Celebrating Ronaldo: The greatest World Cup striker of all time

The Wait

“He isn’t a man, he is a herd!”

44 goals in 47 games for Cruzeiro had earned the 17-year-old Ronaldo a call-up to Brazil’s squad for the ’94 World Cup. But for the ultra-cautious Carlos Alberto Parreira, that didn’t mean he would let the buck-toothed teenager play up front. Ronaldo sat on the bench for the duration of the tournament and saw Romário inspire a dull Brazil side to their fourth World Cup title.

The young man, however, came back with something more than just a thrilling experience. He had got his first whiff of the intoxicating allure of the World Cup, that fantastical tournament that would go on to define him as a player, and as a person.

He would spend the next four years – killing time before the next World Cup, it seemed – toying with defenders across Europe. Having joined PSV Eindhoven right after the World Cup, he would go on to score 54 goals in 58 games spread across two seasons for the Dutch giants.

He would then move to Barcelona and in arguably the greatest single season in the long history of the game, he would play 49 games and net a-quite-frankly-ludicrous 47 goals. The next season he would be at Internazionale, this time smashing in 34 in 47.

It wasn’t just the numbers, though; it was the way he did it.

He had everything you could ask for in a striker. There was the ball control and the impossibly fast feet to pull off those ankle-breaking elasticos and ego-bruising nutmegs, the power to bulldoze his way past defenders, the finishing ability that meant he never missed a one-on-one with the goalkeeper.

He was insultingly direct, barreling right at entire defences, throwing them into confusion and slipping through the gaps this created like a thief disappearing into the shadows. His goals were the kind that would have you squealing with delight, the kind of goals that no one else could possibly even have thought of scoring, goals like:

THAT one against Valencia, where he ran through two defenders, shrugging them off like they were insignificant little training cones.

Or THAT one against Compostela, where he gave the non-rugby playing defenders a glimpse of what it must have been to play against Jonah Lomu – taking on the entire defence, and ripping them apart, leaving his own coach (Bobby Robson) holding his head in his hands in sheer disbelief,

Or even THAT one against Lazio, where he sat the goalkeeper down without even touching the damn football.

While there are different versions of what Jorge Valdano reportedly said about Ronaldo, the essence was simple – “He isn’t a man, he is a herd”. He was, and there is quite no other way of putting it, a phenomenon.

O Fenômeno.

Ronaldo was at his unstoppable peak by the time 1998 World Cup rolled into town. Nobody was going to bench him this time. He was the player every teenager kicking a ball wanted to be (including a certain Zlatan Ibrahimovic). He was the one everyone wanted to see, he was the one no-one wanted to play against.

This was going to be his Cup. The wait was finally over.

The Tragedy

"Wait a minute, where's Ronaldo? Mr. Zagallo, are you sure there's no mistake?"

After enduring a slow start in the group games (where he had opened his tally with a splendid half-volley against Morocco), Ronaldo burst into life in the knockout stages – scoring two and setting up one (with a delightful little shimmy) against Chile.

And then, with Philip Cocu hanging off the tail of his jersey – like a man desperately clinging to a speeding train – he scored the goal that pulled the Brazilians level with (arguably) a much superior Dutch side (A Seleção would later win on penalties).

This was the best player in the world, and he was going to make sure his team won. Or so it seemed, until Zagallo submitted his team line-up with just over an hour to go for kick-off before the final, and Ronaldo’s name was nowhere to be seen.

The FIFA representative, whose job it was to collect the team sheets, couldn’t quite believe his eyes. Ronaldo had suffered a convulsive fit the night before, and the doctors didn’t think he was fit to play. But somehow, with confusion reigning, Zagallo thought it best that he play him, and put him back in the starting XI

It was a mistake.

A Zinedine Zidane-inspired France would wallop the Seleção 3-0. Ronaldo was a shadow of himself, wandering around the Parc des Princes like a lost puppy. His presence for once had made his team weaker.

Even the most hard-hearted of men must surely have felt a lump in his throat watching the 21-year-old boy wonder looking as despondent and disconsolate as that.

Tragedy, though, has a manner of piling up in the most unexpected, unwelcome manner. In a match against Lecce the following season, Ronaldo’s knee (the same one that had seen him spend half a season on the sidelines at PSV) buckled. A comeback six months later was cut short when 7 minutes in, the knee gave way again.

He would play a grand total of 17 games in the three years leading up to the 2002 World Cup.

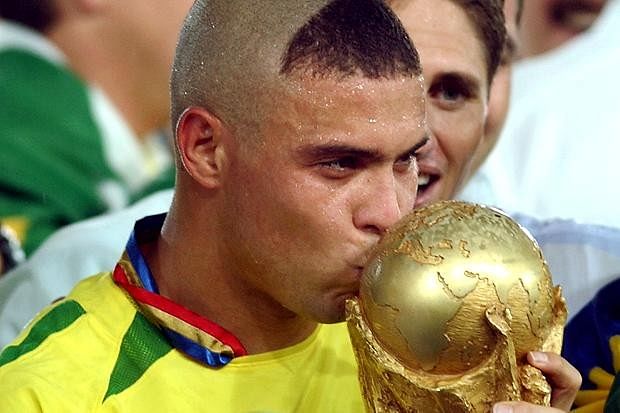

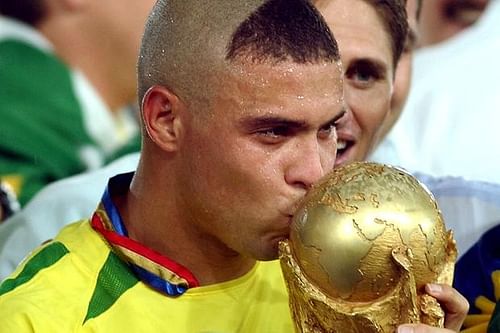

The Redemption

"This gives hope to everyone who is injured; even those who aren't sportsmen, to see that by fighting you can make it.”

He wasn’t supposed to be in the team. He had missed the entire qualification campaign, and everything in between. He had barely had a kick. The doctors had been saying it would be lucky if he could ever walk properly again.

Yet there he was, flying on to a cross to prod in a wonderful effort that drew Brazil level in their opening match against Turkey. The arms-outstretched-Antonov-winged celebration had been replaced with an almost insouciant wag of the finger.

But much of what had made him the most frighteningly brilliant player on the planet remained – the odd burst of explosiveness, the Velcro touch, the blunt directness and that unnerving calmness under pressure.

He scored in every game except the quarterfinal against England, including the lone goal in the semifinal and the two that took Brazil past the redoubtable Oliver Kahn and his obdurate Germans. They were good goals too: the toe-poke against Turkey; the tap-in that was the opening goal in the final; and that expertly taken whip into the corner that sealed the deal.

But this time, it wasn’t the manner of the goals that mattered.

It was miraculous that he had it made it to the tournament in the first place. The fact that he scored the goals that won Brazil the Cup, emerging with the Golden Boot at the end of it all, stretched the definition of impossible.

Like Gérard Saillant, the French surgeon who operated on the Brazilian’s knee said, this gave hope to everyone. This triumph was not one of pure footballing skill, but that of an incredible, underrated mental strength.

Ronaldo had shown incredible strength of character to come back from the brink of oblivion and snatch the glory that was so rightfully his, the triumph that had eluded him in such a heart-breaking manner just four years past.

Redemption was his.

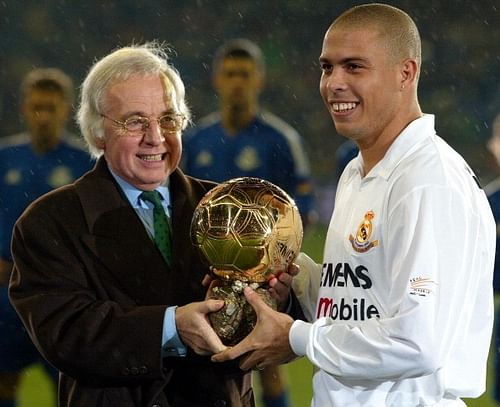

The Record

“You run! I don’t. I score goals.”

After the heady success of the World Cup, Real Madrid came a-calling, and in his first season he (along with the great Iker Casillas) inspired a pretty average Madrid side to the league title. Yet he wasn’t quite the player he used to be.

The player who would take on entire teams with runs from the halfway line, full of body feints and stepovers at insanely high speed, turned slowly, gradually, naturally into an altogether traditional goal poacher, who couldn’t be bothered to do anything other than score goals.

Like he told a newcomer to the team who had shouted at him for not running hard enough – “You run! I don’t. I score goals.” (As the incident goes, five minutes later, he did score. And then offered a typically cheeky “That okay by you?” by way of repartee).

He had adapted to the loss of the old frightening explosiveness by becoming more of a goal poacher, but there was no doubt that he was on the decline. By the time the 2006 World Cup came about, it would have been hard for the neutral observer to differentiate between Ronaldo-the-footballer and Ronaldo-the-caricature.

Fat (there really is no other way of putting it), unfit and generally the butt of jokes, Ronaldo was a controversial inclusion in the Brazil side. He did score though, his target very clear – the record for the highest goalscorer in World Cup history.

A header against Japan got him on level terms with Just Fontaine; a wonderful whipped effort later in the same match saw him tie the legendary Gerd Muller. And then came a typical Ronaldo effort against Ghana.

Bursting onto a perfect through ball from Kaka, the great man did one of his legendary step-overs – not the wishy-washy kind you see kids do these days; a Ronaldo step-over involved the entire upper body moving along with the foot – and sat the keeper on his backside. The stepover wasn’t a trick for the tricks sake, this was a weapon, and no one knew how to use it better.

And then, as he had been doing since he was a kid, and like no one else before or since has done, Ronaldo Luís Nazário de Lima walked the ball into the net.

The record was his.

With all due respect to the one extra goal that the exceptional Miroslav Klose has, the title of “Best Striker in World Cup history” firmly belongs to the man whose life was intertwined with the tournament in a fairytale of epic proportions. To the man they called O Fenômeno.