This day that year: India - Pakistan: The match of 271

Some scars never go away; they just don’t – especially when they are close to your heart, especially when they strike a mind which is the process of maturing, especially when they come because your hero fell down just before crossing the line and others with him just refused to put up any fight.

The scars which come with the “I was this close” phenomena, while you are pointing towards the distance between your thumb and index finger while they are touching each other, just don’t go. They just don’t.

Fourteen years ago, the evening of 31st January 1999 gave us one of such scars. And it is still fresh.

Indo-Pak tours have always been more about politics than cricket. About 1999 series, all I remember is that there were a lot of dark clouds of politics over it but let’s just talk cricket for now.

Oh yeah, for the records I don’t believe in the rhetoric ‘Aman ki Aasha’.

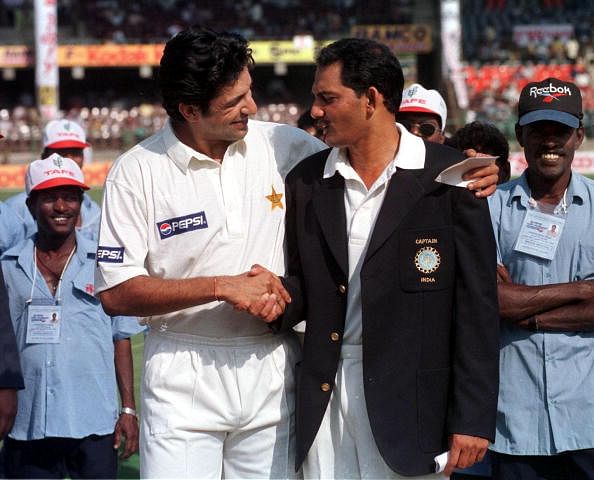

The match was a classic. It was a match between one of the best bowling attacks of modern era and a batting lineup which was close to being invincible in their own den. It was Waqar, the master of swing, Akram, the best left arm pacer ever, Saqlain, the mystery off spinner, bowling to the ‘God of off side’ Ganguly, the man with wrists made of rubber – Azhar, the man with abundance of patience, Dravid and HIM, the God.

The venue, Chennai, had a history of offering good pitches. And if ever there is a time to play in Chennai, it is in winter. Otherwise, you know it all.

We didn’t allow them to score many in the first innings. They returned the favour. It was a meager lead of less than twenty runs which was all we got. Saqlain Mushtaq got five wickets – one of them was of Sachin who couldn’t read the doosra and was out without scoring.

Pakistan started their second innings in a much better way than their first one. The biggest surprise was the batting of Shahid Afridi, logically 19 at that time but I think he claimed to be 17. The slogger played a beautifully crafted Test innings which had a perfect mix of patience and belligerence. As Ravi Shastri would have described it – his madness had method in it.

At 275 for 4, it all looked over for India.

Along with Ravi Shastri, I also felt that something was going to happen. And it did.

At 275/4, thanks to Afridi’s brilliant knock, Pakistanis were looking to explode. Being the unpredictable team they have always been, they preferred the route of implosion.

The man who had always done well against Pakistan, the Aamir Sohail demolisher, the pacer who bowled fast as a surprise weapon, Venkatesh Prasad, with all his height of six foot three, stood up to get counted.

Within no time, Pakistan lost six wickets for 11 runs. Prasad took five of them. Including Afridi’s – his madness took over his method. Venketesh Prasad had made him snapped.

Suddenly we were back in the game – score 271 and the match is yours, just 271.

But was it just 271? Against Wasim Akram who could bowl six balls in more than twelve ways? Against Waqar Younis who, unlike West Indian greats, was more interested in breaking toes than beheading the batsmen, and he was bloody good at it. Against Saqlain Mushtaq who could turn the bowl twice more than Anil Kumble without anyone noticing and could do it in both the directions? Batsmen today know all about doosra, yet they cannot pick Ajmal. In those days, doosra was more mysterious than the Bermuda Triangle.

The chase started like a nightmare. Openers were back in the hut even before the team’s score could reach double figures. The wall couldn’t stand tall. The man with the wrists of rubber and one of the best players of spin fell to his nemesis – Saqlain.

My hope rested on Sachin and Ganguly.

Then it happened. Ganguly drove it and a catch was claimed. After much deliberation Steve Dunn ruled him out – without consulting the third umpire as apparently it was a bump ball. The picture quality of the TV set in my hostel was pathetic to say the least. Everyone around me shouted – it bounced clearly before the catch was taken. I couldn’t see it even after multiple replays. But it was a bump ball – I saw it later on youtube, few years later though.

Ganguly waited, waited and waited. He was waiting inside the ground till the next ball was about to be bowled. Technically an umpire can reverse his decision till the next ball is bowled. It was one of the rare occasions when Ganguly’s technical correctness was bordering perfection.

With five wickets down and almost two hundred more to score, the match was almost over. But again, it was an age when as long as Sachin was at the crease, no TV was switched off. Our only chance was him and it had been like that for last ten years. He, the God himself, was still there.

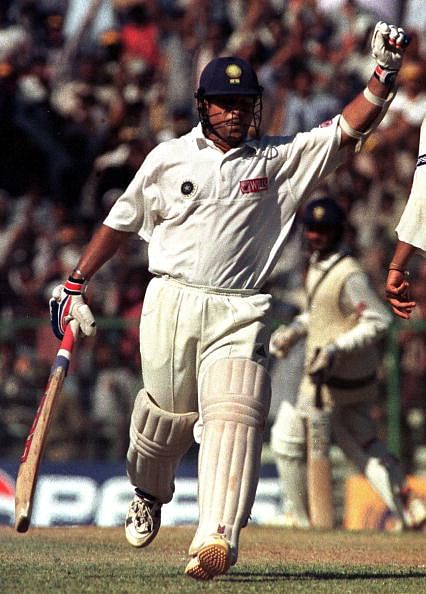

Sachin started resurrection. Actually resurrection isn’t the correct word. Sachin started his magic. Very rarely have I seen someone playing such a high quality bowling with such perfection.

He covered for swing, he read the spin. When he defended, he defended. When he attacked, he attacked. He found a partner in Mongia.

No script is complete without a bit of a tragic dramatization which wasn’t originally accounted for by the audience. There is always a twist in the tale that’s worth remembering.

The tragedy, the devil’s reminder that life isn’t fair, struck from the back. It hit on the back.

Suddenly Sachin started holding his back. The frequency of this started increasing. We could see the physiotherapist making frequent trips to the ground to treat Sachin.

The scenes were strange. Sachin would play a few overs, score boundaries which stretched him to maximum, run like a tracer bullet between the wickets which must have taken a toll on his body, and he would soon be on the ground and getting some treatment from the physiotherapist.

Try lying down on your bed when you get a back pain and let me know how easy it is. Yes, lying down I said and not walking around, leave aside running.

Talk about playing through the pain and all that.

Batting, treatment, batting, treatment, batting – this was going in a loop.

We were getting close, really close.

The hallmark of a champion is that he never gives up. Not when he is getting punched, not when he has been punched down. He just keeps getting back. He just keeps getting better. A champion is always on a lookout for excellence.

The hallmark of mediocrity is that it cannot sustain excellence for long.

This is what followed – mediocrity’s inability to sustain excellence. Mongia, who had been batting so sensibly till now, lost his patience and decided to lift Akram over mid-off. This was just after he had completed his half century – a fine one. Maybe he forgot – it was not the time for “I have done my job” bit, it was the time for “I will see my team home”. It always is.

Mongia’s mediocrity gave up. Akram’s excellence prevailed. Mongia’s lofted shot was caught by Waqar – two Ws had turned the match again.

Yet Sachin was there and we had some hope. His back looked like surrendering but Sachin, the backbone of Indian batting, was not willing to, till the bone of contention was alive.

Sachin found another partner in Sunil Joshi. Another partnership started. I had read about Joshi and his gritty batting in the domestic cricket. In Ravi Shastri’s language – he was no mug with the bat. Joshi was hanging around. He even hit a six – over long on.

We were close, really close.

Don Bradman might have made truckloads of records but if there is one failure for which he is remembered, it is his last innings – those 4 runs. Milkha Singh must have dropped his guard for that one moment and what he missed because of that moment is history. No matter how respected Mr. Vajpayee was as a politician, Babri will always be a blot on his political career.

We all have that one moment in our lives, at least one, when the failure left us with a scar so deep that it haunts for the rest of our lives. No matter how sunny the days become after that, the darkness of that scar doesn’t leave us. No matter how much happiness we get after that day, the pain of that scar remains stitched with us. No matter what happens, we can never get rid of it.

It just doesn’t leave us. Only death can do us apart.

That day, on 31st January 1999, lot of Indian cricket fans got that scar. It was the moment when Sachin got out.

We were seventeen runs away from the victory when it happened. The ball had been given lot of air by Saqlain, Sachin tried to clear the inner field and he mishit it. I don’t know if he misread the length. I don’t know if he couldn’t read it from Saqlain’s hands. I don’t know if it was his back pain which restricted his movements. But he missed clearing the fielder. Wasim Akram, who himself had taken a few insulin injections during the day, was not going to miss the catch. He didn’t.

Sachin was gone. So were our hopes. The doomsday had struck.

The rest of the wickets, as expected, turned out to be a formality. When Srinath was done in by Saqlain between his legs, Pakistanis erupted with joy.

Their celebrations had madness, absolute madness. And all we had was absolute sadness.

Slowly, the Chennai crowd started clapping for the winning team. Pakistanis sensed the mood and took a victory lap as if they had won the World Cup on their own soil. The crowd gave them a standing ovation.

“It is a salute to sportsmanship” said some commentator. I didn’t matter one bit to me.

After the match, the talks of how that behaviour of Chennai crowd could be seen as a stepping stone for a healthy relationship between the two countries, the talks of how this generation was free from the baggage of partition and rosy days were ahead, the talks of how cricket can lay the grounds for peace between the two countries started.

To me, it was all utter bulls**t.

I was right.

Within a few months, we were fighting a war in Kargil.