Batting’.

For a man who loved to dominate as much as Sehwag, it was doubly impressive. It was the cricketing equivalent of taking a hard-core non-vegetarian to a buffet with every type of meat imaginable, and asking him to eat salad. It was Michael Schumacher and Sebastian Vettel being asked to drive in Delhi traffic. It was absolutely the last thing you would expect from Sehwag; that he did so and still managed a strike rate of almost 64 in the innings reinforces how great his self-denial was for that one session.

Another innings by a great Indian player on a tour of Australia characterized by great mental strength and self-denial comes to mind almost immediately here. Sehwag batted an entire session without hitting a boundary, but this man scored an unbeaten double century without playing a single cover drive. The man in question was Sachin Tendulkar, and the setting was the fourth Test match at Sydney in 2004.

Having been dismissed cheaply in previous games that series by nicking behind the wicket, he decided to shelve the cover drive for the time being. And just like that, he crafted an innings studded with every other shot in the book, and made the small matter of 241* - batting close to 10 hours.

Players have decided to shelve strokes in the past, but that is usually restricted to not playing extravagant shots and is specific to a particular context in the game. For example, an opener on a green track may decide not to play anything that isn’t on his stumps. A batsman on a dustbowl may decide not to hit against the spin early on in his innings. But to shelve the cover drive for almost 10 hours, even after crossing 150, is something else entirely though.

It could only be borne out of almost monk-like patience, incredible mental strength, razor sharp focus and an indelible belief in one’s ability to overcome adversity. From a purely mental perspective, this was right out of the ‘Geoffrey Boycott School of Batting’.