The metamorphosis of James Anderson from ‘Daisy’ to swing-king

During a typical rain-sodden English summer season in 2002, James Anderson lit up the Old Trafford stadium with a booming in-swinger that trapped Surrey’s run machine Mark Ramprakash dead in front. In his first county game itself against Surrey, the shy lad from Burnley, left Lancashire’s cricket cognoscenti spellbound with a vivacious spell of swing bowling.

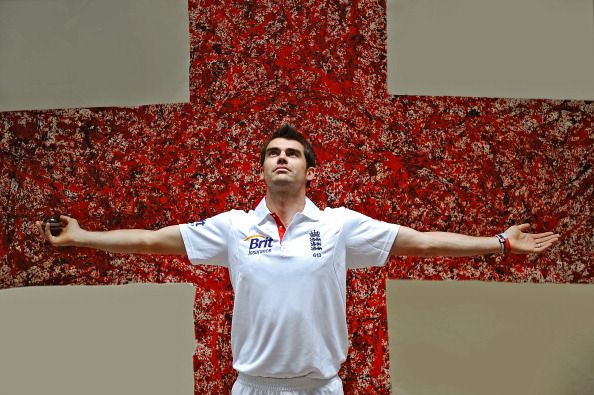

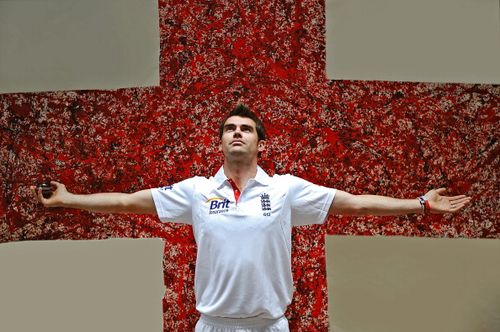

Fast forward to our present time. The shy lad, James Anderson, has become a nasty swing bowler who snarls, growls and even sledges at the batsmen. The banana-bending swing bowler from Burnley is a fine manipulator of the ball. With subtle changes of wrists and fingers, he orchestrates unsuspecting batsmen’s downfall by exploring every nook and cranny in their defence. Anderson’s adroitness with a red cherry in hand is unquestionable. In short, at the age of 30, James Anderson is the irresistible force of English cricket.

If we turn back the years and trace Anderson’s early career, it feels like listening to a fairy tale story. Lancashire’s the then player-development manager John Stanworth was impressed by Anderson’s range of skills and tried to persuade Lancashire’s coaching staff to have a look at him. Incidentally, Lancashire, just like other counties, wanted to hire an overseas professional. But Anderson’s range of skills impressed the coaching staff, and he was drafted into the side.

In his first season, the Burnley Bullet regularly scythed through county batting line-ups with pace, cut and swing, and gave batsmen all over England headaches. Those 50 wickets he took in 2002, caught the eye of England’s swashbuckling opening batsman Marcus Trescothick. When England’s touring party to Ashes in 2002/03 was ravaged by injuries to key fast bowlers, Trescothick recommended Anderson’s name to England’s captain Nasser Hussain. Anderson subsequently made his debut at MCG, in a one-day match against Australia.

Anderson’s fairy tale story continued, as he ripped through Pakistan’s explosive batting line-up in the World Cup at Cape Town in 2003. For most fast bowlers, bowling an out-swinging yorker on off-stump is beyond the realms of possibility, but by sending Yousuf Youhana’s (now Mohammad Yousuf) off-stump somersaulting with the new ball, Anderson made it a reality.

The hat-trick Anderson took against Essex in a county match in May 2003 helped him to break into the Test side as well. In his first Test at the hallowed Lord’s cricket ground against Zimbabwe, he swerved the ball away from right-handers and took a 5-for. He was suddenly the talk of the town and was even touted as the saviour of English cricket.

Unfortunately for Anderson, his honeymoon period was soon coming to a very bitter end. The coaching staff started to tinker with his action and the emergence of the troika of quick bowlers: Flintoff, Harmison and Simon Jones led to Anderson just warming the benches.

Whenever James Anderson got a rare opportunity to play, he bowled like a loose cannon. No one could blame Anderson for such capriciousness, as he was made to play Tests without many games under his belt. When Anderson replaced Simon Jones for the Wanderers Test during the tour to South Africa in ’04/05, he hadn’t played even a single first class game for close to five months. It is hard to fathom why the coaching staff didn’t think of playing him in the first class game against South Africa A at Potchefstroom. It shouldn’t surprise anyone that just like hungry vultures, South Africans tore Anderson’s bowling into pieces.

Anderson remained on the periphery of the English XI. He wasn’t selected to play in the XI in Ashes 2005. It must have been a bitter pill for him to swallow, as England went onto win a historic Test series against Australia. Every English cricketer’s dream is to play in the Ashes, but in ’05 that dream didn’t materialise into reality for Anderson.

When called up as a replacement for the injury prone Simon Jones during the tour of India in ’05/06, he did make his presence felt by taking six wickets at Mumbai. But with Anderson, every good show was juxtaposed by a poor performance. It made the critics give him the nickname ‘Daisy’.

Another body blow to Anderson’s career came in the form of a stress fracture he suffered on his back in 2006. The worst part of it being the fact that the injury was caused due to coaching staff constantly tinkering with his action. These days, young bowlers are indoctrinated to bowl with a certain action, leading to loss of form and even injuries. When Anderson was bowling with his natural action, he was hooping it around corners and taking wickets. But that wasn’t the case with his remodelled action.

The timely advice by former Lancashire’s coach Mike Watkinson, to go back to his old action, helped him to find his swing back. But on the cricket field, his career touched its nadir as the Australian batsmen took a liking to his bowling. In the Ashes ’06/07, Anderson took just 5 wickets at an average of 82.60. To make matters worse for him, he had bowled a mere 34.1 overs since his comeback from the back injury. Yet, the English selectors and coach Duncan Fletcher were convinced that he will be match fit to take on the blood-thirsty Australians, waiting to take revenge for the ’05 Ashes loss. It was certainly a tumultuous year for Anderson.

With injuries to Hoggard, Harmison and Flintoff in ’07, Anderson got a window of opportunity to show his wares against the touring Indians. He made that chance count, by taking a 5-for at Lord’s. Anderson seemed to be in a relaxed state of mind, and by going back to his original action, he was able to generate prodigious swing. Anderson also seemed to have worked very hard on his in-swinger, as he bowled the in-swinger with better control, and troubled the Indian batsmen throughout the series.

The watershed moment in Anderson’s career came about in ’07/08 in New Zealand. England’s coach Peter Moores decided to drop both Hoggard and Harmison. England had lost the first Test at Hamilton and as a result, Moores wanted to inject fresh blood into the pace attack. Broad and Anderson were selected for the game at Basin Reserve and England won that Test convincingly. Anderson in particular had a good game as he took a 5-for at Basin Reserve.

James Anderson caused more misery for the Kiwi batsmen when they toured the Old Blighty in ’08. At Trent Bridge, he put on a virtuoso exhibition of swing bowling to make short work of New Zealand’s batting line-up. The way he slanted the Duke ball into the Kiwis, before making it to swing away late from right-handed batsmen to uproot the stumps of both Redmond and McCullum was a sight to behold. Late swing has become one of those utterly mundane cliches used by commentators to describe every swing bowler going around, but it sits well with Jimmy Anderson.

When Pakistan toured England in ’10, Anderson ran riot by bowling on some sprightly tracks. He took 23 wickets in that series at an average of just 13.73. The peach of a delivery he bowled to send Farhat’s stumps cartwheeling at Trent Bridge was a swing bowler’s equivalent to Shane Warne’s magic ball in Ashes ’92. By bowling from around the wicket, he swung it into the left-handed Farhat, before it virtually snaked away at a high speed to take out the off-stump. Farhat must have felt like he had been hit by a 440-volt shock that day.

In spite of some sterling performances for England that year, there were lingering doubts about Anderson’s ability to perform on hard wickets and with a kookaburra ball Down Under. It seemed to have spurred Anderson, as by banishing all his inner demons, he bowled with zest, verve and gusto to take 24 wickets in the Ashes 2010/11. It was a spirited riposte to all those critics baying for his blood.

He didn’t have sheer pace to send the Australian batsmen quivering for cover on those hard wickets. But Anderson used every little trick available to a swing bowler to succeed. If it was swing that got him those prized scalps of Clarke and Ponting at Adelaide, then with seam movement, he impressed everyone at Brisbane and Melbourne. At SCG, he used reverse swing to good effect in the second innings. The now famous Anderson’s ‘knuckle ball’ and his surprise in-swinger kept the Australian batsmen on tenterhooks. To make it worse for the left-handers, he would bowl from around the wicket, and by using the crease, bait them like a temptress. Australian batsmen found it hard to decipher Anderson’s modus operandi in that series.

In Australia, Anderson seemingly had the ball on a string, and did whatever he wished to do. Cricket pundits compared him rightly to a cheetah, as just like a true predator, he was preying on unsuspecting batsmen stealthily. The way he would set up a batsman, before delivering the coup de grace was a sharp contrast to the Anderson who bowled with lingering self-doubts in ’06/07 Ashes.

In 2011, Anderson’s effervescent endeavours even helped England to usurp India as the number one ranked team in Test cricket. Last year, he hammered the final nail in the critics’ coffin by succeeding in Asia. He strained every sinew on abrasive surfaces of UAE, Sri Lanka and India and did well. In India, he continuously played on the batsmen’s minds with a mixture of in-dippers and swing. It tells us that a good bowler can succeed anywhere.

With 295 wickets to his name, Anderson is on the cusp of becoming only the fourth English bowler to take 300 Test wickets. In the ongoing series in New Zealand, he has been slightly below par. But it shouldn’t take long for Anderson’s competitive juices to flow again.

Just having a glance at Anderson’s bowling average of 30.46, it can be misinterpreted that he is overrated. But he was mismanaged by the coaching staff, and as a result, took more time to mature. In his last 35 Tests, he has chalked up some impressive numbers, as he has taken 147 wickets at 26.03. It also has to be said that these days, bowlers have to bowl on some flat decks. With modern day batsmen sporting all those strange accoutrements, it makes that much harder for a bowler to make his mark. The metamorphosis of Anderson from being called a ‘Daisy’ to a world class swing bowler can be a ray of hope for all those promising quicks struggling to make their mark.