What’s right or wrong with the Decision Review System (DRS)?

The Decision Review System (DRS) has caught the attention of cricket fans in recent times for both the right and wrong reasons. Though this has been in use for quite some time (DRS made its debut in 2008) across all formats of the game in several parts of the world, DRS has been adopted by the BCCI just recently.

The DRS, in its current form, has had a dramatic debut in India, where the system was put under a serious scanner. It has attracted the attention and comments from a wide section of cricket lovers, and experts have labelled the DRS as, “A game within the game”, “A system with loopholes”, “A tactical tool”, “Not the best use of technology”, “A system empowering the on-field umpires” and more.

Extra Cover: Decision Review System: Explaining the technology behind it

Is the DRS a full proof system? Is it making cricket any different? Does the system need any immediate change?

This article, taking reference to the ICC’s rules pertaining to the DRS, tries to address the above questions by decoding the rules and dissecting the science and arts of DRS. It focuses primarily on three important points related to DRS, which are the umpire’s call, the number of reviews allowed and the use of technology.

#1 The Umpire’s Call

The heart of the DRS is the “umpire’s call”. It is, basically, what the on-field umpire may have taken into consideration with respect to the ball’s pitching, impacting and hitting the stumps whilst making an on-field decision (in case of an LBW decision).

What the rule says

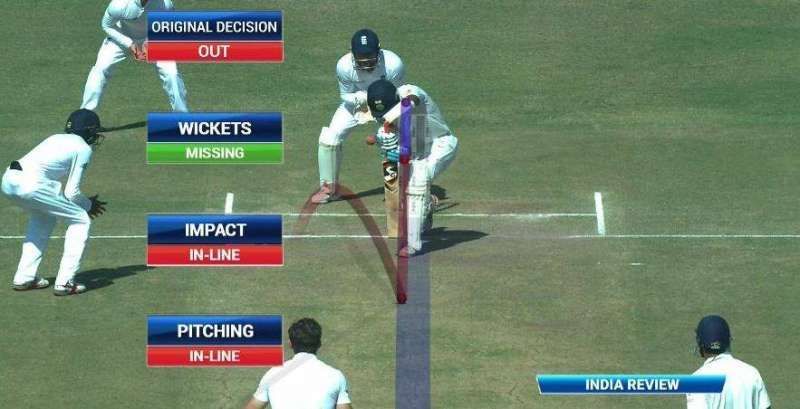

With DRS, the players can review on-field ‘Not out’ or ‘Out’ decisions by requesting the intervention of the third umpire, to review the decision with the help of technology. DRS considers three factors – where the ball pitches, the impact on the pad and hitting the wickets (besides checking if the delivery is a fair one) – while an LBW decision is in review. The core of ICC’s rules for such reviews can be summarised as below:

Scenario 1: If a ‘Not out’ decision is being reviewed, the decision can only be overturned, if the technological evidence shows that all the below conditions are met:

# It is a fair delivery

# More than half the ball is in-line with what is considered to be the zone of impact and zone of hitting the wickets (Red zone shown on TV screen)

# The ball is pitched outside off or inside the zone (Red zone shown on TV Screen) demarcated, with less than half of the ball allowed outside leg stump

Scenario 2: If an ‘Out’ decision is being reviewed, the decision can only be overturned if the evidence provided by technology shows any one of the following:

# It is not a fair delivery

# No part of the ball is either in-line what is considered to be the zone of impact or zone of hitting the wickets (Red zone shown on TV screen)

# More than half of the ball is pitching outside leg stump

What’s right or wrong?

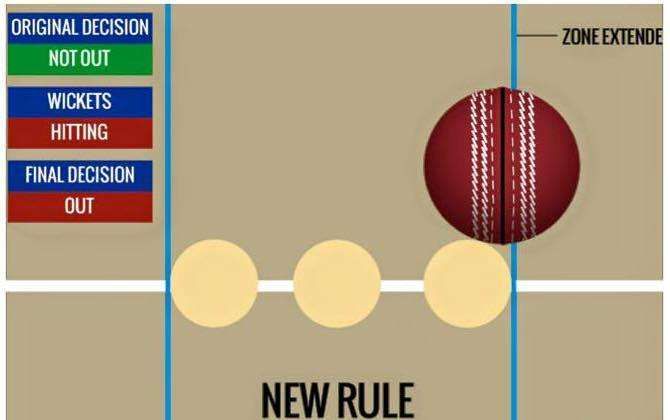

High tolerance given to umpires: As inferred from the rules above, the tolerance given to the on-field umpire is equivalent to the extent of an additional half of the cricket ball on either side of the outer stumps, when it comes to the ball impacting and hitting the wickets within the demarcated zone.

For example, if a decision is given ‘Not out’ by the on-field umpire, to overturn it to an ‘Out’ decision by DRS, the technology must show that at least half of the ball is hitting the wickets (Say all other ‘Out’ conditions with regards to impact and pitching are met). So, the decision remains ‘Not out’ if a portion of 1% to 50% of the ball hits the mentioned zone.

If the same decision is given ‘Out’ by the on-field umpire, for DRS to overturn it to a ‘Not out’ decision, the technology must prove that no part of the ball is hitting the wickets (Say all other ‘Out’ conditions with regards to impact and pitching are met). So, from 50% to 1% of the ball hitting the stumps, the decision stays as ‘Out’.

With the examples above, one can find the variance between the ‘Out’ and ‘Not out’ conditions. The on-field umpire has an extra margin of safety equivalent to 50% of the size of the ball on each side of two outer stumps. Counting both sides, the tolerance sums up to 100% of the size of the ball.

Considering the circumference of a ball is a minimum of 22 cm, the diameter turns out to be approximately 7 cm. One may note that the total distance separating the two outer lines of off stump and leg stump is approximately 23 cm. This means a tolerance of 7 cm in the span of 23 cm is almost 30% of the entire danger zone.

The current DRS rules are laid out as these because the system wants technology to provide a conclusive evidence before the on-field umpire’s decisions can be overturned. One may, however, argue that the game of cricket is played in a narrow safety of margin, where a small mistake may cost a bowler a boundary, a batsman his/her wicket. Considering this, the relatively high tolerance or margin of safety given to the on-field umpires is debatable. It cannot, however, be termed incorrect.

More than one ‘umpire’s call’ makes the probability of a dismissal lesser: Whilst evaluating if a ball is hitting the wickets, the way an ‘umpire’s call’ (represented by the colour Orange) is different from ‘hitting’ (represented by the colour Red) in DRS is that the former is marginal (less than 50% probability) and the latter is with full certainty (100% probability).

By this logic, one may note, the more the number of ‘umpire’s calls’ among the three deciding factors (Ball pitching, impacting and hitting stumps), the lesser the chance of a dismissal. Hence, where the number of ‘umpire’s call’ exceeds one in a decision involving DRS, the decision should logically go in favour of the batsman.

Benefit of doubt shifting from batsman to umpire: The players review part of the DRS has been so hard-coded, that there is almost no room for consultation between the on-field umpire and the third umpire. To eliminate subjectivity, DRS decisions are taken based on only hard facts presented by technology.

On the other hand, for years, cricket has been played by the thumb rule that if something remains inconclusive, the benefit of the doubt should go in favour of the batsman. With DRS, however, it is going in favour of the on-field umpire. The example of Virat Kohli’s dismissal in the India Vs Australia test match (2nd Innings) in Bengaluru was a prime example of this.

#2 Number of Reviews

The number of reviews allowed too has been a point of debate in the cricketing world. This, especially, becomes a critical discussion point in subcontinent conditions, where the volume of appeals for LBWs and close-in catches is high.

What the rule says

The current ICC rule allows no more than two unsuccessful reviews to each team in a span of 80 overs per innings. Reviews are reset every 80 overs. There are, however, no reviews allowed after 160 overs.

What’s right or wrong?

Limited number of reviews: One may remember there is no cap on the number of successful reviews in DRS. Hence, theoretically, the total number of reviews available to any team in a span of 80 overs is infinite. Most teams, however, have poor strike rates with DRS calls. The allowed two unsuccessful reviews in 80 overs is a reasonable one in most conditions, provided the on-field umpires get most of their decisions right.

Umpires are, however, humans and there is a high degree of variability in accuracy of the on-field umpires’ decisions. It becomes extremely challenging for an on-field umpire to get all his decisions right, especially in testing conditions (such as in turning tracks, tracks with variable bounce).

Hence, two reviews in 80 (480 legal deliveries) overs may not often be sufficient. It may not cost the game more if the number of reviews is increased to 3 or 4. It may instead ensure more number of correct decisions and the betterment of the game. With a limited number of reviews available, DRS is otherwise becoming too much of a tactical tool, which it is not intended to be in the first place.

Considering a review unsuccessful if it’s not a fair delivery: It is a no-brainer that the on-field umpire is responsible to judge whether a delivery is fair or unfair, such as to detect, if a delivery is a No ball. It is good in the interest of the game to be able to detect an unfair delivery in DRS than to miss it completely.

It should not, however, take place at the cost of a priceless review. Deducting a review from the fielding team from their allocated quota is forcing the team to pay for umpire’s mistake. This is a double whammy for the fielding team: losing a review and not getting the decision in their favour. The number of reviews remaining for the fielding team in such circumstances should ideally be unaltered.

Reviews are not reset after 160 overs: If an innings lasts beyond 160 overs, the current DRS rules do not allow any reviews thereafter. There is no reason why the reviews cannot be reset after 160 overs in the same way the change of ball is allowed.

#3 Standard technology/equipment set up

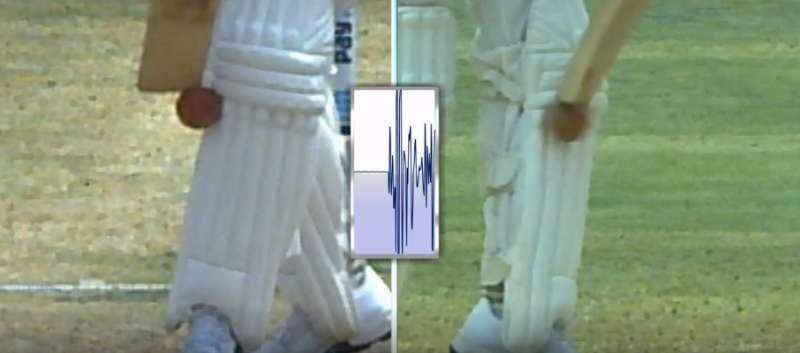

The role of technology and equipment (camera, hardware, screens, audio) is huge for DRS to be a success. Hardware and software form the backbone of DRS. There seems to be, however, lack of clarity in certain areas.

What the rule says

The ICC rules and regulations do provide a standard layout of cameras for the third umpire’s coverage. The set of rules, however, is not precise and clear on using combinations of technologies such as Ball tracking technology, Snickometer/Ultra-edge and Hot Spot technology.

The rule states that a list of technologies may be used by the third umpire but it does not mandate it. For example, Hot Spot technology was not used by the BCCI in its recently concluded home series against England and Australia.

What’s right or wrong?

Lack of standardisation: The usage of technologies should be made uniform for all nations and boards. All boards should adhere to technology combinations and specifications to standards laid out by cricket’s apex body. Hot Spot technology, for example, could be very handy in LBW/bat-pad/ close-in catch decisions.

The objective of the article is in no way to doubt the existence or validity of DRS. DRS is making cricket more error free and is here to stay. The system though needs some recalibration and a strong set of rules and policies to back it up.

For DRS, technology alone cannot serve the purpose unless the processes and policies interpreting the technology are robust and comprehensive. DRS in its current form is good, but has proven to be vulnerable. As it is still in a nascent stage, the ICC must continuously take steps to make it better.