Busting 4 myths of the football finance world

The football industry is shrouded in mystery when it comes to its finances. A lack of standardisation, the rampant spread of fabricated news on social media and the private ownership of football clubs often lead to fans feeding on the wrong information.

Traditionally, the finances of a football club are made public if the club’s shares trade on stock exchanges. However, in today’s data-driven world where financial performances are scrutinised for decision-making by investors, stakeholders and fans, clubs usually disclose their finances.

Many football fans across the globe are under the false notion related to some practices in the football finance landscape. This article aims to educate the readers about a few of the widespread misconceptions prevalent in the sport today.

Busting four popular myths about the world of football finance:

#1 Net-spend is an improper metric to measure the financial performance of a football club

Owners and fans measure the performance of their football clubs in terms of trophies won and league position.

A school of thought developed over the past few years has advocated measuring the success of a football club by the net-spend it has incurred over the season. Simply put, net-spend is the amount spent on acquiring new players deducted by the amount recouped by selling existing players.

Net-spend is an appropriate metric to measure the efficiency and shrewdness of a football club in the transfer market. However, only considering it relative to success is inappropriate and shortsighted.

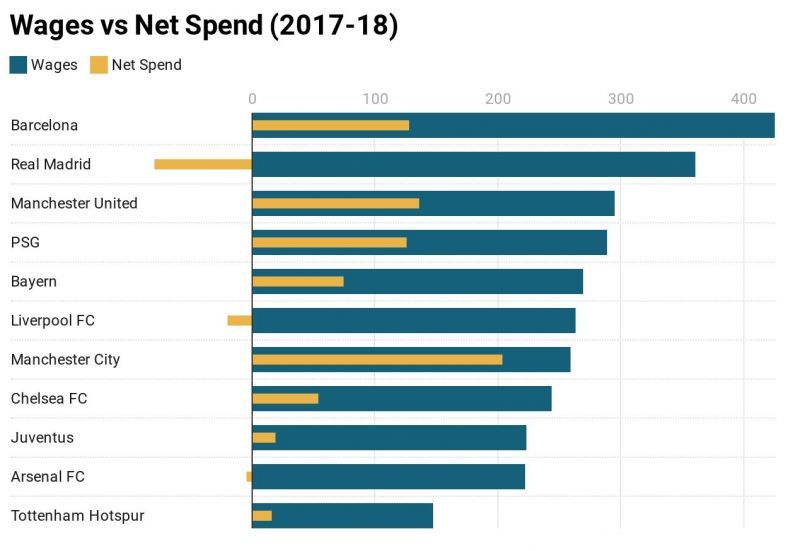

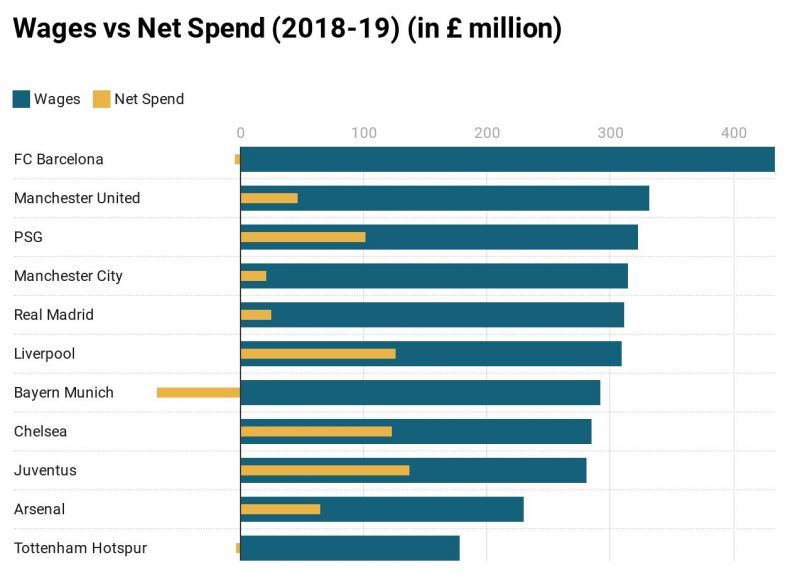

Player wages occupy the biggest space in a football club’s expense side of profit and loss statement. High wages easily dwarf the transfer fees paid by clubs thus it makes more sense putting a higher weight on them. The adjoining charts of European football clubs for the 2017-18 and 2018-19 seasons show the wide disparity in amounts between net spend and player wages.

Another point to be considered in this regard is that of players on loan deals and free-agent signings.

Aaron Ramsey switched to Italian champions Juventus in the summer of 2019 as a free agent. Juventus paid £0 as a transfer fee but ended up paying a massive £400K/week wage for a 4-year contract. On crunching the wage numbers, Juventus are effectively buying Ramsey for an eye-watering £83.2 million.

The same was the case with Radamel Falcao’s loan signing by Manchester United, where £0 was paid as transfer fee but a £265K/week wage translated to buying Falcao for £13.7 million for a year of his services.

Hence, wages paid to football players should be considered ideally over net spend when comparing the financial performance of football clubs.

#2: Jersey sales do not cover the cost of buying a football player

Football clubs usually sign a multi-year sponsorship deal with big sportswear companies like Nike, Adidas and Puma, with the club pocketing a measly 10-15% of revenue from jersey sales.

The sportswear companies take away the major revenue from sales as they are in charge of manufacturing, distribution and capturing market shares across the world. The football clubs get the global outreach and the sportswear companies get their money.

Everyone hears the statements spreading on social media that a player’s transfer fee was recouped by the club on the first day of jersey sales. This is entirely false, the fact being the club hardly recovers any of the transfer fee outlaid by it.

No, Zlatan Ibrahimovic’s jersey sales did not recoup his wages for Manchester United nor did Ronaldo’s Juventus jersey sales recouped the £105 million paid by the Bianconeri.

Adidas and Nike are ruling the sports apparel industry, and they are canny enough to negotiate a lopsided profit distribution between them and football clubs.

#3: FFP Regulations do not prohibit football clubs from spending a high amount on player transfers

Yes, you read that right. FFP regulations stipulated by UEFA do not ask football clubs to not spend heavily on football players. Rather it says that a club can spend as much as it wants to if it is generating enough revenue over and above what it spends. Simply put, a club can buy a player for £10 billion if it is generating revenue of £10 billion.

Recently, Manchester City found itself in hot waters when UEFA found it breaching the FFP regulations. One might question why did Manchester United not come under questioning when it had spent almost an equal amount as their 'noisy' neighbours.

The answer is that Manchester United earn enough revenue which is greater than what they pay to buy a player. The commercial might the club exercises across the globe, specifically in the Asia Pacific region, enables it to spend heavily on players while recouping the same by earning high revenue.

"Never spend your money before you earn it."

As the saying goes, “Never spend your money before you earn it”, football clubs like Manchester City and PSG should be vigilant to not spend excessive money if they haven’t got the revenue to show for it.

#4: Some football players are not independent and are 'owned' by third parties

The now-disgraced football legend Michel Platini had said that the TPO model (third-party ownership) prevalent in the football industry is 'shameful' and 'a type of slavery' when he was the UEFA president.

The TPO practice is widespread in South American countries like Brazil, Argentina, Chile and Colombia where a football player’s economic rights are owned by companies and organisations. As degrading as it sounds, it is true that these players are bound to their owners, with the owners often dictating where, when and for which club should they play for.

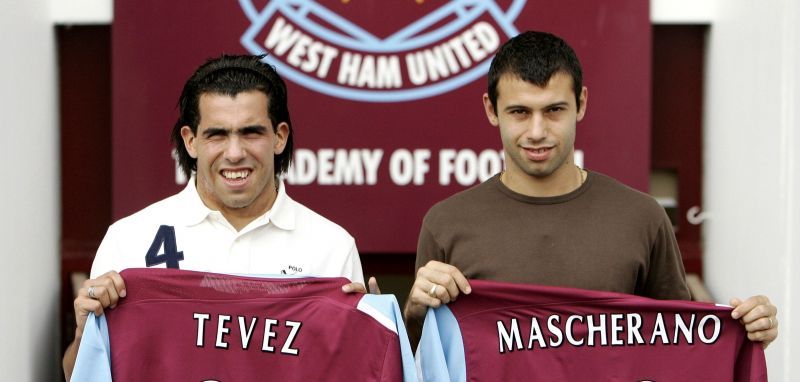

Carlos Tevez and Javier Mascherano are the most famous examples of players owned by third parties when West Ham bought them into the Premier League. Ramires, Hulk and Marcss Rojo are a few of the other examples of TPO-owned players from the South American continent.

This practice has come under the firing line in recent times, and in 2019, football’s governing body FIFA declared a ban on third-party ownership. Although, still in the nascent stage, FIFA has to be vigilant to not let players and third party owners circumvent the rules and continue with the TPO practice.