The secret sauce of India's Test success in the WTC

After defeat in the third Test against Australia in Indore, questions are being asked about the Indian top order post another sub-par batting performance.

While this is a natural reaction to a rare home defeat, curiously, it might be the first time in many years that the Indian batting unit is being criticized collectively without naming or shaming any particular individual.

India's top-order batting woes

Since the beginning of 2021, in 17 innings at home where India lost five or more wickets, India's first five wickets have contributed an average of 154 runs and have crossed 200 only five times.

The highest was 266 scored versus New Zealand at Kanpur in the first Test of the 2021 series, which is also the only draw at home in the last three years.

same period, with a cut-off of more than three matches, while batting in the top five, the averages of the key players read Rohit Sharma - 45.9, Virat Kohli - 25.0, Shubman Gill - 24.2, Cheteshwar Pujara - 23.3, and Ajinkya Rahane - 20. Only Mayank Agarwal, with an average of 43 has performed better than his career average.

Diving into more detail, India's Test batters have scored 16 Test centuries at home in the same number of matches at an average of one per match. That is a drop of more than 50 percent compared to an average of 2.2 from January 2014-July 2019 (World Test Championship (WTC) started in August 2019).

Across the same two periods, the team's batting average has dropped by broadly five runs from 42.8 to 38.2. Post-pandemic, it drops further to 30.7. Mathematically, on average, the Indian Test team since the beginning of 2021 has been scoring broadly 133 runs less at home vs. an average score of 2014 to 2019.

The drop is alarming, especially considering the sample period of three to five years is reasonably long to accommodate both the peak and trough.

Is the time ripe to change? Is India's top-order underperformance holding India's, arguably, the most well-rounded and skilled bowling attack from achieving greatness?

The answer is no. As a matter of fact, they might be playing a salient role in their success.

Not winning a home Test is no longer an option

Over the past couple of years, especially since their loss to England in the first Test in Chennai in 2021, the Indian Test team has focused on developing surfaces that suit their strengths and more importantly take the toss out of the game.

The general belief among the Indian team management is that if the ball turns from session one, it provides a fair chance for both the teams rather than a pitch that starts out assisting the batters and deteriorates as we reach Day 4 and Day 5.

For reference, barring England, over the last 20 years no team has managed to win more than a Test in India after losing the toss. Australia's recent win in Indore was their first triumph since 1998 after calling the wrong side of the coin. The strategy agrees with the demands of the WTC.

In the tennis analogy, winning a Test at home is equivalent to holding your serve, especially against tough opponents including England and Australia. While a defeat affects 100 percent of your points, even a draw results in a 61.5 percent loss of the full points.

It is quite a significant blow considering how difficult it is to gain any points in an away Test match. The fact that India, Australia, and England play nine to 10 Tests versus the other two teams in every WTC cycle makes every point even more significant and strenuous to achieve.

On the back of the spin trio of Ravichandran Ashwin, Ravindra Jadeja, and Axar Patel, India have won 83.3 percent of their points at home across two WTC cycles. Had the WTC existed from January 2014 to July 2019, India would have achieved total points of 81.2 percent at home, just 2pp less than their WTC score.

Hence, it may be argued that the improvement is marginal. However, when compared to other teams at home, they are currently approximately 5pp above second-best Australia, and a whooping 30pp more than the average of the top eight teams at home across 2 cycles. In short, numbers back the strategy.

India is no longer a batting paradise

Adopting and backing a strategy that brings better results seems pretty straightforward unless you are talking about Indian cricket.

The average Indian cricket fan is not rational. He/she wants to see their team win but cannot accept their superstars' failure. Strategies and processes are not part of daily cricket conversations. As such, it is extremely tough for the players.

Since India started playing Test cricket in 1932, India as a host country ranks third among aggregate batting averages, only behind Pakistan and UAE (technically Pakistan).

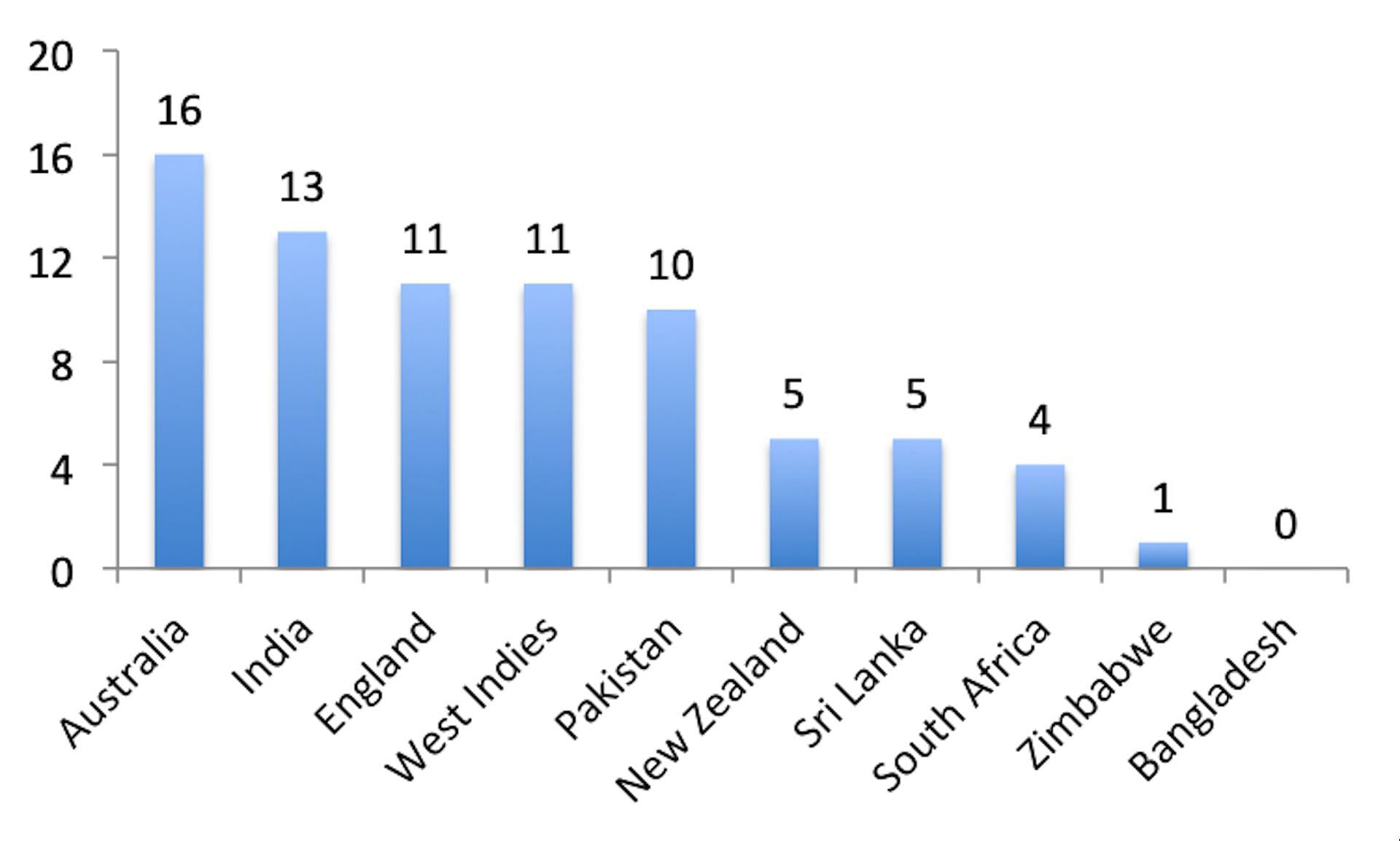

In terms of individual batting averages, India is ranked second with 13 batters averaging above 50 at home, only behind Australia with 16 (see below). This has, however, changed significantly in the last three years with only one batter averaging above 50 - Rishabh Pant.

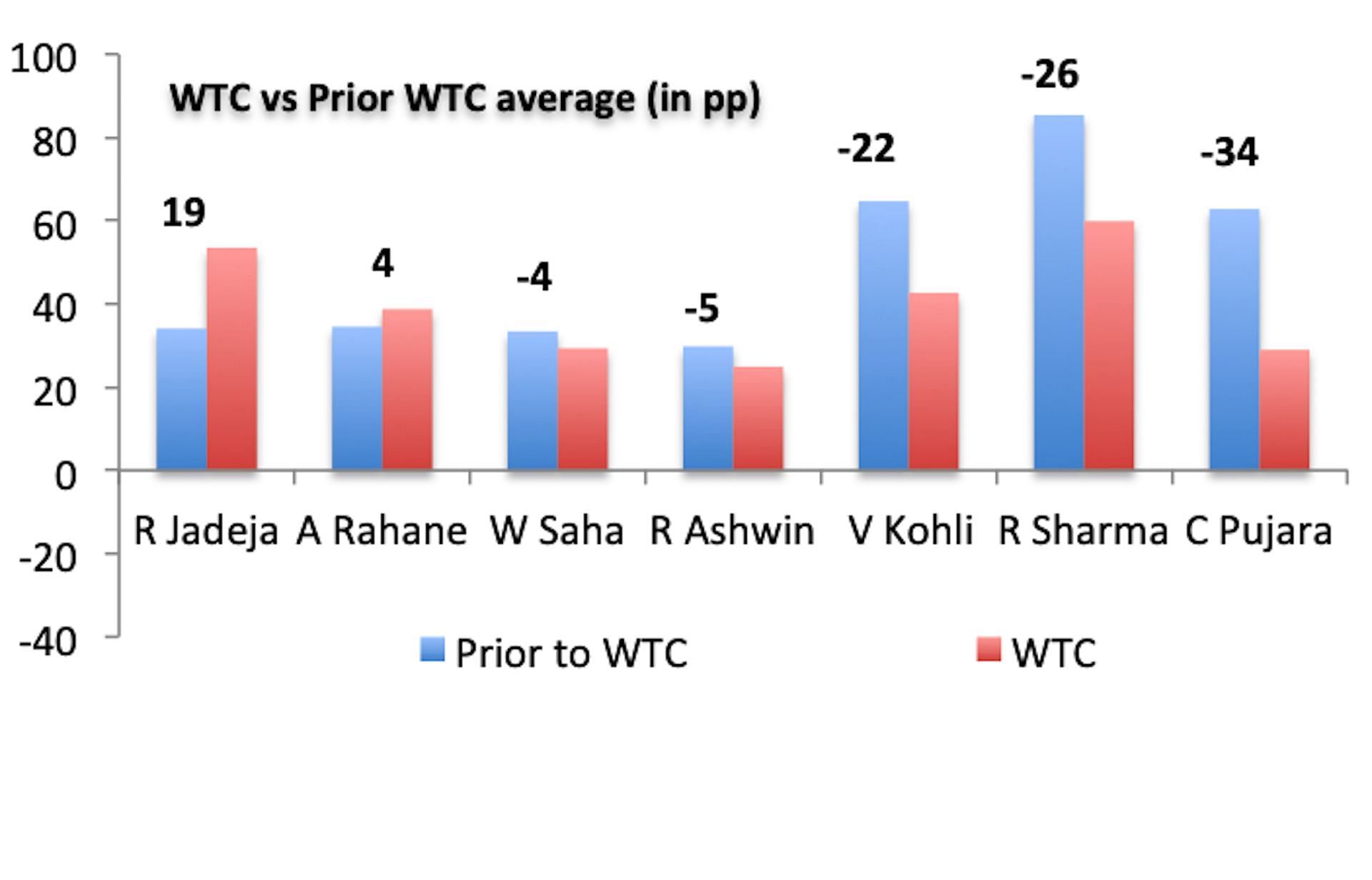

There has been a significant drop in batting averages for almost the entire team since the beginning of the WTC (see below).

As Jarrod Kimber mentioned in a video on his YouTube channel, it cannot be a fluke that almost the entire team has lost their form in recent times. The drop in average is certainly a result of a well-thought-out plan.

(Please note that we have excluded Rishabh Pant, Shreyas Iyer, and Mayank Agarwal from this analysis as they featured in less than five games before the WTC while KL Rahul has played just two matches at home in the WTC).

The selfless Indian top order is indeed the secret sauce

Every well-thought plan needs backing from its team. Currently, batting with a new SG ball on rank-turners has to be one of the most difficult gigs in Test cricket.

The only opportunity to score big runs is to hope that you have survived till the ball goes soft and then capitalize. This is precisely why India's lower order has performed way better than its top order. A case in point would be Ravindra Jadeja, who scores significantly higher if he bats after 50 overs of the innings versus earlier.

This is a big shift from the 90s and 2000s when teams scoring 400s and 500s were a regular feature. Even as recently as 2016-2017 when India played 13 Tests at home in a single season, their first innings average was 450 and crossed 600 four times.

It is hard to imagine the management opting for a dramatic change in pitches without taking Virat Kohli, Cheteshwar Pujara, Rohit Sharma, and even Ajinkya Rahane in confidence.

It helps that the three of them have captained the Indian Test team at various points in the WTC. But we cannot take away the fact that in a country where runs and centuries are celebrated, they have all risked it for the sake of the team.

In a world filled with anonymous faceless trolls, they are ready to accept increased scrutiny and criticism. This is despite knowing that it might even affect their position in the team, as was eventually the case with Rahane and for a short period with Pujara.

We also need to keep in mind that this coincides with arguably one of the most bowling-friendly eras, which means that things will not get any easier when they travel abroad.

There is a high chance that all of the four mentioned above will finish with batting averages of less than 50. Ahmedabad Test might well be the last time we see Kohli and Pujara together in a series versus England or Australia at home.

The runs have not come as expected and will undoubtedly hurt them. But we cannot ignore the fact that the domination of the Indian test team at home and in the WTC has not only been built on the back of a world-beating bowling attack but also on those batters who are ready to sacrifice their own 100s to score 100 percent points.

Cheteshwar Pujara's 59 at Indore, Virat Kohli's 62 in Chennai, and Rishabh Pant's and Shreya Iyer's countless counter-attacking knocks are worth much more than a big daddy hundred on a flat track.

A win in the WTC final, if India qualify, would be a fitting conclusion to their selfless contributions and unrelenting commitment to the team's cause.

The next set of superstars are almost ready and should consider themselves extremely fortunate to be a part of the team that prioritized victories above runs and has redefined Test cricket in India.