Has WTC final loss shown that India's batting is just not good enough?

India choke in key matches. Virat Kohli’s captaincy has issues. Did Kane Williamson's superior temperament win it for New Zealand? Why did Jasprit Bumrah play ahead of Mohammed Siraj? Why did India play two spinners?

The cricketing world seems divided with their opinions and analysis on why India lost the World Test Championship (WTC) final to New Zealand.

First of all, despite the rains and the uncertainties, the WTC final was a hard-fought contest between two good sides. The bowling, aided by the conditions, was top-notch, which made batting incredibly difficult. Nevertheless, both sides pressed for a win, with New Zealand expectably faring better than India.

India’s concerns were highlighted in a previous article before the Test, and most did return to haunt the side.

First of all, India never started as favorites. New Zealand entered the grand finale as the top-ranked Test side. They were also the better-prepared side, having played two Tests in England in the build-up to the WTC final. India, who haven't featured in a Test since March, played only one intra-squad match, that too in sunny conditions.

The weather in Southampton during the big match was much closer to what New Zealand experience when they play at home. And the Kiwis champion their home conditions like no other side. Their win-loss ratio at home in the past six years is 17, even better than India’s incredible tally of 11.

Since 2015, New Zealand also have the best win-loss ratio in England, with the two victories this month propelling it to a mighty three. On the other hand, India’s win-loss ratio on English soil reads a dismal 0.2.

New Zealand were expected to bat and bowl better. India’s strength in recent times has been its bowling. They fared well with the Dukes ball, but they needed to bat better than they did in their recent past.

Moving ball – India’s Achilles’ heel

In the first decade of this century, India competed better in England and New Zealand, where conditions helpful for swing bowlers. In 2002, India drew in England and five years later won one. In 2009, India also won a series in New Zealand. Since then, the three tours to England and two to New Zealand have been filled with disappointment.

Unlike the trio of Rahul Dravid, Sachin Tendulkar and Sourav Ganguly, the current batch struggle against swing bowling. Except for Virat Kohli, no batsman in the current squad averages over 35 in English and New Zealand conditions.

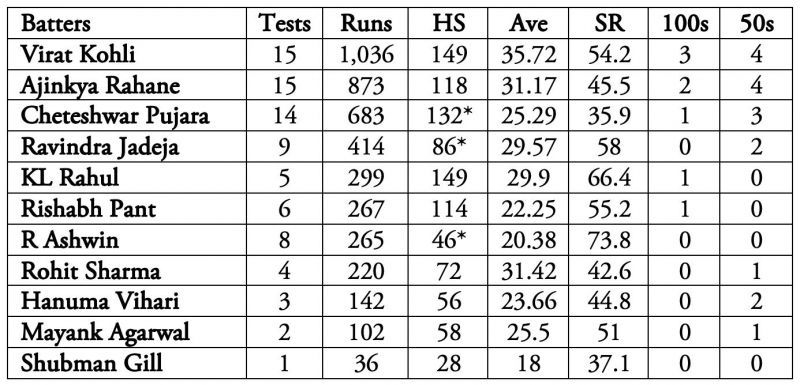

Current Indian batters’ numbers in England and New Zealand

The New Zealand bowlers exploited the weakness through discipline. If India do not find an answer to the problem, the likes of James Anderson and Stuart Broad will relish the opportunity against this brittle line-up.

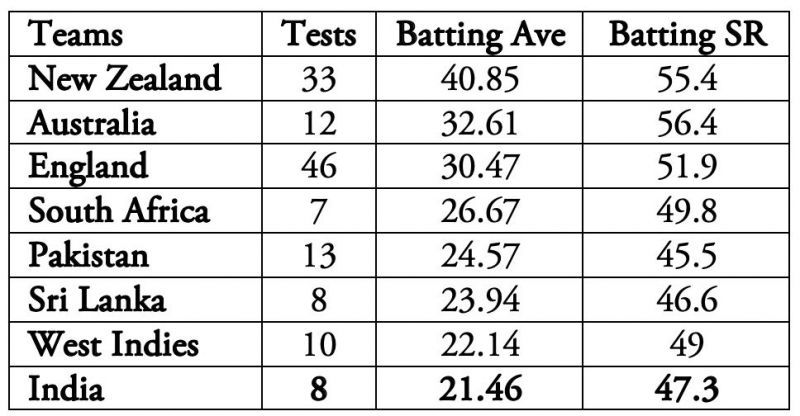

Team batting averages in England and New Zealand since 2015 (minimum 5 Tests)

What about the solutions? In a country as vast and diverse as India, there are varied conditions spread across the geographies. It’s not just dustbowls. Like Dharamsala, the administration needs to identify other locations across the nation where it swings considerably. There could be camps for all groups in these conditions to ensure the moving ball doesn’t remain a weakness.

Is Virat Kohli’s method of showing intent the answer?

Virat Kohli believes that the Indian batters let the New Zealand bowlers dominate by not looking to score runs. Every time the word ‘intent’ is spoken of or implied, the spotlight falls on Cheteshwar Pujara.

The Test had an average run rate of 2.5. Pujara’s strike rate was just over 17, which is just around one run per over. Not that he scored too many, just 23 in the match.

Pujara has been a worry for India in the WTC for two years. Despite some crucial outings in Australia, he averaged just 28 in the tournament and while playing overseas, the average further dropped to 25.22. His strike rate is also below 30, which means his primary role is just to take the shine off the ball and make the bowlers weary.

But can that be the only role of a no.3?

Australia and New Zealand have done exceedingly well in this position during the timeframe. For example, Australia's Marnus Labuschagne and Pujara have ended up playing 95-105 balls per innings, with the former getting 60 odd runs and the Indian less than half of it.

One of the finest bowlers of all time, Dale Steyn, who had bowled to Pujara in his early days, pointed out that the Indian no.3 has lost a part of his game by cutting down on shots off the back foot. Steyn told ESPNCricinfo:

“I’m so used to him rocking onto his back foot and playing with his hands and good feet movement. He’s kind of lost that part of his game. And if you’re only hanging on the front foot, good bowlers will not bowl half-volleys to you.”

Virat Kohli’s lean patch and Ajinkya Rahane’s lack of consistency have compounded the problem further. India haven’t done well between the positions of three and five in the recent overseas Tests. Since 2020, in away Tests, the positions have contributed 103 runs per innings at an average. In contrast, it’s 163 for Australia and 120 for England.

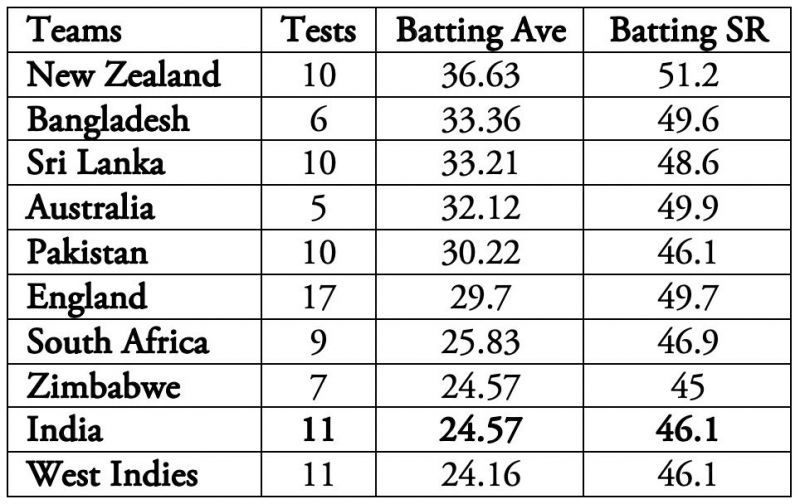

Team batting averages since 2020 (minimum 5 Tests)

While the batting struggled, it was the bowling that kept India in the hunt. Since 2018, no team have come close to India in terms of their bowling prowess. This has been the main reason behind India’s dominance.

After the match, Virat Kohli said:

“The idea from here on will be to try to score runs and not worry about getting out in testing conditions. That’s the only way you can score and put the opposition under pressure, otherwise, you are just literally standing there hoping that you don’t get out and eventually you will because you are not optimistic enough.”

While clarity in thought is a good sign, Pujara’s approach and form is part of the problem. Kohli’s solution may not be the correct one.

Kane Williamson was the only batsman to reach the three-figure mark (both innings combined) in the WTC final. Indian bowlers didn’t get as much swing as their Kiwi counterparts, but that didn’t stop them from bowling in the right areas and getting movement off the pitch.

Williamson curbed the extravagance and his natural game to fit the conditions. He left aplenty, got beaten, took the blows, played the ball late and with soft hands. When the bowlers were tired or looked to attack by luring him, he capitalized and got the scoreboard moving.

He also let the tail play their game and trusted them. There was a plan, which was situational. There was no stubbornness at the extreme ends of the intent spectrum.

The Great Indian Tail is where India lost it

The tails of other teams have been a matter of great concern for India. Whether it is fatigue, complacency, or simply lack of planning, the area has hurt India.

While batting, their own tail has been a massive reason for their miseries. And none of the above mentioned reasons work here. It’s a matter of intent. The intent is to be there, grind and make it count.

They have consistently won you matches with the ball, but they need to do much more with the bat as well.

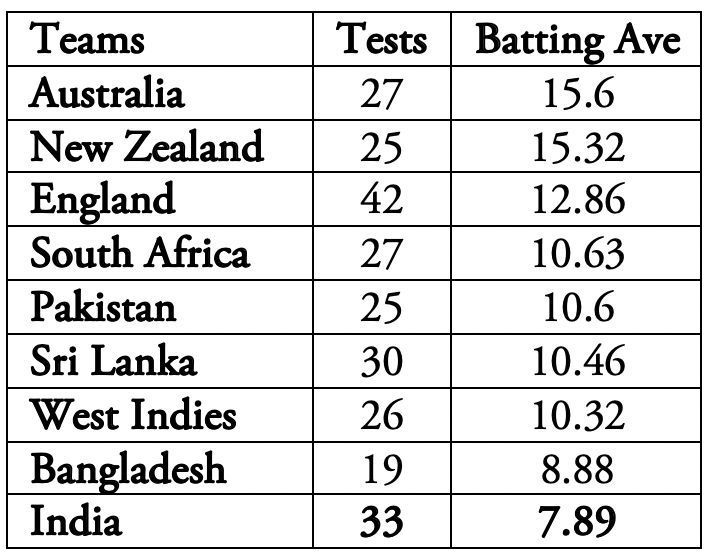

Team batting averages from No.9 to No.11 since 2018 (minimum 10 Tests)

In a closely fought contest, India majorly lost the game in their batting contribution from the tail. In the 86th over, India were 205 for 6 in the first innings. 250 would have been challenging enough. But they were bowled out for 217. In the second innings, it took India 62 balls to be 170 all out from 142 for five.

In contrast, New Zealand lost their sixth wicket 20 runs short of when India did the same. They still ended up securing a 32-run lead. India’s last four wickets fell for 12 runs in the first innings and 14 in the second. New Zealand’s last four wickets fell for 57 runs on a deck where it's tough to bat and every single run mattered.

Over the past decade, Virat Kohli has shown his ability to find ways and score runs everywhere. If he does that, India will be better placed against England. Will that be enough? Wasn’t that the case in 2018 too? Will the intent only get them to cross the hurdle?

India are a top side, high on self-belief, with proven performances. There is no reason why addressing the main issues won’t help them win in England. But the first step here is acknowledging the handicaps.