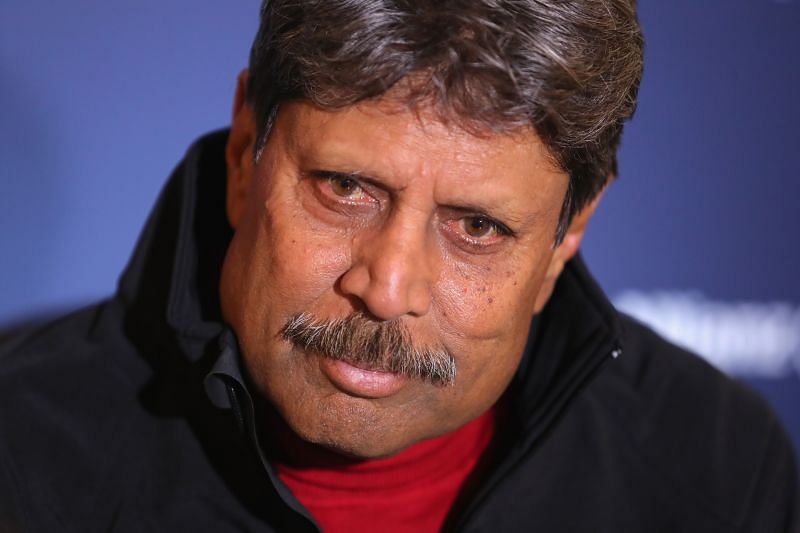

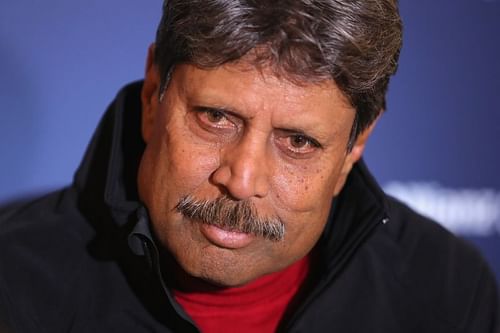

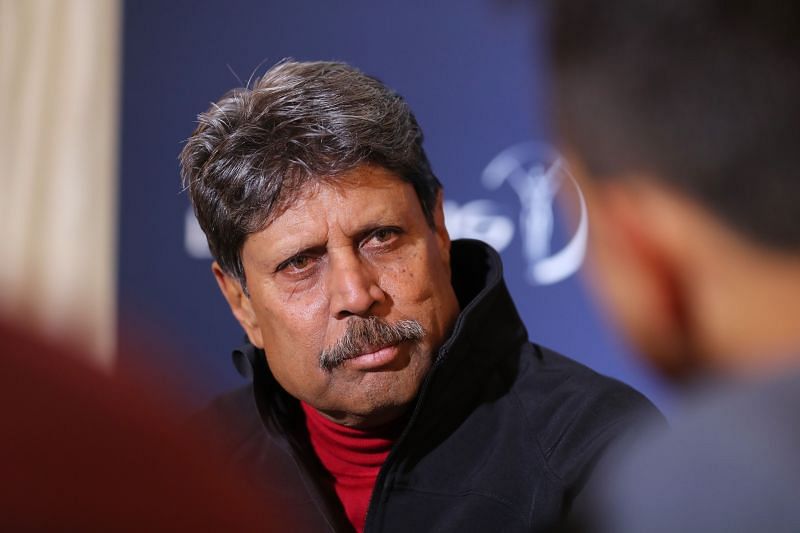

Was Kapil Dev a much better bowler than what his numbers show?

When kapil-dev" target="_blank" rel="noopener noreferrer">Kapil Dev stepped into international cricket, the world was already witnessing the golden era of fast bowlers. Some of the greatest pacers in the history of the sport - lillee/' target='_blank' rel='noopener noreferrer'>lillee/' target='_blank' rel='noopener noreferrer'>lillee/' target='_blank' rel='noopener noreferrer'>lillee/' target='_blank' rel='noopener noreferrer'>lillee/' target='_blank' rel='noopener noreferrer'>lillee/' target='_blank' rel='noopener noreferrer'>lillee/" target="_blank" rel="noopener noreferrer">Dennis Lillee, Bob Willis, Sir Ian Botham, Imran Khan and the great Sir Richard Hadlee - were in action. Then there was the pace battery of West Indies, which included names like Andy Roberts, Michael Holding, Joel Garner and Malcolm Marshall.

But Kapil was unfazed by the competition. Just over a year on from his debut, he was already occupying the no.2 spot in the ICC's ranking of bowlers. He was the quickest to reach the milestone of 100 Test wickets, taking just one year and three months. At that point in time, among the four great all-rounders (Kapil, Imran, Hadlee and Botham) of that era, he had the second best bowling average, behind Botham.

He maintained an excellent strike rate until he reached 200 wickets in 50 Tests. Kapil looked well on course to become the highest wicket-taker in the history of cricket in another six to seven years. He eventually reached that target, both in Tests and ODIs, but it took him much longer as well as a greater number of matches.

As Kapil's career progressed, his strike rate as well as bowling average deteriorated. By the end of his career, these figures, while quite respectable, were not in the same league as, say, Hadlee, Lillee or Marshall. It can be argued that India having a weak bowling attack worked in Kapil’s favor. Otherwise he would have played a lesser number of Tests and picked up lesser wickets.

What went wrong? Why did Kapil Dev fail to maintain his standards while the likes of Imran, Hadlee and Marshall improved with time?

The amazing fitness and stamina of Kapil Dev

Kapil Dev played 131 Tests, almost without a break, in a career spanning 16 years – an astonishing feat for a fast bowler. He also scored over 5200 runs and was an excellent outfielder.

Take for instance Kapil Dev’s career best bowling performance against West Indies – 9 for 83 in the 1983 Ahmedabad Test. Kapil bowled 30.3 overs out of the 60.3 overs played by West Indies. Moreover, he bowled those overs non-stop from one end – a magnificient feat.

The downside of too much cricket

But then, when something seems to be too good to be true, then probably it isn’t. Perhaps Kapil’s performance too suffered on account of relentless cricket. Plus, he carried the burden of spearheading Team India's pace bowling attack on lifeless Indian tracks for such a long time.

While Sir Richard Hadlee was also the one-man demolition army for New Zealand, he operated in much more bowler-friendly conditions. He also played much less cricket than Kapil. Let's consider the number of balls bowled per year up to taking 300 wickets. Kapil bowled almost double the number of balls when compared to Imran and Hadlee.

But do we have any further evidence to back up the claim that Kapil’s performance actually suffered on account of his enormous workload? More importantly, had Kapil played lesser cricket and got more rest, can we say with some degree of certainty what his bowling average would have looked like?

At first glance, it is very difficult to answer the first question in the affirmative. It's also tough to give statistical evidence to reach a conclusion on the second. Kapil took his first 100 wickets at an average of 26.73. But by the time he reached the 200-wicket milestone, his bowling average had already deteriorated to 29.34. This was almost similar to his career end average of 29.65.

Post 1983, his bowling average fluctuated between 28 and 30. Both Imran and Hadlee had a significantly higher average of over 30 when they reached the milestone of 100 wickets. Thereafter, their bowling average continued to improve and they ended their career with averages of less than 23. Doesn’t that simply mean that both of them were much superior bowlers than Kapil in the 1980s?

Kapil Dev's greatest performances

Take a look at some of the most impressive performances by Kapil Dev in Tests from 1980 onwards. By then he had already taken 100 wickets in Test cricket.

In 1981, he took six wickets and scored 84 runs versus England at the Wankhade Stadium in a winning cause.

In 1982, he delivered one of the greatest performances by an all-rounder in a Test match at Lord's. He took eight wickets (just 13 English wickets fell in the game) and scored 130 runs, including a blistering 89 off just 55 balls.

In 1985, on a placid Adelaide Oval wicket, he almost single-handedly demolished the Australian batting and returned with figures of 8 for 106.

In 1986, again at Lord's, in a fine exhibition of medium-fast swing bowling, Kapil broke the backbone of England's batting line-up to help India win the game.

In the same year, he first helped India avoid a follow-on and then tied the Test match against Australia by scoring a brilliant 119.

In 1989, he celebrated his 100th Test match in style, capturing seven Pakistani wickets and hitting a match-saving half-century at better than a run-a-ball.

What is common among all these performances?

The first obvious answer is that all the performances fetched Kapil the Man of the Match award. But there is another, non-obvious answer. All the above-mentioned performances came in the first Test of a series. In fact, six out of Kapil’s total eight Man of the Match performances were delivered in the first Test of a series.

Is this a mere co-incidence or is there a greater truth hidden behind this curious fact? Let us delve a little deeper.

Kapil had a superior bowling record in first Test of a series

Since 1980, Kapil Dev played 32 Tests, which were the first games of the series (this includes a few one-match series too). In these matches, Kapil took a total of 121 wickets at an average of 25.38. In the remaining 74 Tests during the same period, he took 213 wickets at an average of 33.45. The difference in bowling average is more than eight runs per wicket.

No such perceptible difference was observed in the bowling averages of Imran and Hadlee between the first and remaining Tests of the series. Kapil’s superior performance in the first Tests can't be attributed to a few outlier performances as four out of his top five bowling performances came in Tests, which were not the first match of the series.

Let us ponder over this for a while. Often between the end of a series and the start of another, there is a gap of two to three months. Perhaps this gap provided Kapil with some much-needed rest, and he performed significantly better in the first Tests? Thereafter, as the series progressed and Kapil became progressively tired, his performance deteriorated.

And it is not just tiredness, there was injury too. In fact, his knee was operated on for the first time as early as 1980. Thereafter, again in 1984, he went through three knee surgeries in quick succession. Despite this, he never missed a single Test due to either injury or fitness-related issues. India could not afford to give Kapil the rest he deserved and his body needed.

Going by the numbers, perhaps Kapil’s fitness and bowling took a decisive turn for the worse after 1986. More specifically, after India’s famous series win against England under his captaincy. Until this Test, Kapil’s performance in the first game of the series was even more impressive. He took 78 wickets in 15 Tests at an average of 22.94. In 17 Tests thereafter, he picked up just 43 wickets at an average of 30.40.

There is another interesting point which strengthens our argument. Among the top fast bowlers of that era, Kapil had the greatest proportion of scalps of top-order batsmen. 40 per cent of his victims were batsmen with batting positions between one to three. The corresponding figures for Botham, Imran and Hadlee is 31 percent, 35 percent and 37 percent, respectively. Does this point towards the fact that Kapil’s wicket-taking ability fell as the match progressed?

Looking back, this indeed seems to be the case. In those days, Kapil would often provide early breakthroughs by getting two or three quick wickets. But due to lack of support, the opposition team would escape with some fruitful partnerships in the middle order.

In the first innings of the 1982 Lord's Test, England were reduced to 37 for three, with Kapil taking all the wickets. David Gower's fourth wicket was also picked up by Kapil, with England not yet reaching 100. But thereafter, with healthy contributions from Derek Randall, Botham and Phil Edmonds, the hosts eventually made 433.

In the second innings, when England needed only 65 runs to win, Kapil quickly sent the top-three batsmen back to the pavilion. At one stage England were looking distinctly uncomfortable at 18 for 3. But no further wickets fell and England eventually won the match quite easily.

Benefits of sufficient rest

After 1986, Kapil Dev did enjoy success with the ball, but it definitely became a rarity. He performed admirably against West Indies in 1989, taking 18 wickets in four Tests at an average of 21.39. His final hurrah as a bowler was during Australia's tour of India in 1991-92. He picked up 25 wickets in five Tests at an average of 25.80.

In the case of the West Indies series, Kapil had a break of more than three months. He then rested for almost a year before the start of the Australian series. This shows, even at that point in his career, how much Kapil benefitted from some rest.

It all points to the fact that Kapil needed rest to recover from fatigue and injury. This would have prolonged his Test career and also made him more successful. Like Imran, he could have easily developed into a more complete batsman.

Lesson for the future

These facts prove that Kapil Dev definitely belonged to the elite group of fast bowlers who ruled the cricket world in the early 1980s. They also carry a lesson for our generation.

Top-class pacers are a rare commodity, and even rarer are fast-bowling all-rounders. Such cricketers should be handled with extreme care.

The Indian cricket board and selectors failed to do this with Kapil Dev. The BCCI should have nurtured Kapil much more carefully. He should have been preserved for important matches and given rest when he wasn’t fully fit. In the home series versus Australia in 1986, it was apparent that Kapil wasn't fully fit. He bowled just 45 overs and went wicket-less for the entire series.

Kapil himself should share some of the blame for ultimately, it being his body which suffered as a result of excess cricket. The ultimate loser was India, and of course, the entire cricket fraternity.