The commercialisation of cricket - a double-edged sword

Cricket, a quintessentially English sport that once stood to symbolise and inculcate 'Victorian qualities of gentility' during the imperial days, has now grown into a global multi-billion-dollar industry. So how did this quaint sport, once mostly played amongst Britain's elite class, become the world's second-largest sport in terms of fan-following?

The simple answer is commercialisation. Commercialisation drove the sport to first being televised and then being marketed. Television and broadcast, in turn, helped cricket reach more audiences than ever before. As cricket's popularity soared throughout the late 70s, more tournaments were organized, more teams wanted to join in and play the sport, and more people wanted to watch them.

Commercialisation also instigated a slow but perspicuous easternisation of the sport, both literally and symbolically. The centre of cricket is no longer England, and this became evident when the ICC moved its headquarters away from the Home of Cricket at Lord's eastwards to Dubai in 2005.

Cricket's popularity sky-rocketed in India post the 1983 World Cup. It was the perfect fairytale that captured the imagination of an entire nation. Next came the rise of one Sachin Tendulkar, which incidentally coincided with India's big television boom, and this led to cricket becoming the staple sport of the nation.

Nearly 703 million people tuned in to watch the 2019 Cricket World Cup, a 41% increase compared to the 2015 edition of the tournament, and for obvious reasons, Indian fans made up a major chunk of those figures. As cricket's popularity and audience grew in the subcontinent, the money followed. Then came the IPL - Lalit Modi's brainchild that soon became BCCI's most prized cash cow.

Cricket and business in the modern era

Even though commercialisation might feel like a recent phenomenon, it can be argued that the first time cricket met business was way back in 1977 during Kerry Packer's World Series Cricket. Packer, an Australian media tycoon, was the first real pioneer to recognize that cricket could be turned into a profitable business.

Brave and unafraid of experimenting, he wasn't bound by tradition or, for that matter, the laws of the sport. In fact, some of Packer's innovations like floodlights, coloured clothing, day-night cricket and most notably, the white ball, despite being considered sacrilegious at the time, are all widely used in modern-day cricket.

However, it's easy to understand why there's always an outcry from self-proclaimed purists every time something unconventional, such as The Hundred, is proposed. In fact, some purists shun tournaments like The Hundred and the IPL and go as far as labelling them as downright blasphemous to the sport itself. As they see it, cricket has already traversed into an undesirable path - a path that has seen the rise of limited-overs and franchise cricket at the expense of Test cricket.

Test cricket is considered the pinnacle of the sport itself, at least for now. As the ICC themselves claim on their website, "It is considered the pinnacle form because it tests teams over a longer period of time. Teams need to exhibit endurance, technique and temperament in different conditions to do well in this format".

In the eyes of a purist, limited-overs cricket fails to achieve this - it fails to test a cricketer's 'true' cricketing abilities and instead rewards them for being innovative and unconventional. It promotes 'quick thrills' and 'instant gratification' and turns cricket into a slogging contest that puts entertainment above all else.

This is when a purist's argument starts becoming reasonable. Limited-overs cricket, particularly T20 leagues around the globe (and The Hundred in extension), pose numerous threats to Test cricket. A philosophical concern, as Andrew Edgar writes in his paper, is that "in a consumerist society, Test cricket offers a perhaps nostalgic glimpse of a world where the capacity for deferred gratification is still to be valued" while T20 cricket prompts the erosion of this discipline.

Moreover, young and upcoming cricketers are increasingly mesmerised by globe-trotting cricket mercenaries who earn millions in the span of just weeks by offering their services to different franchises around the world. They are, however, not to be blamed for their fascination with franchise cricket - considering that the alternative involves playing Test cricket for their nation over long seasons while reaping financial returns that are a lot more modest in comparison.

It is no secret that T20 and franchise cricket fill up a cricket board's coffers a lot quicker than Test cricket does. Additionally, as multiple high-tier T20 leagues have cropped up worldwide, international calendars have increasingly become packed, and Test cricket has often been the format to fall under the axe. In blunter terms, cricket boards prefer to conduct T20 leagues at the expense of playing more Test cricket.

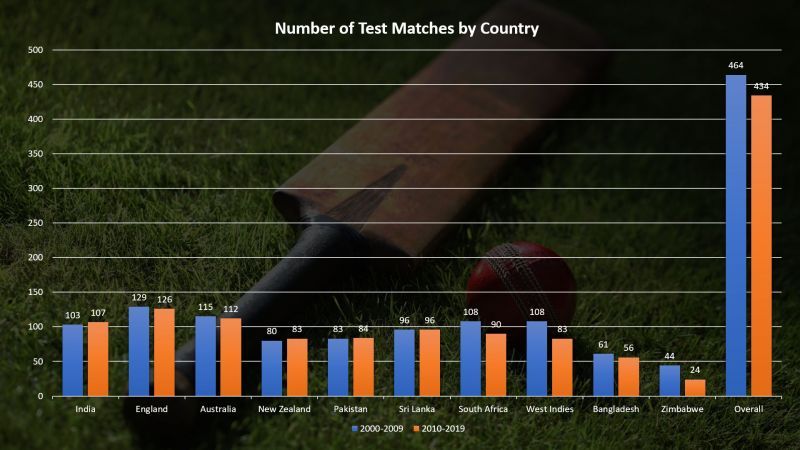

While the picture might not be so clear among what are known as the 'Big Three' cricketing nations - India, Australia and England - the difference is seen a lot more clearly in nations like South Africa and the West Indies, who've played far fewer Test matches in this decade than in the previous one.

As Graeme Smith, the former South Africa skipper, lamented, it is a vicious cycle. The fewer the Test matches that cricketers from these so-called 'lesser' cricketing nations play, the more they feel compelled to look for opportunities to play in T20 leagues around the world.

IPL - the biggest culprit?

Even if there is a case to be made for limited-overs cricket, what is the need for a region-based franchise league like the IPL when an even bigger one exists in the form of the Syed Mushtaq Ali Trophy - a tournament that features more teams, more games and more players?

The truth lies in the fact that tournaments like the IPL weren't born out of a need for another cricket tournament, they were born out of uniquely identified business opportunities that were waiting to be tapped into. It's important to understand that the IPL and the tournaments that have since followed its path aren't cricket tournaments that happen to sustain businesses - they are businesses that happen to feature a cricket tournament.

The IPL is so successful not only because it features high-quality cricket but also because it's a carefully curated business. Yes, the matches themselves are highly entertaining to watch, but they aren't the sole reason for the tournament's success. One of the key factors that set the IPL apart from other domestic tournaments like the Syed Mushtaq Ali, for instance, is the relationship it shares with its teams. `

The relationship between the IPL and its franchises is like the relationship between a flower and its petals. In other words, it's a perfect symbiosis. The IPL is like the flower's core, providing the franchises with the structure and support they require. The franchises are like the flower's petals, and in return, they give the IPL glamour and desirability.

It wouldn't be too far-fetched to postulate that only half of the IPL is played out on the 22 yards, while the other half is played behind closed doors in board meetings at luxury hotels. To put it in simpler terms, cricket is only the means through which franchises conduct their business. This does not sound as dubious after you realise that more than 70% of an IPL franchise's revenue comes from some form of advertising. Ticket sales and prize money make up but a small chunk of a much bigger pie.

At the end of the day, IPL franchises are brands. They are brands that seek to improve their visibility and, ultimately, their brand value. To put things into context, IPL franchises go as far as purchasing certain cricketers not to play cricket but to further their brand objectives.

Take Chris Gayle, for instance, who almost went unsold in the 2018 IPL Auction before KXIP (now Punjab Kings) swooped in to buy him at his base price in the third and final round of bidding. It was widely perceived that Gayle was purchased more so for his 'entertainment' abilities rather than his cricketing ones. One look at KXIP's team composition that year revealed that there was no real place for him in the starting XI. The fact that Gayle went on to play many match-winning knocks for them later on is a different matter altogether.

Franchise cricket - a threat to international cricket

A much larger concern, though with the rising popularity of franchise cricket, is that it poses a threat not just to Test cricket but also to international cricket as a whole. Former Proteas skipper Faf du Plessis minced no words while saying that T20 leagues around the world posed a serious threat to international cricket. He had the following to say in June 2021:

"T20 leagues are a threat for international cricket. The power of the leagues are growing year by year and obviously, in the beginning, there might be just 2 leagues around the world and now it's becoming 4, 5, 6, 7 leagues in a year. The leagues are just getting stronger."

If precedent is anything to go by, then Du Plessis may be right. The world's largest sport (in terms of popularity) - football - has gone down a similar path wherein international games are played in small windows that are sandwiched between multiple franchise leagues.

Du Plessis even went on to cite the example of numerous players from the West Indies electing to ply their trade for franchises around the world over playing international cricket for their nation.

And as we see money being pumped into franchise-based tournaments (like The Hundred) by the boards themselves, one can't help but worry that it'll continue to undermine local domestic circuits that have been around for decades. The problem here is that, as we've seen, no team can succeed consistently in international cricket without having a robust domestic system. As evidenced clearly by the conditions teams like the West Indies and Sri Lanka currently find themselves in.

The other edge of the sword

There is, however, a silver lining to what otherwise looks like a gloomy picture. The sport itself and those who play it benefit massively from both the shorter formats and franchise cricket. It can be argued that T20 cricket is the phenomenon that has pumped more money into the sport than anything else.

This, invariably, has first led to better financial compensation for cricketers across different levels, and it's also enabled cricket boards to invest more into development programmes.

Leagues like the IPL have made cricketers richer than ever before, and they've played a huge part in cricketers attaining fame and stardom (whether it's for the better or worse is another debate altogether).

Most importantly, though, as the IPL's slogan 'Where talent meets opportunity' suggests, it has indiscriminately provided cricketers - both young and old, both Indian and international - with an excellent opportunity to showcase their skills. Cricketers like Hardik Pandya and Jasprit Bumrah have the IPL to thank for being the catalyst that's helped them kickstart their international careers.

What's more heartening to see is that the model has trickled down to lower cricketing circles, leading to the formation of intra-state franchise leagues like the TNPL (Tamil Nadu Premier League), for example. Such competitions not only amplify all the benefits the IPL offers, but they also serve as sizeable stages, ones that are fairly popular, well-followed and televised, for young and local cricketers to showcase their skills on.

In addition, they've also helped put money into the pockets of financially ailing cricketers, giving them an opportunity to pursue the game full-time. Further, this allows semi-professional players to support themselves by just playing the game as opposed to having to look for odd jobs, in addition to playing, just to sustain a living.

The Hundred, too, despite being the oddball that every purist loves to hate, has done the game a great service. The women's game, which has been under relative obscurity until recently, has received a much-needed boost thanks to the ECB's latest money pit.

The Hundred put the women's game back on free-to-air television in the UK while the tournament's extensive marketing placed the women's game on the same map as the men's. To state it simply, the women's game has plausibly been the greatest beneficiary of The Hundred.

It's important to realise, too, that T20 cricket is a staple for associate nations. As a matter of fact, it's a staple for anybody who's looking to take up the game. T20 cricket is a much more digestible offering of the sport. It gives new audiences and players a small yet nearly complete dose of what cricket the sport has to offer.

Regardless of what critics might say, there is still hope for Test cricket too. People still flock to grounds by the tens of thousands to watch Test cricket in countries like England and Australia.

The ICC's initiatives to first promote day-night Test cricket and then to conduct the World Test Championship has only helped the cause. Most importantly, though, the dream of most young cricketers remains to represent their nation in whites - at least for now. Test cricket might well be past its glory days, but its flame still burns bright.

Thoughts for the future

The hope is this - in what I would see as a utopian future - Test cricket will still remain as the most elite format, and while not being at the pinnacle in terms of viewership figures, it'll still retain its prestige as being the purest representation of the sport itself. Franchise cricket will play its part in capturing audiences and will help grow and increase the reach of other forms of cricket, including international cricket.

It is, of course, impossible to predict what the future holds for this game that we all love so dearly. At the end of the day, commercialisation of the sport is a double-edged sword in every sense; it's boosted the popularity of the game and brought more money into the sport than ever before - but at the same time, it has contributed to the erosion of some of the game's most prized values, values that have been deeply rooted in the sport for centuries.

At the end of the day, one can only hope that this metaphorical sword slays more foes than friends. In that sense, commercialisation is truly the blade that cuts both ways, isn't it?