The Day Sabina Was Silenced: Steve Harmison's 7/12

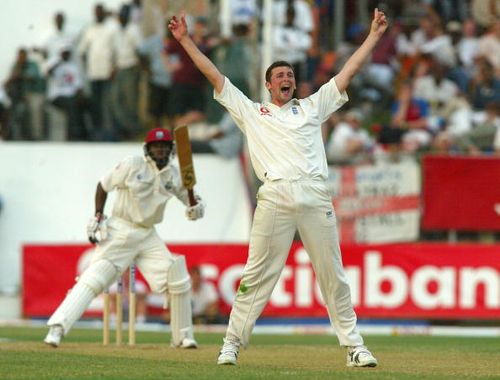

Steve Harmison of England takes the wicket of Tino Best of the West Indies during the Cable and Wireless 1st Test match between West Indies and England at the Sabina Park Cricket Ground, on March 11 2004, in Kingston, Jamaica.

At his best, few fast bowlers could be as devastating as Stephen Harmison. His withering pace and the steep bounce he generated made him as likely as any bowler who ever played to overawe a line of good batsmen. But he was not always at his best. He frequently appeared listless and his radar was often awry; instead of being the match-winner that he could be, he was often the source of frustration for his team and captain.

Renowned as a troublesome traveller, he was the subject of endless conversations in cricket circles: would he overcome the fragility that plagued him and grow into one of the best fast bowlers of his time, or would he remain one of cricket’s great unfulfilled talents? By the time England’s 2003/04 tour of West Indies came round, he had showed his true capabilities only sporadically, with his most notable performance being his 4/33 upon returning for the last Test against South Africa in September 2003 at the AMP Oval, Kennington. Later, his nine wickets against Bangladesh in Dhaka earned him the Man of the Match award, before a back injury laid him low for the rest of that series and for the following encounter with Sri Lanka. Fortunately for England, he regained full fitness in time for the West Indies tour.

I first set eyes on the tall pacer when I watched a day – I don’t remember which – of the tour match against Jamaica. The track seemed lifeless. Hardly a delivery rose over stump height and I remember thinking that if the Test match pitch was similar in nature then the batsmen would not be overly troubled. But then Harmison came on and it seemed a totally different surface. Suddenly, batsmen who were playing deliveries just short of a good length comfortably around stump height, found that they now had to be protecting their ribcage. The 6’5” bowler never took a wicket in the game, but I came away thinking he would be the bowler to watch when the real battle began in a few days.

Only 28 runs separated the teams on first innings of the Test. Opener Devon Smith’s 108 had led the West Indies to 311, and England responded with 339. Chris Gayle and Smith then survived three overs to close the third day with the West Indies on eight and the match intriguingly poised entering Sunday’s fourth day.

For some reason that I don’t now recall – and quite unusual for me – I was a few minutes late getting to the Park that morning. The loud roar while I stood at the turnstiles meant that a batsman had fallen. It was Gayle. He was Harmison’s first victim, caught behind flashing at a delivery he could have ignored. The crowd was disappointed that their Jamaican favourite had gone so early and so needlessly, but did not seem overly perturbed, having some faith in those to follow. Before I was properly seated, however, another wicket fell, Sarwan this time, LBW to Harmison, and by the time Chanderpaul diverted the gangly pacer onto his stumps, the floodgates had truly been blasted open. The West Indies’ then stood at 15/3.

Next it was Lara’s turn, and it was then clear that total capitulation was a real possibility. Surely, one of the greatest batsmen the game had known could beat back the rampaging pacemen and prevent a complete overrun. He had done it before. His 213 on the same ground in 2001 stopped the advance of the marauding Australians and, in company with Jimmy Adams, erected a platform from which Courtney Walsh and Nehemiah Perry wrought an unlikely victory. The West Indian captain was accompanied to the middle by the riffs of Caribbean cricket anthem “Rally round the West Indies” and the stunned crowd was hopeful.

That hope crashed after exactly five deliveries. Matthew Hoggard ran one across the left-hander and had him caught behind.

Meanwhile, the vicissitudes of capitalism was on full display in the stands. Vendors who came amply stocked with supplies expecting – understandably since the game was just half way through – a full day, realized before long that the impending early end would leave them stuck with most of what they had brought, much of it perishable. The result was that prices were tumbling in sync with the West Indian wickets – each wicket had an accompanying price drop.

Spectators too had to make adjustments to accommodate the looming early finish. Many who had come armed with strong liquid refreshments to enliven the proceedings could be seen sharing with their fellow mourners, both as a means of treating dejection, and also to lighten the load they would need to take back home.

All this time, wickets were still going down. First innings centurion Devon Smith was caught and bowled by Matthew Hoggard, who himself was well into a challenging spell.

A snorter from Harmison took care of Ridley Jacobs. Leaping at him from just short of a length, he could do no more than glove it. Nasser Hussain, fielding at short leg, ran to his left and accepted the catch behind the wicket. In the circumstances, it could probably be said that the 15 he scored was a reasonably good innings, especially since it turned out to be top score.

Steve Harmison of England with his Man of the Match award during Day Four of the First Test between West Indies and England at Sabina Park on March 14, 2004

Another screamer would have separated Tino Best from his head had he not removed it from the delivery’s path. But his instinctive jab left his bat in the way for the ball to touch on its way to the keeper. Adam Sanford was then caught by Marcus Trescothick, the first of the six – yes six – slip fielders that were lined up alongside the wicketkeeper. Trescothick was the catcher again to end the massacre when Harmison took Fidel Edwards’ edge for his seventh wicket.

The West Indies innings had collapsed in a heap for 47 and Harmison’s 7 for 12 was the cheapest seven-wicket haul in history. Five batsmen failed to score; only two reached double figures, and all the doubters were convinced, for the moment at least, that Harmison was now the fast bowling force they all thought he could become.

And for a while he was. The New Zealanders tasted his fire soon afterwards with many batsmen feeling the agony of the ball smashing into ribcage or fingers pinned to bat handle. The gangly fast bowler was instrumental in England wresting the Ashes from Australia in 2005, and there was 6/19 and 5/57 against Pakistan at Old Trafford in 2006. But he was still unpredictable; sometimes he was downright horrid, and the match-winning performances became scarcer and scarcer.

His nadir was probably the first delivery of the 2006/07 Ashes series that was collected by Fred Flintoff standing at second slip. A delivery the English press dubbed the worst ball in test history, and a far cry from his incredible performance at Sabina Park, one his then captain called “one of the best spells by an England bowler.”