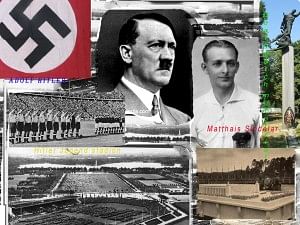

Breaking the myths surrounding Adolf Hitler and German football

“The day was 7th August 1936, as Germany faced Norway in the knockout rounds of the 1936 Berlin Olympics. Norway was a team, against whom the Germans had been undefeated since their last eight matches. However this match, unlike the others, was different as it had a very special guest among the stands.

"The Fuhrer, along with his group of ministers, had gone to Berlin’s Poststadion, to lend their support to Otto Nerz and his German team. It was Adolf Hitler’s first football match and he was clearly trying to use the games as a propaganda and a means of gaining prestige at that time.”

Throughout history dictators have used sport as a means of political propaganda. The history of politics and football looks at how Europe’s right wing dictatorship pounced on the working man’s sport as a means of drumming up support for their personal ambitions – be it Franco in Spain, Mussolini in Italy or even the Nazis in Germany.

Football was not only a way of showing support, but also served a strategy to spread one's political influence.

As I browse through forums, time and again I have come across debates between Cules and Madristas about Franco and his support to the capital club, or even stories of Mussolini attending club matches, and about how their influence changed so much of the history of their club. One question which always kept me intrigued was about Germany’s dictator and the club he supported.

I had read stories about Nazis and their influence on football, like the Nazi salute, the Matthais Sindelar incident, or the removal of Jews from all organizations. As I put this question across while digging for answers, I stumbled upon quite interesting and varying responses.

“It has to be Bayern Munich” said a newbie. “How else are they the most successful club in German history?” “It could be a club from Berlin, the capital club,” said another. “It was Schalke, the most successful club during the Reich," said one confidently. “It has to be Nurenberg, that’s the reason they go by the name ‘Der Club’, it clearly shows their support to Hitler”. Some went as far as finding clubs from Hitler’s birthplace in Austria and came up with names such as LASK Linz.

"The match commenced with Germany in control, as expected. The Germans dominated but were unable to convert their chances. Norway on the other hand had hardly managed to even cross the halfline. The young August Lenz from Germany had already missed two sitters.

"As Germany pressed, Norway finally found their break and dashed towards the German goal, ending up scoring from their first shot on goal. Hitler was agitated and started throwing tantrums, unable to control himself.”

‘Der Club’ – that’s what 1.FC Nurenberg are known as. Many in today’s time relate it to the Fuhrer himself. But no, Hitler’s influence had more to do with the city in general rather than just around a football club.

The term ‘Der Club’ actually dates back to the early 1920s, when Nurenberg were simply the best team in Germany, and the name was born out of respect for the club. Some historians argue that the term was used as early as 1907, but the name was only known around a few parts in the state of Bavaria. By the year 1919 ‘the club’ became quite a widely used nickname. Even Nurenberg’s footballers and members were referred to as Cluberer.

It’s true that Hitler had a special connection with Nurenberg. But the closest Hitler came to be associated with the club was with its stadium. The Franken Stadion was used as a marching ground as well as a place where Hitler gave some of his famous speeches. The home ground of Nurenberg today was known as the Hitler-Jugend Stadion back then.

Nurenberg went on to be the most successful club in the 20s and early 30s. In the year 1934, they lost in the final to FC Schalke, a club that would go on to become the strongest side during the third Reich. Nurenberg would capture titles just before and after WW2 – in 1936 and 1948.

In 1998 ‘The Times’ published an article, ‘The 50 worst famous football fans’. The article claimed that Hitler was a Schalke fan. It met with hard criticism, with the Schalke board even sending a notice to the magazine. The accusation by the magazine was purely based on the fact that Schalke were simply the best team during the Nazi era.

Schalke’s rise to power came in 1933, just six months after Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany. In 1934 Schalke won the national finals and with that laid the foundations of a new era of German football dominance. In players such as Fritz Szepan, Ernst Kuzorra, Hans Bornemann, Rudi Gellesch and Adolf Urban, Schalke had the best squad in the whole of Germany (many among them represented the German NT).

Employing their style of the famous ‘spinning top’ (Schalke’s quick passing, keeping the ball on the ground and looking for a well positioned man style of play), Schalke went on to win the regional championship 11 times between 1934 and 1944. While most footballers were given obligatory duties for going into war, the German national coach managed to make sure his best players were exempt from such situations (Fritz Szepan and Ernst Kuzorra worked at an airbase near Gelsenkirchen, but Adolf Urban was an exception – he lost his life while fighting the USSR in Stalingrad during the later stages of the war).

Another reason for Schalke’s success during the Reich era was that almost every player on the squad had been playing in the same team since childhood – they were mostly sons of miners or industrial workers in Gelsenkirchen. Some first team players were even from the same family. Schalke were objectively the best team of that era, based simply on merit rather than influence from the higher ups.

The theories of Bayern Munich or Berlin-based clubs being used as propaganda clubs are based on pure fantasy and misconception by newbies or supporters of other leagues. Berlin was the heart of football in Germany only during the pre-1900s. Other than the Olympiastadion, which was used as a base for political speeches, most Berlin-based clubs were not as famous as their western or southern counterparts.

During the year 1932, Bayern Munich had won their first national title. There was every reason to believe that the club from south Germany had a bright future ahead. But unfortunately for them many of Bayern’s fans, club members as well as their club president were Jews. And like many other Jewish clubs, they suffered.

The president and many of their members departed, leaving the club in turmoil. Bayern however stood by their Jewish members and made it clear that they were accepting orders from above only under protest. This stance of theirs made the Nazis feel that 1860 Munich was a more trustworthy club, and they helped the Blues whenever needed. It would take Bayern more than three decades to regain the strength they once had.

Hitler, the man who grew up in Linz, was not a fan of football, but the Nazis did use football as a means of propaganda. The Nazi influence on football in general ran deep. From the Austrian Anschluss, which gave a combined Austrian and German national team, to the death of Matthias Sindelar and the infamous death match between German soldiers and players from Kiev, the Nazi impact on football was strong. Teams were made to do the Nazi salute as well, in addition to being forced to play patriotic songs prior to a game.

Hitler believed in having a firm and strong youth, and so laid greater emphasis on sports such as boxing and athletics. His influence on football in Germany was limited. However, during the rise of the Reich, the Nazi party appointed Felix Linnemann as the head of the DFB. Linnemann controlled the DFB, right from the appointment of coaches to the selection of players; the Nazi party used Linnemann to spread their political ambitions on the game.

The bottomline, however, remains that Adolf Hitler was not a supporter of any club, and was never involved in any football activity. The 1936 Berlin Olympics is the only known instance of him ever watching a football match.

”Germany pressed harder, with Nerz even ordering the defenders to attack. But once again it was Norway who caught Germany on the break with Isakson slotting one past the goalkeeper. Hitler could not contain his rage. He immediately rose and left, never again to be associated with football….”