The finest Indian pace trio? Not Quite

Aaron Finch, right-hand-bat, takes his guard at the MCG. Ishant Sharma, right-arm medium pace, will open the attack from around the wicket. Sharma steams in, wrist pointing first slip, bends his back, and shows his all to a homed-in Finch.

The first ball is a corker. He lures the batsman into the cover drive in exactly the last nanosecond, the ball pitches, zips and trills and swings past the inside edge. A barrage of ‘oohs' and ‘aahs' deluge Finchy’s ears. Ishant has his head in his hands.

Twice on this tour has Ishant Sharma gotten the better of Austalia’s premier opener. But this time it wasn’t him – it was an 8-matches old rookie Indian pacer that conjured up a snorter that had Finch’s name written all over it.

Jasprit Bumrah would eventually go on to record a career-best 9-86, and his partner in crime would scalp six wickets lesser than him. But if you’re in this Indian team, that figure matters the least. As Bumrah himself reiterated at the post-match presentation, someday you get wickets, someday your mate does. And oh boy, isn’t that attitude paying off?! You bet.

The Indians are on cloud nine. But wait, there’s an asterisk. Fast forward to July, please.

*****

The Indians are well and truly bossing the match here at Edgbaston. 87-7 does the scoreboard read, all of England’s hopes resting with a certain Sam Curran, the archetypal English all-rounder who does a bit of this and a bit of that. Here’s a chance to skittle these peeves out for a paltry score...

But aye, this lad doesn’t seem to get out. There’s ‘intent’ in his strokes, there’s technique in his defence. The finest Indian bowling line-up, as described by the likes of Michael Clarke, is unable to run over a 20-year-old kiddo, who is wreaking havoc over their spirits, much to the evanescent mirth of this jovial English crowd. England finish with 180 on the board, Sam Curran 63 off 65.

Ageas Bowl, August 3. It’s Déjà vu everywhere. England make their way to 246 from 86-6 on the back of another colossal partnership for the seventh wicket, and it’s that prick again. Sam Curran top-scores with 78 and Moeen Ali chips in with a gritty 40, as Indian shoulders slumped again, Indian hearts burst again. The Barmy Army sings.

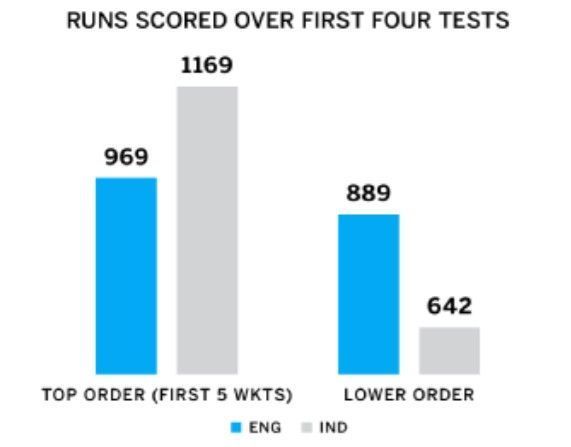

Nothing recapitulates this Indian bowling attack as much as these three instances. Right from the onset of their overseas endeavour, they have been fabulous bowling to top orders, but due to some weird, wacky reason of their own, missing the trick against tailenders. And even at the MCG, it was misses-it-between-the-cup-and-the-lip for India.

When Pat Cummins shook hands with Nathan Lyon at the end of the day’s play at the MCG, India’s eyes were not the picture of confidence and panache that they usually seem to be. There was fear of the unimaginable, apprehension of the uncontrollable, and frustration following retrospection.

What this calls for, needless to say, is an astute factorization of India’s infrequent blushes on the lush green overseas outfield, after the pedigree batters are back in the Hut, as the least skilled willow-wielders enter it.

Dichotomy South Africa, dichotomy England, dichotomy Australia. Of the 6 openers that India have encountered in 2018 (Dean Elgar, Aiden Markram, Alastair Cook, Keaton Jennings, Aaron Finch, and Marcus Harris), with the possible exception of Cook’s last supper at London, only Dean Elgar has played a single knock of note, his workman-ish 86(240) at Jo’burg.

And, if you talk about South Africa’s and Australia’s No. 3’s, Hashim Amla and Usman Khawaja, there’s only one knock that stands apart – Amla’s 61(121) at the same venue (Both these knocks came in a losing cause). Joe Root himself accounted for only 13% of England’s runs, in all five games combined.

This suggests that the three top-order batsmen in all three overseas tours have more often than not, been walking wickets. Alastair Cook was terribly out of form, Finch and Jennings have been two breathless fishes out of their aquarium, Harris hasn’t seemed to belong in the highest level of cricket. So maybe, as much as we attribute these incredible statistics to India’s bowlers' supreme skills, there is also a demand for an appropriate understanding of the malaise of all three top orders.

Jack Welch once said, that ‘If the rate of change on the outside is greater than the rate if change on the inside, the end is near.’ Modern-day cricketing nations, probably with the advent of T20, have recognized the importance of an able lower order that juxtaposes aggression with composure and restrains their instinct go for a booming lofted shot at the sight of a juicy half-volley.

India’s tour of England gave a glimpse into the English lower order which featured Moeen Ali, who started his career as an opening batsman for England, at No. 8, followed by India’s wrecker-in-chief Sam Curran at No. 9. The quality of England’s lower order is accentuated by the fact that the ninth wicket averages 36.71 – a figure bettered by only their 3rd and 5th wicket partnerships. Stuart Broad, with his un-broad batting credentials, was part of three 50+ stands.

Contrast that to India’s lower order that boasts of the tonking abilities of Mohammad Shami at No. 8, Ishant Sharma’s anachronistic tuk-tuk at No. 9, Umesh Yadav’s shut-eye-slog-ball impeccable strategy at No. 10, and Jasprit Bumrah at No. 11, who would make a no. 11 even if you made a team out if all the batsmen who bat at that position. In case you were on a Christmas holiday and couldn’t catch the match, believe me – that was the lower order India fielded at Perth!

If there is a certain complacency that is littered in Indian bowling arms at the sight of burly, gutsy tailenders taking the field, it perhaps stems out of this very choice – this very choice of opting for bowlers who can’t bat, to fill the lower order.

This choice reveals a lack of recognition of the enormous amount of change that has swept the world over the past year, and inevitably, to the belief that the opposition resembles you – which, as we saw at Edgbaston, Ageas Bowl, even against the Windies, and the MCG, is self-defamatory.

It is responsible for a culture that debauches intensity, and robs one of ruthlessness – for the buzzword that it was before India departed for South Africa.

Virat Kohli hasn’t got just two chromosomes per cell. He has more. Enough has been said about Kohli and managing his inhuman workload. But so little for the bowlers who run in at 25 kms an hour, lift up the dumbbells for strength training, and take painful blows to their shoulders with every revolution of the arm that produces a 140 clicks jaffa. The numbers speak for themselves.

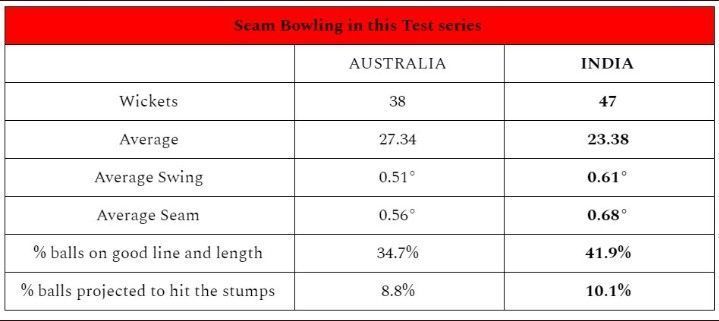

According to CricViz, Bumrah has produced an edge or a miss of an Aussie batter every four deliveries. For bowlers who have delivered as many balls as him, that is the fifth best stat of all-time. Indian seamers end 2018 with 179 wickets. They've never taken more in a calendar year. Using the same limit in terms of balls bowled, Bumrah's effort is the best performance for a Test series outside of England.

This round-the-clock-slogging has certainly been no soothing music to their ear; if the wear and tear is having a bearing on India’s apparent smugness, it needs to be addressed sooner than later. Because this is a historic attack. And India needs to keep it fit.

Resting one if the quicks for the Sydney Test, in place of a spinner, and slotting in Pandya for Rohit Sharma is worth giving a thought. Pandya’s presence, not only adds stability to the lower order but also makes room for a second spinner, because the SCG, for ages, has been the most Indian of Australia’s cricket grounds.

Harsha Bhogle, the Voice of Indian Cricket, tweets post India’s triumph at the MCG: ‘2018 has been an unbelievable year for Indian pace bowling. I didn't think I would say that when I started covering cricket.’ And one cannot help but nod your head in agreement, bow down to this Indian quartet in a coalescence of reverence and adulation.

It is all worth the hyperbole, and they’re still probably the best in the world, despite all the whines over rolling over the lower-order. The day this attack crushes their ostensible Achilles Heel called the tail, then boy, it’s safe to assume we have with us not just the finest Indian pace quartet, but also one of the finest seam bowling line-ups, ever.