When Patsy Hendren shocked the cricket world by walking out with a three-peak cap, the first cricket helmet

Cricket has evolved over the years to reach a form which would perhaps be unrecognisable to those who were the first practitioners of the sport. The first cricketers, most of whom were Victorian gentlemen, would probably have turned up their noses at the notion of them hitting a ‘DLF Maximum’.

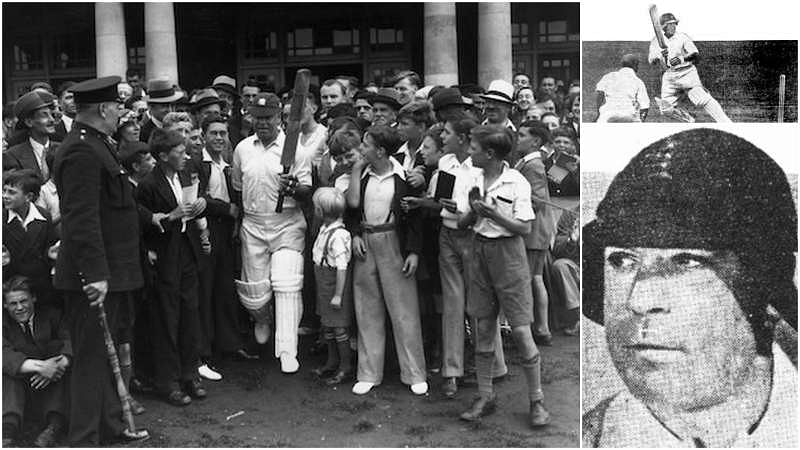

Similarly, when an MCC batsman was seen walking out with the first ever cricket helmet to face the fire of the West Indies pace attack, the crowd sat up in shock. The year was 1933, the scene was the same Lord’s which Sourav Ganguly had desecrated with his hairy-chested celebrations in 2003, and the hero of this tale is the English batting legend Patsy Hendren.

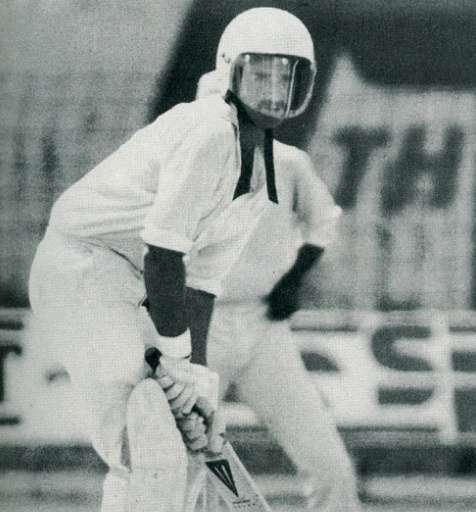

Hendren was not only an entertaining batsman, he was also a popular mimic and a wit of Irish descent, whose antics ensured that there was never a dull moment in the game if he was present. He wore his ‘helmet’ perhaps because he wanted to make the dozing spectators sit up, or perhaps he was genuinely being cautious, but when he walked out to bat on that summer day (May 22, 1933) with the first specially designed protective headgear in cricket, there was an uproar.

Scarves, towels and padded caps had been seen wrapped around heads before, but what Hendren subjected the Lord’s crowd to that day was a huge step in comparison. Abdominal guards and some other forms of protection had also been in vogue by then, but the notion of protecting one’s head as well was something that was still alien to cricket.

His ‘helmet’, or a ‘three-peaked cap’ as it was called by contemporaries, had been made by his wife Minnie. What players wore on the field was not as regulated as it is today, and therefore such homely contraptions, though not very welcome or even common, were allowed.

To the shock of the crowd, what Hendren was wearing on his head had three peaks, as opposed to the one peak a traditional cricket cap has. There was the normal peak in the middle of this ‘helmet’, the peak that bore the emblem of his team. The other two peaks hung towards the sides of his head, the sponge rubber lining on them protecting the sides of his head.

With the blood of the infamous Bodyline series not yet dried, and a battery of pacy fast bowlers at his door, Hendren’s helmet was a merely logical move. It would also turn out to be a revolutionary move half-a-century later, but the reaction then had not been very flattering.

Perhaps what others said to him about his lack of the erstwhile notion of bravery did not sit right with him, or perhaps it was just too hot a day, but the lifespan of the helmet made by Minnie Hendren was very short. Whenever Patsy reached the non-striker’s end, he would hand over the ‘helmet’ to the umpire, and his innings was very short – removed by Constantine for 7.

Outrage follows Hendren’s ‘helmet’, world follows suit 44 years later

As Hendren explained later, his intention was to protect his head from the searing pace of Learie Constantine and Manny Martindale. He was known for his audacious hooks and pulls, but had had to be stretchered off unconscious from the Lord’s ground in a 1931 match after having been hit by a bouncer from Harold Larwood. Instead of cutting down on his attacking batting, he decided to try out this ‘three-peak cap’.

He said, “The people can say what they like. I have been hit on the head four times, once by a Larwood bouncer in 1931 which caused a wound in which six stitches were inserted. I am still suffering recurrent headaches due to that bashing. Believe me, I’m taking no more risks.

“One of Constantine’s deliveries was like a bullet, and if it had hit me I would have gone to kingdom come. My wife made the cap out of cloth lined with rubber. It is a very fine job, but a little bit heavy on a hot day. Nevertheless it protects the temples. I don’t mind my face altered or my teeth knocked out if my head is protected. I don’t think other players will get similar caps. They wear pads and abdominal and chest protectors, but have not the courage to wear a head protector.”

The last line can be read as a jibe aimed at players who wanted to wear protection on the field as long as it was out of sight, but would balk at the thought of wearing protection on their heads, in open view.

Daily Mail commented critically, “Hendren’s three-peak cap has cracked another glorious cricket tradition. No more excited babble of comment was ever caused by novel headgears as began at the Lord’s when a strangely head-muzzled figure, suggesting baseball or fencing and at some angles reminiscent of a bout wrestler, walked in to the wicket. The bowlers got a shock, and diehards dozing in the sun discussing the good old times were electrified.”

Daily Sketch called it “ridiculous”, saying it was “a cross between an airman’s helmet and an Eskimo’s headgear”. The note went on, “Patsy would be well advised to leave this ridiculous contraption in the pavilion, or better still, send it to Australia.”

Hendren reacted to the uproar by agreeing to wear the ‘helmet’ for a few selected bowlers like Larwood, Martindale and Constantine. He abandoned it next season.

There were instances of self-made helmets used by players after this, but it was not until the 1970s that helmets began to be accepted as legitimate parts of a batsman’s gear. It took a century after the first Test match to realise that the head is the most vulnerable part of a batsman. Test cricket saw the first helmet in 1977.

In the 70s, batsmen like Dennis Amiss, Sunil Gavaskar, Graham Yallop and Mike Brearley consistently wore helmets, though what they wore was a far cry from the helmets seen today – what they resembled more was the kind of helmets worn by racing car drivers.

The great Patsy Hendren, whose genius in devising the first helmet often goes unacknowledged, would have laughed at the irony to see one incident from India’s domestic cricket in the last season – Delhi debutant Sarang Rawat was pulled up by authorities for NOT wearing a helmet in a Ranji Trophy match against Vidarbha.