Why Daren Sammy's 'bouncer rule' racism claim is utterly ludicrous

Note: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views of Sportskeeda.

In the midst of the #BlackLivesMatter movement, claims of racism in cricket have perhaps been met with more concern that they would have been earlier.

In 2015, Moeen Ali was called 'Osama' on the field, an incident that was received with only mild indignation when he reported it in his autobiography three years later.

In 2017, Abhinav Mukund revealed that he was ridiculed for the colour of his skin and the cricketing world barely batted an eyelid.

But now, with the fight against racism planting its roots firmly in the ground across the world, many cricketers have decided that this is the right time to make their experiences known and rightly so.

One man has been more vocal than the rest, perhaps because of the scope and extent of his claims.

Daren Sammy's fight against racism

Daren Sammy first alleged that his Sunrisers Hyderabad teammates referred to him as 'Kalu' - a claim that was confirmed when an old Instagram photo of Ishant Sharma calling him the same surfaced.

Sammy is completely justified in demanding an apology for being called 'Kalu'. Irrespective of whether the slur was used in jest or not, if the man does not want to be referred to by it, he should not be.

Click here for live cricket score

But Daren Sammy simply cannot claim that the International Cricket Council (ICC), the governing body of the sport of cricket, changed the bouncer rule to negate the strengths of the West Indies pace attack.

“Looking at the Fire in Babylon, looking at when (Jeff) Thomson and (Dennis) Lillee and all these guys were bowling quick and hurting people. Then I watch a black team becoming so dominant and then you see the bouncer rule start to come in and all these things start to come in and I take it, as I understand it, as this is just trying to limit the success a black team could have," said Daren Sammy.

Immediately after stating this, Sammy said that he might be wrong, almost as a necessary supplement to the ridiculous statement he had just made.

“I might be wrong but that’s how I see it. And the system should not allow that,” he added.

The rise and fall of the West Indies

In 1991, the ICC decided that they had had enough of batsmen who were left to find a new dentist and ruled that one bouncer an over (per batsman) was enough in all formats of the game.

Did the West Indies' pace attack of Joel Garner, Malcolm Marshall, Curtly Ambrose, Courtney Walsh, Colin Croft, and Andy Roberts have something to do with this rule change? Yes.

Did the colour of their skin? Absolutely not.

The cracks in the West Indian castle of glass had already started appearing. Like all great empires, they were destined to fall, but fans just couldn't wrap their nostalgia-driven heads around the fact.

By 1992, Marshall, Holding, Roberts, and Garner had retired. The gum-chewing assertive Viv Richards, who had refused to wear a helmet throughout his career because he found it cowardly, had bid adieu to the game as well.

In the early '90s, the West Indies' legacy was hanging by a thread, but the paper over the cracks was the same colour as the paint. In the decade post this rule change, West Indies' wreckers-in-chief Ambrose and Walsh both took over 300 wickets in Test matches, the highest among pacers. In fact, out of the 8 bowlers who took over 250 wickets in the '90s, 6 were fast bowlers.

Were they any less menacing? To answer that question, in a Test against Australia in 1993, Ambrose bowled a spell in which he took 7 wickets for 1 run, blowing Australia, who were well-placed at 85-2, to smithereens.

In the same series, Ian Bishop terrorised batsmen with his pace and accuracy, finishing as the second-highest wicket-taker, only behind Ambrose.

Did the spicy Australian pitches such as this one at Perth help? Undoubtedly.

But the highest run-scorers in the series were David Boon, Richie Richardson, and Brian Lara - all skilled exponents of the pull, the hook, and the cut. This is no coincidence; this implies that most of the bowlers in that series resorted to the short ball.

Merv Hughes, with his flourishing moustache and angry Aussie swagger, wasn't there to bowl his one bouncer for the over and float a few down at the pads afterwards. Hughes was there to bowl short and bowl fast; he was there to take the head off batsmen who had only recently embraced the concept of a helmet.

Soon after this series, the ICC even relented and allowed two bouncers an over but the West Indies just didn't have the pace arsenal that they enjoyed in the decade before.

Bishop's career would be ravaged by injuries, the most devastating one coming just months after this series - one that would see him out of international action for over two years. Over his 9-year career, he would play only 43 Tests.

Interestingly, in 1992-93, Dean Jones, a man who would later call Hashim Amla a 'terrorist' when he thought the cameras weren't on, somehow decided it would be a good idea to ask Ambrose to remove his wristbands - a moment that has surely given him as many sleepless nights as the Amla incident. The pacer smilingly obliged and then went on to ravage Australia's batting line-up with a 5-wicket haul.

This moment would serve as one of the last reminders of West Indies' Horsemen of Death; the pace attack that had petrified batsmen to their very bones was soon to be but a mere speck in the distance.

From 1995 onward, Ambrose's 6'8" frame could not take the rigours of fast bowling any longer and although he still regularly picked up wickets, he was a shadow of the fire-breathing menace he once was.

The West Indies' team had already started its descent into a ravine of mediocrity, but cricket romantics were so hung up on yesteryear that any claims of the Caribbean dominance dwindling were met with unreserved chagrin.

The era of Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson

Daren Sammy's other claim is that the ICC did not have a problem with the intimidating fast bowling of Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson.

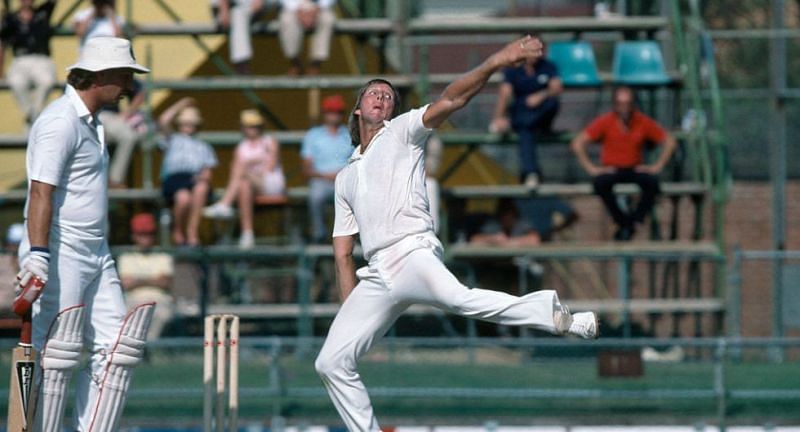

In a first-class match at the Bankstown Oval in 1973, 23-year-old Jeff Thomson was bowling so quick that the slips and the keeper were stationed closer to the boundary (which was many yards longer than the current international standards) than the stumps.

Still, Thomson managed to clear the keeper with a bouncer that hit the sight-screen on the full. He also shattered the eye socket of a batsman named Greg Bush, and the next batsman who walked in saw Bush's blood splattered across the crease and the stumps, and took guard without a second thought.

Thomson made it into the Test squad soon after and unabashedly stated that he loved watching batsmen bleed. If Jofra Archer had asserted that he had enjoyed rattling Steve Smith's grille in the 2019 Ashes, he would have been cast out of society and thrown to the wolves.

When boxer Deontay Wilder (a major voice in the movement against racism) suggested that he would like a 'body on his record', unrestrained criticism poured in from all parts of the world.

As a society, we have become less tolerant of the intrinsic violent tendencies of humans. Instead of acknowledging them and appreciating those who don't act on them, we are trying to force people into pretending these proclivities don't exist. But this new-found desire to sanctify human thought is indeed very new-found.

In 1976, Dennis Amiss wore a helmet for the first time in a televised game and was mocked, almost as if his desire to not die on the pitch was an act of pusillanimity.

In 1978, Australian skipper Graham Wallop wore a helmet for the first time in a Test match and was met with resounding jeers from all corners of the ground.

Tony Greig hit out at the introduction of helmets and stated that bowlers would target batsmen more now that the men with willows weren't in mortal peril.

In all likelihood, if the ICC had introduced such a rule in the age of Lillee and Thomson, it would have been met with as much - if not more - disdain from the batsmen as opposed to the bowlers.

Even as late as 2006, Justin Langer was hit on the head by South African Makhaya Ntini, incidentally a man of colour who finished as the highest wicket-taker among pacers in Tests in the 2000s.

The current Australian coach, who made his debut in the aforementioned 1993 West Indies series, bravely stated that the blow was more psychological than physical. Although the toughest man in cricket history had to be taken off with a concussion, the sport not so much as turned its head in a cursory glance.

Cricket is now susceptible to the trends of the world

Instances like the unfortunate demise of Phil Hughes have since added their pinch of salt in the pot, and for the first time in centuries, cricket has surprisingly found itself susceptible to external influence.

The sport is no more just a sport; it is a platform for expression and the people who have reached the highest level have earned the right to put their outreach to good use.

In the transformation from the era of unbridled hostile aggression to the current epoch of concussion substitutes, cricket has come a long way. Daren Sammy is blurring the fine line between correlation and causation, and by doing so, he is abusing his power as an ambassador of the sport.

Cricket is a beautiful sport. Despite having its roots in colonialism, the Gentleman's Game still manages to be a great unifying factor, and we cannot allow Daren Sammy's frankly outrageous conspiracy theories to tarnish the game we so dearly love.