Why Dhananjaya de Silva was ruled "not-out" despite a hit-wicket

Riding on the back of a superb 115 from Kaushal Silva, Sri Lanka finished day-4 with a vital 288 run lead. Silva batted all of 269 balls to anchor the Sri Lankan innings as the hosts looked to press the advantage against an under-fire and under pressure Australia. As Silva batted beautifully for a well deserved hundred, the middle-order chipped in with timely contributions to frustrate the tourists. And it was the Sri Lankan middle-order that produced a moment that left onlookers both puzzled and scrambling for the closest available run-book.

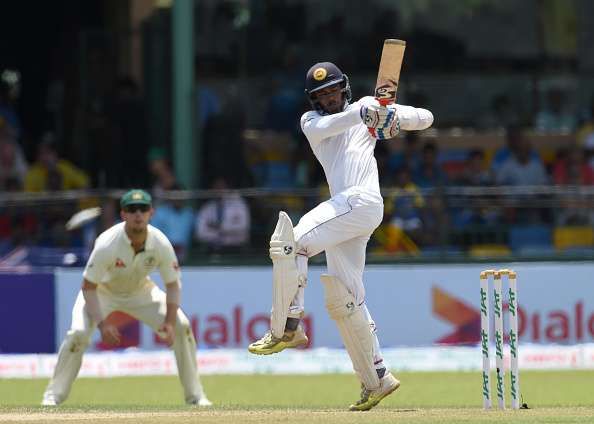

As the Australian pacers continued to pound away under the warm afternoon sun at Colombo, Dhananjaya de Silva played a flick shot off his pads. While he didn’t make contact with the bat, the ball flicked his pads and was duly collected by Peter Nevill who followed up with an appeal.

Dhananjaya de Silva – the centurion from the first innings – quite confident and unperturbed with the appeal, went about his post-shot mannerisms. This included a rudimentary repeat of the attempted shot, a step forward, then back and a swing of the bat. Somewhere along that routine, his bat flicked the stumps and a bail was dislodged. With a sheepish smile, the right-hander promptly picked up the bail and placed it back where it belonged.

Australia, having toiled hard all day, sensed a whisker of an opportunity. After all, the batsman had just played the ball and in the midst of an appeal, had dislodged the bail while seemingly in follow-up mode. Hit-wicket? Why not?

Sure enough, video replays confirmed what had just transpired. Dhananjaya de Silva had indeed dislodged the bail but the umpires ruled him not-out. But why not, the onlooker might have argued.

Here’s why.

The moment evoked two cricket laws, Law 23 (Dead Ball) and Law 35 (Hit-wicket). Per Law 23, the ball is deemed “dead” when it is finally settled in the hands of the wicket-keeper or of the bowler. Whether the ball has finally settled or not is a matter for the umpire alone to decide. That said, when the ball is deemed “dead”, the batsman cannot be ruled “out”.

Law 35 now. The hit-wicket is perhaps a common mode of dismissal in gully cricket and needs no introduction. Per the law however, the striker is out “hit-wicket” if, after the bowler has entered his delivery stride and while the ball is in play, his wicket is put down by his bat. The striker can also be out “hit-wicket” if he dislodges his stumps in the course of any action taken by him in preparing to receive or in receiving a delivery. While the former did occur in the said incident, the latter didn’t as the bails were dislodged after the batsman had faced the delivery. And while the former, i.e. putting his wicket down with the bat when the ball is in play – keeps the case alive, the keywords are “ball in play”.

With Neville having gathered the ball and a lengthy appeal ensuing and subsequently concluding, the ball was deemed “dead”. And video replays confirmed that there was sufficient gap between the keeper gathering the ball and the batsman flicking the bail, thereby confirming the employment of Law 23 to rule the ball “dead”.

The Australians, having been witness to all that transpired, perhaps knew all too well that the ball was “dead”. Needless to say, Dhananjaya de Silva knew that he was safe as well as he displayed a broad smile as the whole event played out. But the situation of the game, coupled with gamesmanship from the tourists meant that the incident came under the third-umpire’s scanner and served us a lesson in the Laws of the game. Another reminder that a “dead ball” isn’t a death knell for the batsman – one of the several dichotomies of the game.

Also read: Top 5 pacers with most wickets in a Test series in Sri Lanka