The importance of running between the wickets while chasing in the modern game

If we can best describe India's win over Australia in the third ODI, and consequently the series, it would be with a movie and a famous dialogue from another.

Run, Forrest! Run

"Do do do" ( translation: Two two two!) was the call. It was another drive placed between long-off and deep extra cover after which Dhoni hared across. This would happen for another six times in the innings: across various parts of the ground: to midwicket, long-off, a leading edge which would fall short of fine leg. Then came "teen teen" (translation: Three three!). There would be five of them, again across various parts of the ground. 34 singles; 3 of them stolen. This looks like a charge sheet! The crime being 11 stolen runs, by Dhoni.

A similar charge sheet was filed on Jadhav as well, who had stolen at least 10 runs. It might sound overly dramatic but with an ODI series win on the line and a last-over finish deciding the match, this is where the match was won by Team India.

Catch me if you can

Catches win matches. Definitely, being sharp in the field is a key asset for any side, but that alone wouldn't (anymore) win it. Who wouldn't remember Khawaja's gravity-defying catch to dismiss Virat Kohli in the first innings of the Adelaide Test? In the last ball of Day 1 of the same Test, in fact, in the same innings, a brilliant run-out by Pat Cummins dismissed Cheteshwar Pujara. Two of Team India's best batsmen, dismissed by two acts of brilliance on the field, in the same innings, on the same day! Australia went on to lose the match by 31 runs. Of course, comparing a Test match to an ODI, where the scope of recovery from an error is considerably less and the game runs out of the hands of a team in a matter of overs, rather than a matter of sessions, is not fair to the overall case being made here.

The point, however, is that the inability to stop India pinching tight singles and converting ones to twos and twos to threes was as crucial as Maxwell's drop of Dhoni when the latter was yet to score his first run.

Where it all began

Cricket has come a long way from a point where bowling or batting excellence was able to win matches for teams. It still is the basis over which strategies are made, but that is definitely not the difference anymore. Match awareness, intensity, fitness, whatever may be the parameter, it is definitely subtle things between the lines which decide matches.

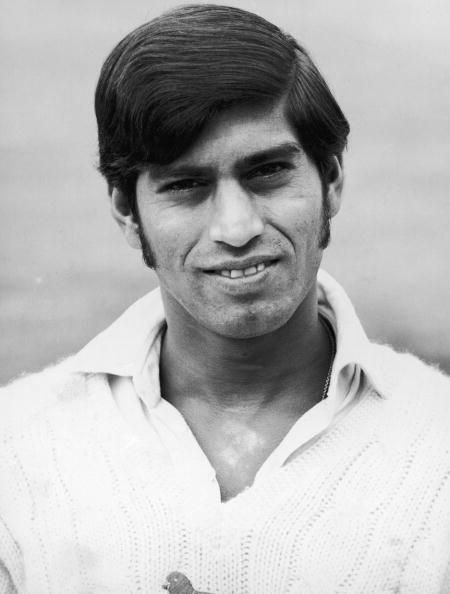

One such aspect which was considered a thin line between batting and bowling was the ability to save runs on the field: fielding skills. The first Indian player (as far as my knowledge in the game goes) to have retained his place in the side for his expertise in fielding was Eknath Solkar. Solkar is classified as an all-rounder but is more famous for his ability to have very quick reflexes, be it at FSL or at point. A strike bowler or a stroke-maker who would contribute little in terms of runs saved for the team was passable back in the '70s and '80 even up until the late 2000s. That makes Eknath Solkar's contribution all the more special, as it was difficult in his days to recognize his contribution to the team.

The all-conquering Australians were once again the early trendsetters (if not pioneers) of fielding a team where the majority were excellent athletes as well. Symonds, Bevan, Ponting, Clarke, Hussey (both Michael and David) and Lehmann were a notable few who were excellent on the field apart from their obvious talents with the bat or ball (or both).

After fielding was no longer considered a luxury but a necessary skill for a player, awareness of the situation and ability to take teams over the line has emerged as a luxury for a team. One particular batsman devised a unique method of chasing down targets, which did not involve mighty swings of the bat at the death overs, and a prayer. It was a calculated and methodical breaking down of the target mixed with well-planned bursts of aggression in between, choking the opposition all the while. More of a python slowly congesting its prey. The doosra of chasing. Michael Bevan, for the uninitiated.

Known as the finisher for chasing down targets very successfully, his modus operandi was very similar to what MSD has championed: milk the good balls for one and twos, convert the ones to twos and twos to threes and definitely punish the bad balls. He was so skilled in pinching singles and doubles that he only scored 28% of his ODI runs in boundaries. Out of the 9320 balls he has faced, only 471 were dispatched to the boundary. This extraordinary work rate made him stand out in a team brimming with great individual talents and who was single-handedly capable of winning matches for their teams. This skill of planning and perfect execution kept the scoreboard constantly ticking and ensured no pressure was built by the bowlers on his team.

This method requires meticulous planning on part of the batsman; select bowlers whom he is planning to attack and execute this to perfection. On top of that, in order for this ploy to work, it requires an indomitable ability to soak in pressure and still not lose sight of your plans. In fact, this is what has made Jadhav's knock all the more impressive. MSD remaining calm in a tense chase is a sight common for Indian cricket fans (our nerves are made of ice and steel, you see!). To see Jadhav maintain a cool head and not panic was a sight to behold. Seeing him blossom as a potential finisher is very satisfying.

What to expect?

Bowling teams would definitely identify methods to minimize this dangerous (almost epidemic!) habit of trying to pinch runs under the noses of fielders. It is definitely this skill of successfully pulling off a "planned assault" in a run chase which is highly sought after in today's limited overs game. Ultimately, these thin lines which are deciding games would be identified and attempts would be made to ensure these lines get thinner, but any batsman with a knack of such finishes always find these lines, no matter how fine they appear.