Analysing FIFA's eligibility rules

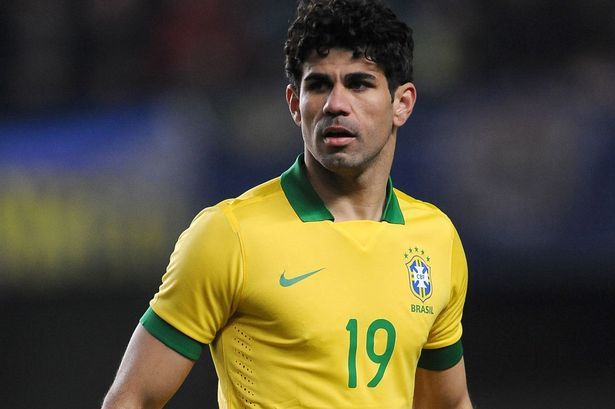

Diego Costa's decision to turn out for La Roja and shun the Selecao's famed yellow jersey has put the spotlight back on the choices available to players in picking a national team to play for. But it is by no means an isolated incident - only the one with the highest profile.

This year’s World Cup is ripe with numerous such examples.

Jurgen Klinsmann's deliberate approach to look for American talent within his native German shores (and beyond) has received criticism from some quarters - notably former United States manager, Bruce Arena.

The Swiss squad features only eight players who have no ties to other nations, and at the far extreme end, the Algerian squad is primarily composed of players born in France (15 out of 23!). In fact, France seems to have taken up the role of prime supplier, with there being 24 French born players in Brazil who will not be representing France.

Enabling player movement is not necessarily unhealthy. In an increasingly global world, and with as global a sport as football, there is more than enough room for players' choices to be accommodated. Ivan Rakitic's story - his father cried when his son, born and raised in Switzerland, chose to represent his homeland, Croatia - is a reminder of the joy football can bring.

The sheer increase in the number of players changing allegiances (as of March 2014, FIFA has processed 174 association changes for male players since 2007) however, merits a look at the rules which make this possible.

The FIFA statutes allow players to change nationalities only if he has never appeared in an official FIFA competition match and satisfies either of the following conditions with respect to his desired 'new' nationality:

- He was born there.

- His biological father or mother was born there.

- His grandmother or grandfather was born there.

- He has lived there continuously for at least five years, after reaching the age of 18.

This unfortunately, allows players like Costa to switch allegiance from Brazil to Spain, despite collecting two caps for the Selecao in friendlies - since a friendly is not part of an official FIFA competition. Thiago Motta, formerly of Brazil, now of Italy, featured in the Gold Cup - an official FIFA competition - for Brazil. But since Brazil were invited as a guest nation to participate in the tournament, he retained the option to switch to Italy on a technicality.

Allowing players to put countries on trial - and that is exactly what Costa and Motta did - does not help enhance the nationalistic appeal of international football.

What this definitely does do though, is encourage countries to call up players for competitive matches at a younger age. The rather unsavory fight for Adnan Januzaj is a reflection of the pressure football associations are under to secure young talent, not just to enhance their talent pool but also prevent potential opponents from securing an exciting prospect for themselves.

Januzaj was born in Belgium, but his family hails from Kosovo which is his parents’ birthplace, with Januzaj regularly spending his summers in the newly recognized nation. He is of Albanian heritage (presumably, his grandparents are Albanian but this remains unclear) and his maternal grandparents were born in Turkey. Even Serbia could lay claim to Januzaj, due to the disputed political status of Kosovo.

In total, Januzaj was eligible to play for five different football associations, four of which publicly coveted his services (minus the Serbians). A fifth rather misguided nation, England also joined the fray – but more on that later. All this, before he turned 19.

The present criteria however, restricts player movement to a far greater extent than the practically non existent erstwhile regulations. Real Madrid legends Alfredo di Stefano (Argentina, Colombia, Spain) and Ferenc Puskas (Hungary, Spain) represented multiple nations, playing for Spain in the latter part of their careers. Puskas even represented both nations at different World Cups. Michael Platini, at the end of his career played in a friendly for lowly Kuwait, at the express invitation (and likely, monetary remuneration) of the Emir.

To put to bed what was clearly an oversight in their governing regulations, FIFA has implemented a series of significant changes in recent years, leading to the current criteria – which require that there be a ‘clear connection’ between the player and his country of choice. This clear connection is either a reflection of the player’s heritage and ethnicity or one which is forged through years spent living in his adopted country.

The Home Nations – England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Island – take this one step further. In an agreement amongst themselves, ratified by FIFA, they narrow their definition of ‘clear connection’, getting rid of the residency clause, while allowing players with a minimum of five years of education (before the age of 18) in the relevant association to be eligible to play for them. This rules out Costa-like defections, and is the reason why England were in fact, contrary to widespread media reports, not in a position to field Januzaj.

Is this a disadvantage? Maybe. English managers have in the past displayed surprising obliviousness when it comes to the Home Nations Agreement. Roy Hodgson spoke of the possibility of Januzaj representing England and Fabio Capello wanted to give call ups to Spanish pair Manuel Almunia and Mikel Arteta. There exist similar examples concerning the other Home Nations as well – Nacho Novo and Scotland, Angel Rangel and Wales. In all cases, amidst confusion, clarifications were needed and managers’ well thought out plans had to be shelved.

But the Home Nations’ commitment to upholding this gentleman’s agreement is commendable. Their arguments, that national connections are better forged when young, and that the existing FIFA regulations are not good enough to prevent the dilution of national teams hold considerable weight.

FIFA would do well to consider adopting the Home Nations Agreement and applying it on a global level, and extend the official FIFA competitions clause to include friendlies. Otherwise, with the amount of oil money flowing into club football, who is to say that we might not see a Middle Eastern national team composed entirely of Brazilians at some point in the future?